![]()

1

Frank Ferguson and Danni GloverScottish revenants

Scottish revenants: Caledonian fatality in Thomas Percy’s Reliques

Thomas Percy’s The Reliques of Ancient English Poetry, first published in 1765, was a seminal text in English literature.1 A comprehensive three-volume set of British ballads, it was one of the most significant collections of the century, and its influence was felt on British editors and writers for generations afterwards. The backdrop for this literary endeavour was a culture war in English and Scottish literature which was part of the long-standing antagonism between the two nations. This antipathy had escalated after the Glorious Revolution and subsequent Union and found expression in a variety of texts. At the core of this battle was a struggle for cultural superiority between Scotland and England.2 The Reliques superficially championed all anglophone British balladry, but in reality it demarcated profound cultural differences between English and Scottish peoples, history and mentalities. While its mission ostensibly sought to celebrate the heroic balladry of the British Isles from Gothic antiquity onwards, it did so by implicitly and explicitly depicting the Scottish psyche, particularly that of its nobility, as so prone to bellicosity as to be tantamount to being suicidal.

The mission of the collection was born from profound cultural antagonism, which manifested itself in many disciplines and encompassed interpretations of national language, literature, history, philosophy and economics. One of the major concerns of the Reliques was to discover literary origins and early practitioners so as to assert the cultural, literary and political supremacy of England over Scotland. By doing so, proponents could then lay claim to cultural and thereby moral precedence and superiority over their rivals. In the early 1760s, this hunger to defend and promote Englishness had been given impetus by the publication of the alleged works of Ossian. With the discovery of the alleged translations of Ossian by James Macpherson in 1759, it was felt by many that Scotland had scored a decisive victory over the English in reclaiming an ancient Homeric poetic figure. Not only did Scotland have an ancient oral tradition in the Highlands, but Macpherson had the ability to fashion Ossian in a manner very attractive to a contemporary audience, replete with all the trappings of mid-century sensibility framed in a Celtic twilight as lachrymose as any Wertherian landscape. Death-haunted and dying in the mists of the Caledonian dusk as Ossian and his fellow bards may have been, their elegiac paeans did much to resuscitate the standing of Scotland’s ancient nobles whose reputation had perished in the ignominy of Culloden. This revenant of sentimental Jacobitism returned as a spectral poetic genius of the first order and posed many problems for his critics, who sought to discredit the success of Macpherson by claiming his work was plagiarised and not authentic.

Percy’s response to Ossian and Scotland in general in his Reliques was to deploy a Gothic riposte in two approaches. First, in a historiographical sense, he posited a conception of British literary history which maintained that the English were cultural inheritors of the Goths, a racial grouping which he believed was superior and different to Scotland’s antecedents, the Celts. He was not alone in this belief and drew on the ideas of Nathaniel Bacon and Jonathan Swift who had identified political, legal and cultural similarities between contemporary English society and the Goths several decades previously. By advancing this idea, Percy was aiming to defend and consolidate a cultural position that favoured an interpretation of English predominance over other constituent members of the United Kingdom. This was ultimately an antiquarian response, basing his argument on having literary artefacts in the shape of manuscripts and items which proved the facts of his claims against what he believed were the spurious assertions made by proponents of oral evidence. This evidence he termed ‘reliques’, borrowing the quasi-religious terminology to add an extra frisson of meaning to his canon-building mission.

Secondly, he adopted Gothic literary approaches in his treatment of Scotland as a nation which, rather than being labile and imbued with sensibility, is violent, fraught and haunted to the point of terrorising itself – practically a suicidal nation. If the Ossianic poetry is a lament for the human subject caught in the predicament of age and death, the Reliques determines a judgement on Scotland that it is an unstable, barbarous place which precipitates self-slaughter. Though aimed as a unifying text between the constituent nations of Great Britain, the Reliques insists on Scotland as a dangerous, if minor, doppelgänger of England – a nominal national space which exists in Britain’s past and in the eternal moment of its own death. By comparison, England and Englishness is determined as the dominant cultural force in the Union, and even when English suicides are discussed they are seen as an act of romantic sentimentalism – a by-product of overweening love and sensibility rather than the effects of an alleged rapacious Caledonian national character. Ancient and contemporary ballads, in Percy’s often unsteady editorial stewardship, were reimagined as components of a Gothic metanarrative of British literary history and canonicity. His collection comprehends English and Scottish histories as a contrast between sentimental tragi-comedy on the one hand and a pathology of the nation on the other. This anthologising process employs an implicit classification of the act of suicide in each nation to affirm the respective character of England and Scotland and to valorise Percy’s pro-English Gothic interpretation.

Susan Stewart wrote, ‘In order to awaken the dead, the antiquarian must first manage to kill them.’3 In Percy’s case, the insinuation is that the subjects in many of the songs and ballads he assembled had helped in this process by dispatching themselves in the first place. What are left behind are textual artefacts and objects on which, much like a coroner, the antiquarian editor must conduct a form of literary post-mortem. Despite his calling as an Anglican clergyman, Percy did not necessarily follow a discussion of his protagonists with a moralising of the deceased. This has less to do with a relaxation of such practices in the eighteenth century as it has with the more pressing moral and cultural points to be made in his editing. Certain statements made in the text would corroborate that Percy was aligning himself with trends in the discourse of suicide in the eighteenth century as one that was moving away from perceiving suicide as a sin towards understanding it more as a process of mental illness.4 Instead, the texts which he edited allowed him to inter their remains within an intricately constructed Gothic reliquary.

To comprehend why Percy’s work is ‘Gothic’ in its intent, it is necessary to briefly introduce his text. Ostensibly, the collection sought to publish a series of English and Scottish ballads. Percy spent a considerable amount of time creating eclectic texts of the various poems he would print, often collaborating with other literary experts. Furthermore, these poems were placed within a very complex system of headnotes, footnotes, glosses, notes, essays and illustrations. If the poems were the relics, then the editorial scaffolding around the poems was the reliquary that housed them and was a vital factor in the success of the whole collection. Without Percy’s specific editorial techniques, the collection would not have benefited from the popularity it enjoyed during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. He may not have been a great innovator in the field of editorial collection, but the extent of his interpolation sets him apart from previous and contemporary editors. The majority of editors before Percy were concerned, as in Edward Capell’s Prolusions (1760), to include as few additional notes as possible so as to keep ‘the beauty of the page’.5 Or, as in the Collection of Old Ballads (1723–25), an attempt was made to propitiate the book’s audience for offering them such a low-status genre as the ballad, when the anonymous editor apologises, ‘I never pretended to give him anything more than an old song.’6 Percy provided an enormous amount of information around the poems that drew considerable consternation from advisors such as William Shenstone, who believed the poems should stand without introduction. Thus the Reliques appeared to be as much an academic or, in eighteenth-century terms, a ‘philosophical’ treatment of English song and balladry, approaching the scholarship of Thomas Warton’s History of English Poetry in its scope and erudition.7

The presentation of the collection is of paramount importance, and an inspection of this aspect of the Reliques demonstrates how Percy attempted to deal with his materials. In addition, the prominence of the word ‘English’ in the title demonstrated his willingness to turn his collection into a nationalistic endeavour and tap into contemporary appetites for and anxieties about the state of his national culture. This ran parallel to his desire to turn the ballads into art objects. The collection was presented to readers in such a way as to try and convince them they were viewing national literary heritage. If the Reliques functioned as a museum of English literature, then Percy was the curator, guiding, informing and instructing his audience through unknown aesthetic possibilities. In comparison to Macpherson’s Fragments, the production values of the Reliques were much higher. Percy’s agenda to transform the ballads into national literary heritage was underlined throughout the various material levels of the anthology. The sense of materiality, indeed the corporeality, of the Reliques was emphasised due to the supposedly core texts being derived from a rescued manuscript of some years previous:

This very curious old Manuscript in its present mutilated state, but unbound and sadly torn &c., I rescued from destruction, and begged at the hands of my worthy friend Humphrey Pitt Esq., then living at Shriffnal in Shropshire, afterwards of Priorslee, near that town; who died very lately at Bath (viz. in summer 1769). I saw it lying dirty on the floor under a Bureau in ye parlour: being used by the maids to light the fires.8

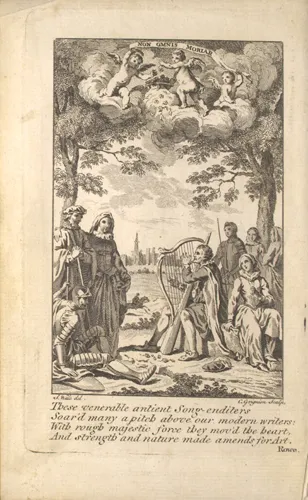

The frontispiece and title page of the Reliques provide a very important visual key to the whole collection. Percy had declared that the frontispiece should be ‘in the Gothic style, no classical Apollo, but an old English Minstrel with his harp’.9 This image was used to portray many of the objectives of the Reliques. It provided a snapshot of the stylised medieval world of knights and ladies transfixed by the song of a minstrel. The print showed medieval ‘English’ costumes, not the classical paraphernalia of Southern Europe, in an effort to demonstrate that art and high culture could be found as readily in an English setting. The minstrel was prominent in the foreground of the print, just as Percy would argue his social status demanded as an inheritor of the mantle of ancient bards. Just like the bards before him, he was a poet historian, a man of feeling, insight and sensitivity during an otherwise barbaric age.

1.1 The frontispiece of the Reliques.

This image is juxtaposed with the title and a second illustration on the recto page. Under the full title, a scroll or manuscript is placed with a harp in a ruined Gothic arch surrounded by ancient trees. All is in ruins. The ruin motifs of sentimental medievalism appear to have replaced the once vibrant medieval world of the verso page. The only thing that is left intact is the manuscript, and with that goes the implication that only a learned editor like Percy can guide the uninitiated back to past glories, for only he has the skill, knowledge and insight to decipher the text. The mottoes on both pages link to suggest this: ‘non omnis moriar’ (verso, ‘not everything decays, perishes’) because ‘durat opus vatum’ (recto, ‘the work of the poets/bards/prophets endures, lives’). In the combination of these two images, Percy celebrates and compartmentalises the past. He opens up the possibility of glimpsing English history in all its imagined ceremony, and lame...