- 424 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Länder and German federalism

About this book

An illuminating introduction to how the Lander (the sixteen states of Germany) function not only within the country itself but also within the wider context of European political affairs. Looks at the Lnader in the constitutional order of the country, and the political and administrative system. Their organization and administration is fully covered, as is their financial administration. The role of parties and elections in the Lander is looked at, and the importance of their parliaments. The first work in the English language that considers the Lander in this depth.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Länder and German federalism by Arthur Gunlicks,Christopher Duggan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1

The origins of

the Länder

Introduction

Where is Germany? What are its constituent parts? Who is a German? These questions may not be entirely unique to Germans; they are sometimes asked in many nation-states in Europe and elsewhere. But questions about identity have been asked for centuries in Germany and to some extent are still asked today. For hundreds of years “Germany” was a group of tribes located in north-central Europe, most but not all of which became a part of the empire of Charlemagne and, after the death of Charlemagne, a part of what would become the Holy Roman Empire. This empire consisted of hundreds of political units of widely varying sizes and shapes, including noncontiguous territories, speaking different dialects and developing different cultures, headed by kings, princes, dukes, counts, bishops, and various and assorted minor nobility generally referred to as knights. Those who lived within the borders of the empire were not all Germans by today’s standards, but most were even if they did not know it. For in the middle ages, people did not think in terms of nationality. They were the parochial subjects, not citizens, of a prince or lord, and nationality was not a meaningful concept for them.

Later, in the sixteenth century, they became divided also by religion. This and other divisions led to a devastating Thirty Years’ War (1618–48) between Protestants and Catholics, both German and foreign, on German territory. For many decades this had far reaching negative effects on the economic, cultural, and political development of Germany. The Holy Roman Empire, not a “state” but a historically unique league of princes with some confederate features, was naturally weakened by the Thirty Years’ War and other conflicts between and among the princes, but it continued to exist in some form until Napoleon forced its dissolution in 1806. One important change between the Thirty Years’ War and 1806, however, was the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648 which, among other things, is generally credited with having introduced the modern concept of the state. Subjects were now more likely to identify themselves as Bavarians, Württemberger, Hanoveranians, Saxons, and so forth.

Following the French Revolution, the concept of the state was modified to include a particular kind of state: the nation-state. This meant that it was now the goal of people who identified with one another – whether because of geography, language, religion, history, or culture – to form a state which included this distinct group of people. This led to the rise of nationalism, which generally replaced religion as the major focus of common identity. Napoleon had manipulated national feelings to great personal advantage, and the monarchical heads of state in the German and Austrian territories had good reason to fear the consequences of nationalism in their own highly divided and fragmented states.1

In 1815, with the final defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo, the German Confederation of thirty-nine states, including Austria, was formed. It was a very loose confederation, the main purpose of which was to provide internal and external security. This confederation, supplemented by a Customs Union of 1834, which excluded Austria, continued to limp along until 1866, when the two major German states, Prussia and Austria, fought a brief war that led to their final separation within even as loose an arrangement as the German Confederation. In 1867 more than twenty German states joined in the formation of the North German Federation, led and dominated by Prussia. Following a brief war in 1870 between France and Prussia, the states in the North German Federation and the four separate and independent South German states joined to form a united German state for the first time in history.

But the questions of where Germany is and who is German were not resolved. The German population in Austria and the majority German population in Switzerland did not become a part of the new German state. Then, following defeat in the First World War, many Germans who had been a part of the Kaiserreich were now in France or Poland, and even more Germans who had been a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire were now in various, mostly newly created, separate countries, such as Czechoslovakia, Italy, and Romania. These developments fed nationalistic fervor among many Germans, with the result that the most radical nationalistic elements under the leadership of Adolf Hitler and his National Socialist Party were able to capture the German state and launch a war to unite all Germans and expand German territory in the East at the expense of the peoples living there. They also, of course, led to the Holocaust and other crimes against any and all opponents of Nazi rule.

Following the Second World War, the questions arose again. Where is a Germany that has lost one-fourth of its pre-war territory and many former citizens to Poland and the Soviet Union, has had to absorb as many as 12 million refugees and expellees, is divided first among the four Allies into four zones and then into two hostile camps facing each other throughout the Cold War, and then is presented suddenly and unexpectedly with the opportunity to unite in peace? This latest unification seems to have answered once and for all the question of where Germany is if not in every case who is German. But now Germany is faced with two other questions that are new to the post-war era: where and how does Germany, and, for that matter, where do the other European states, fit into an increasingly integrated Europe? And, less dramatically but still of considerable importance, where and how do the current German states (Länder) fit into a united Germany? Are there too many of these Länder? Should they be joined in ways that would reduce their number from sixteen to perhaps eight or ten? Would the predicted economic and administrative benefits outweigh the potential costs in loss of traditions and regional identity? Is there a strong German identity that is shared between former East and West Germany in spite of forty years of experiences with profoundly different regimes?

This chapter and this book cannot answer all of these questions satisfactorily, but they can help to provide some background and a framework for understanding how Germany and the Germans literally have come to where they are today. The focus, then, will be less on the larger issues of German identity over the past decades and more on the sources of identity of the people within Germany for the regions in which they live today.

The Holy Roman Empire

Following Charlemagne’s death, the Treaty of Verdun in 843 divided his “Roman Empire” into three parts: the West Frankish Kingdom, the Middle Kingdom, and the East Frankish Kingdom. The West Kingdom would become the core of France, the East Kingdom the core of Germany. The Middle Kingdom would become the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and areas later contested by France and Germany, such as Alsace-Lorraine and the west bank of the Rhine. There were five “stem duchies” (Stammesherzogtümer) in the East and Middle Kingdoms, based originally on Germanic tribes (Saxony, Franconia, Swabia, Bavaria, and Lorraine – which included the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg on today’s map). They did not, however, prove to be durable territories. Election of kings by the nobility in the Carolingian Empire was a Germanic influence that complemented the Roman administrative institutions adapted to the local conditions. This meant that the king was more primus unter pares, and that the kingdom represented a central authority versus particularistic tendencies.2 The empire followed this tradition of election in the selection of emperors by the stem dukes before the tenth century and again after the beginning of the thirteenth century.

By “the middle of the eleventh century the realm was firmly united under its ruling dynasty and all traces of particularism seemed on the point of disappearance.” 3 The emperors gained power at the expense of the duchies by dividing territories, for example, the emergence of an important part of Austria from eastern Bavaria in 1156, and by using their authority to appoint the high clergy whose administration competed with that of the dukes. Nevertheless, the tendency was for the Reich to divide into smaller units of rule, so that while the stem duchies disappeared, smaller territorial duchies and territories led by the “princes” emerged in their place. These smaller territories provided the actual government over their subjects, but the rulers were not sovereign and enjoyed their power only as a part of the Reich and in alliance with the emperor.4

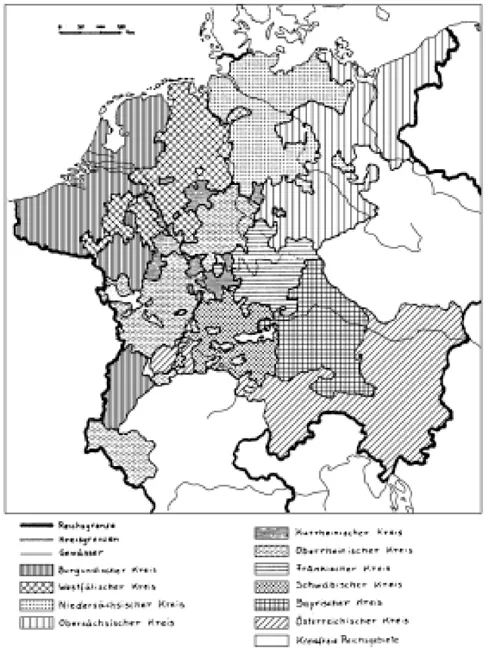

The emperor ruled through the princes, who in turn ruled through the lesser nobility, such as the knights. In the imperial free cities small groups of oligarchs, usually from the guilds, were in charge. There was no capital city of the Reich, and the emperor traveled from place to place with his entourage to demonstrate his authority. His territorial base consisted of his own lands.5 Only in these territories did the emperor rule directly. While the princes of the realm were not sovereign, they did enjoy considerable autonomy (Landeshoheit). The empire served to protect the smaller territories from annexation by their more powerful neighbors, and it provided some protection from outside threats to their territorial integrity. The nobility was based on heredity, but that, of course, did not apply to the ecclesiastical princes. In the early centuries the emperor appointed them and used them for purposes of administration. He also received the moveable inheritance of the bishops and other revenues. In return, the Church received various lands, customs duties, and other benefits. In the twelfth century the emperor relinquished his right to appoint archbishops, but his presence at their election still gave him considerable potential influence (map 1.1).6

Map 1.1 Germany in the sixteenth century

At this time the controversies over the appointment of the Pope, whose power and actions had weakened the empire, led to a strengthening of the territorial princes at the expense of the emperor.7 The princes were also strengthened by the reestablishment in 1198 of the traditions of electing the emperor. Election of the emperor was confirmed by the Golden Bull of 1356, which gave the right of selection to three ecclesiastical and four secular princes (Kurfürsten) and broke the bonds of papal subjugation.8 But the rejection of an hereditary emperor also weakened the empire, b...

Table of contents

- Cover page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of maps, figures, and tables

- Preface

- A note on terminology

- Introduction

- 1 The origins of the Länder

- 2 Theory and constitutional framework of federalism

- 3 Administrative structures in Germany

- 4 The Land constitutions

- 5 Financing the federal system

- 6 The German Land parliaments (Landtage)

- 7 The Land parliament deputies in Germany

- 8 Parties and politics in the Länder

- 9 Elections in the Länder

- 10 The Länder, the Bundesrat, and the legislative process in Germany and Europe

- 11 European and foreign policy of the Länder

- 12 Conclusion: the German model of federalism

- Index