- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

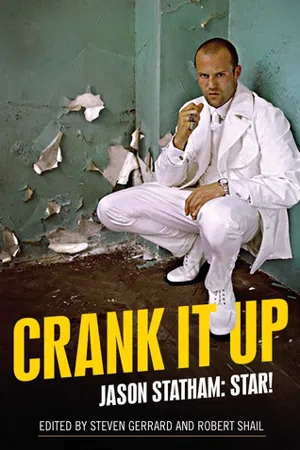

Jason Statham has risen from street seller through championship diving and modelling to become arguably the biggest British male film star of the twenty-first century. This is the first book to offer a critical analysis of his work across a variety of media, including film, television, video games and music videos. Each chapter focuses on a particular aspect of Statham's career, from his distinctive screen presence to his style, branding and celebrity. Accessibly written, and featuring a contribution from Hollywood director Paul Feig, who worked with Statham on the 2015 action-comedy Spy, the collection will appeal to a wide audience of scholars, students and fans.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Crank it up by Steven Gerrard,Robert Shail, Steven Gerrard, Robert Shail in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Statham and (reframing) masculinity

1

Reframing the British tough guy: Jason Statham as postmodern hero

Robert Shail

The tough guy, in one form or another, has been a staple of popular narrative cinema since its beginnings and in particular has been central to key genres such as the gangster film, the western or the contemporary action movie. In his influential study Stars, Richard Dyer (drawing on the work of sociologist O. E. Klapp) lists the Tough Guy as one of three dominant star types, along with the Good Joe and the Rebel (Dyer 1998: 48–51). Dyer’s definition of the Tough Guy borrows from Klapp’s original notion of a deteriorated hero but refines it in a more sympathetic way to understand its audience appeal. For Dyer, the Tough Guy is differentiated from the hero or Good Joe by a level of moral ambivalence or ambiguity: ‘he confuses the boundaries between good and bad behaviour, presses the anti-social into the service of the social and vice versa’ (1998: 49). At heart, Dyer’s Tough Guy serves the moral certainties of the wider society like the hero but his actions, and the type is identified as male, often utilise methods that are anathema to a Good Joe. In straying across the ethical lines to employ the anti-social in the aid of social, the Tough Guy becomes a morally ambivalent figure. But this is also where his appeal to an audience lies. Whereas the certainties of the Good Joe may be alienating to parts of the audience who feel their own inadequacies heightened in comparison with this hero, the Tough Guy represents a figure as flawed as they are, someone who tries to do the right thing and gets there in the end but who may lose his moral compass along the way. This is the appeal of Robert Mitchum as opposed to John Wayne or Bruce Willis rather than Kevin Costner.

The example Dyer gives is James Cagney in his many gangster roles for Warner Brothers from the 1930s. Cagney’s persona provided audience excitement and wish fulfilment through his personal dynamism and unfettered ambition but he remains sympathetic despite his capacity for violence. His socially deprived childhood is often sketched in, so that we feel we understand his motivations, as in The Public Enemy (1931), or in the final reel where he is redeemed by an apparent act of selflessness, as per Angels with Dirty Faces (1938). Audience identification is encouraged despite the moral contradictions of siding with characters on the wrong side of the law, an ambivalence usually corrected by final reel punishment. Another controversial example that illustrates the type and its appeal would be Clint Eastwood in Dirty Harry (1971), where the maverick policeman retains the legitimacy of a personal code of conduct but stretches the methods used in its service to such extremes as to divide audiences between those who still find Harry both human and sympathetic and those who see a justification for a near fascist use of violence. Harry’s moral code gives him the ethical high ground, while his confusion at the corruption all around him is expressed by his finally tossing aside his police badge, mirroring Gary Cooper’s actions at the close of High Noon (1952). An additional characteristic that Dyer attributes to the Tough Guy is a specific ability to reflect wider societal anxieties especially in relation to masculinity and violence. These can come to the surface at particular historical moments of collective stress, such as the depression of the 1930s or the political turmoil of 1970s America at the time of the Vietnam War.

The progression of the tough guy in American cinema might usefully be charted from the popular gangster films of the 1930s, through the patriotism of the Second World War, to the post-war pessimism of film noir, and onwards into the crime movies of the 1960s and 1970s, taking in the varying fortunes of the western genre along the way. The prominence of the tough guy in a wave of apparently recidivist action movies in the 1980s attracted considerable scrutiny from feminist scholars. This work was prompted by the popularity of stars such as Arnold Schwarzenegger, Bruce Willis and Sylvester Stallone appearing in a succession of box office successes such as the Terminator, Die Hard and Rambo franchises, along with the continuing popularity of Eastwood (Dirty Harry became the subject of his own franchise). In the work of Yvonne Tasker and Susan Jeffords, the rise of these ultra-masculine stars is often read as a response to the aggressive foreign policy and free market politics of the Reagan administration, as well as to a male backlash against the perceived influence of Second Wave Feminism in the wider society. The emphasis on polished muscularity and male bonding in these films has also been interpreted in relation to discourses of fetishised power or sublimated homoerotic undercurrents. In Spectacular Bodies: Gender, Genre and the Action Cinema, Tasker debates whether this re-emergence signalled an attempt to reassert male hegemony at a point when it appeared to be under threat, or whether it just indicated its final death throes (Tasker 1993: 109–131). Jeffords takes a similar approach in her ironically titled essay ‘Can Masculinity be Terminated?’ (1993). The recent success of Jason Statham in the new millennium suggests that this form of cinematic masculinity proved more resilient than might have been predicted in the post-Reagan 1990s. The purpose of this chapter is to explore how Statham’s particular version of the Tough Guy has negotiated this era and found new ways of successfully mutating.

Dyer’s approach occasionally tends towards the broad-brush and often uses Hollywood as a paradigm for its exemplars. Work by scholars within British cinema history such as Bruce Babington (2001) and Andrew Spicer (2001) has suggested that while the concept of a star typology is useful, its exact application needs to integrate a sensitivity to place as well as time. For Babington, ‘whatever stars mean in the larger cinema, they signify more complexly in relation to their original environment’ (Babington 2001: 22), allowing for the analysis of representational characteristics such as gender, class, ethnicity and national identity. Spicer’s study of British male stars, Typical Men, fractures and extends Dyer’s approach across a number of types which allow the nuances of post-war Britain to be explored over a period of time, charting how the various British types fluctuate and evolve in response to changing social conditions and audience demands. This is a useful construction when considering how Jason Statham’s star persona, rooted as it is in a British working-class context, has extended the Tough Guy type in recent years.

Although Statham’s career has established him as a key supporting performer and emerging lead actor in major Hollywood films, his early career and star persona remain grounded in British culture. He was born in Shirebrook, Derbyshire in 1967 and grew up in Great Yarmouth in a working-class family. His early career success was as an athlete, which then led to modelling and appearances in music videos, supplemented by occasional work as a street seller like his father. His breakthrough film role in Guy Ritchie’s Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels (1998) immediately established his public image, one in which a working-class, specifically London-centred persona was fundamental to his appeal. Even later Hollywood films such as The Expendables (2010) or Spy (2015) continued to play on Statham’s established persona and assume the audience’s acceptance of his British working-class background in a manner previously established in the 1960s by stars such as Michael Caine, Terence Stamp and Sean Connery. In order to assess Statham’s particular modification of the British working-class tough guy, it is helpful to trace this specific ‘type’, in Dyer’s terms, back to its starting point in the late 1950s.

Andrew Spicer suggests that the first British actor to ‘forge a consistent persona as the modern tough guy was Stanley Baker’ (Spicer 2001: 73). Baker had impeccable working-class credentials as the son of a coal miner from Ferndale in South Wales. After years of taking bit-parts on stage and in British films, alongside some greater success on British television, Baker made his commercial breakthrough with the American director Cy Endfield’s Hell Drivers (1957), in which his typical star persona is first seen. Baker’s British tough guy is an ex-convict trying to go straight. He is certainly brave, resilient and physically strong but he also projects a tenderness in his friendships and restraint in his use of violence which mark him out; he only finally resorts to using his fists after continuous goading by the mildly psychotic Red, played by Patrick McGoohan. His subsequent roles in Blind Date (1959), Hell is a City (1960), The Criminal (1960) and A Prize of Arms (1962) further developed the character, whether as policeman or criminal, making him one of the most popular British actors with domestic audiences in the period. His persona combined aspects of the established American tough guy such as Robert Mitchum, unusually for a British star at the time (he did much of his best work for two expatriate American directors – Cy Endfield and Joseph Losey), alongside a soulfulness frequently attributed to his Welsh background, and a keen sense of class resentment (Shail 2008: 50–52). Baker’s tough guy also suited the times: ‘the new image that he offered to audiences, as a working-class hero with scant respect for authority, chimed perfectly with a transformation that was taking place in Britain itself’ (Shail 2008: 62).

Spicer traces the fate of the British tough guy through to the turn of the millennium. He notes the motif of class identity, as well as the impact of challenges to traditional notions of masculinity brought about the wider discourses of feminism and changes in work patterns for men, particularly the decline of working-class employment in the manufacturing industry. He points to an ongoing preoccupation with crime as an outlet for social unease, the focus on rebellion or alienation, and a growing escalation in violence. These features can, nonetheless, be seen as negotiating tropes evident in Baker’s persona. A newer characteristic for Spicer is the appearance of a ‘damaged’ masculinity whereby the working-class tough guy frequently appears as a figure so misshapen by the social upheavals of the last forty years that he has mutated into a dysfunctional relic, as portrayed by actors such as Christopher Ecclestone, David Thewlis, Gary Oldman, Tim Roth and Ray Winstone (Spicer 2001: 195–198). It was just at a point where this trend seemed to have potentially exhausted itself that Jason Statham emerged into British cinema stardom.

The typical characterisation offered by Statham in Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels and Guy Ritchie’s second successful foray into Britain’s crime underbelly, Snatch (2000), is markedly different from anything to be found in Baker’s films, or even those of Michael Caine or Ray Winstone. The films adopt an irreverent and deliberately ironic attitude to the more familiar generic elements of the crime genre and the tough guy type. It’s not stretching credibility too far to suggest that many of the devices employed by Ritchie in his framing of Statham’s performances are essentially postmodern in their approach. Susan Hayward’s description of the four elements that define postmodernism in cinema are a helpful measure here (Hayward 2000: 277–279). She lists these as simulation, prefabrication, intertextuality and bricolage. Prefabrication refers to the knowing use of many existing motifs taken from the rich past of cinema history, while intertextuality denotes the referencing of other cultural sources from outside of cinema (and particularly from other forms of popular media). Bricolage is a means of assembling these apparently disparate elements in ways that emphasise their collision or which juxtapositions them in unexpected ways. Simulation is a term that unites the other three elements and gives postmodernism its central mode of address, which for Hayward lies in the use of either parody or pastiche. Ritchie’s films make abundant use of all these techniques and reflect them through the performances of actors like Statham.

Statham’s career has gone on to incorporate these postmodern characteristics repeatedly, whether evidenced by the number of remakes he has appeared in – Mean ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Figures

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Epigraph

- Introduction

- Part I Statham and (reframing) masculinity

- Part II Statham and genre case studies

- Part III Rebranding Statham

- Conclusion

- Select bibliography

- Jason Statham filmography

- Index