![]() Part I

Part I

Discourses of sustainability![]()

1

The millers’ tales: sustainability, the arts and the watermill

Jayne Elisabeth Archer, Howard Thomas and Richard Marggraf Turley

In 2009, the Nobel Prize-winning economists Joseph E. Stiglitz and Amartya Sen issued a report urging a shift from a purely economic analysis of a country's success or relative failure to one which includes (and is informed by) an analysis of wellbeing and sustainability (Stiglitz et al. 2009). The report concluded that wellbeing and sustainability, which comprise factors such as culture, education, health, water security and food production, are intimately linked. Although their terminology and modes of communication may have differed, the artists and writers of the past have also been attuned to this connection – a connection many of us today have almost lost – and to the various pressures that have threatened to undo it.

The watermill in time

An important but often neglected site in the relationship between literature and the visual arts on the one hand, and sustainability on the other, is the watermill. Our concern here is with the water-driven mill, while we acknowledge there is also a tale to be told about windmills. Wind is a fickle source of power, as opponents of modern wind farms like to point out. Water, by contrast, is seemingly more controllable and predictable – in this sense, more sustainable – than wind, and therefore a more stable centrepiece of community life throughout the world and history. The watermill is frequently sentimentalised as what Terry S. Reynolds has called a ‘picturesque artifact’ in the modern mind, and abstracted from specific historical moments and social forces (Reynolds 1983: n. pag.). For many hundreds of years the watermill was the point at which food entered most transparently and immediately into the worlds of politics, governance, culture and social justice. It was a complex site within which communities were created and negotiated, through cultural as well as material relationships. The importance and intricacy of the work performed in and by the watermill elevated it to symbol, ritual, myth and mystery. But, for as long as it remained an everyday part of town and village life, it was also an insistent and shaping material presence. The skilled miller, sifting through the grain, was an important guard against the corruption of the food chain by toxic agents such as darnel and ergot (Archer et al. 2014). The watermill made it possible for the owners of smallholdings to work their land and feed themselves. In it, the ongoing conflict between country and city, and their very different appetites, was played out. It was a place of urgency and contention, in which weights and measures – customary and standardised – were debated and resisted. In short, the watermill had an essential role in the formation of pre- and early modern communities: it enabled them to be self-sustaining; it made the people and their land sustainable.

There are several rich accounts of the history of the watermill in Britain – for example by Reynolds (1983), Steven S. Kaplan (1984) and Martin Watts (2006) – and Beryl Rowland (1969, 1970) has surveyed literary (including classical) representations of milling and millstones. Reynolds suggests that its very ubiquity in history and literature has made the watermill an overlooked subject for contemporary cultural and ecocritical study (1983: 3). This desertion perhaps also results from the fact that for much of British history (and English literary history), the physical structure of the watermill itself appeared resistant to change: in the period 1300–1850, the basic machinery and processes used in the watermill remained much the same (Reynolds 1983: 3). We see the unquestioning acceptance of traditional custom and practice in the lack of a definitive answer to, or even curiosity about, whether and to what degree overshot waterwheels deliver more power than undershot. It was not until 1759 that the engineer John Smeaton (builder of the Eddystone Lighthouse) finally resolved the matter in a paper to the Royal Society. As a result of experimental and mathematical modelling – among the earliest examples of the application of scientific method to engineering – Smeaton showed conclusively that the overshot wheel is twice as efficient as the corresponding undershot wheel (Capecchi 2013).

It's a familiar story: scientific insight and technological advance that lead to first gradual, then rapid, sweeping away of ‘inefficient’ tradition and, with it, of hitherto homeostatic communities and cultures. We find that, just as much as the surrender of common ground to successive waves of enclosures, the loss of the watermill as a centre of food production – owned and operated by and for the community – marks a fault line, a profound trauma in British history. Industrialisation replaced the grain mill with the mills of manufacture – cotton, paper, wool, steel, as elegised by Richard Jefferies and celebrated by J. M. W. Turner (Jefferies 1880; Rodner 1997). The mill is a recurrent mystical symbol in the writings of William Blake and even has a walk-on part in the early history of the information age: the analytical engine of Charles Babbage comprised the ‘store’ and the ‘mill’, precursors of the memory and central processor of modern computers (Swade 2002: 105).1

One of the most famous literary watermills instructed its cultured, largely urban readership in the dangers of neglecting – and, importantly, neglecting by misreading – the watermill as a site. Although Don Quixote (1606, 1615) is better known for its ‘tilting at windmills’ episode, Cervantes’ antique knight makes a similar mistake when he approaches two watermills. Sancho Panza, a former farmer, sees what is before him: ‘two large watermills in the middle of the river’, which he further explains as ‘watermills … where they grind wheat’. Don Quixote sees something quite different. ‘[A]lthough they seem to be watermills’, he explains, ‘they are not’: ‘There, my friend, you can see the city, castle, or fortress where some knight is being held captive, or some queen, princess, or noblewoman ill-treated, and I have been brought here to deliver them’ (Cervantes 2005: 650)

Their boat caught in the fast-flowing millrace, it is Quixote and Sancho who have to be rescued by two floury-faced and exasperated millers. As Harry Levin remarks, in the figure of Don Quixote Cervantes explores the relationship between ‘literary artifice and that real thing which is life itself’ (Levin 1959: 81). Elsewhere, we have considered the tendency among scholars and literary critics to read literary representations of watermills as something, anything, other than what they are, and for what they do: namely, places ‘where they grind wheat’ (Archer et al. 2015a). Like the Golden Age knight, on occasions literary critics and modern readers should perhaps be willing to attend to the words of Bishop Joseph Butler: ‘Everything is what it is, and not another thing’ (1726: 19). Watermills are ‘real things’, places where wheat is ground. Watermills happen to people, and as a result they are material presences in literature and culture. The cost of neglecting to consider the watermill in such terms is to fail to understand the important lessons millers’ tales can tell us about the role of food production in sustainability – lessons that are vital to our own and future wellbeing.

Tales of water, wheat and self-sustaining communities

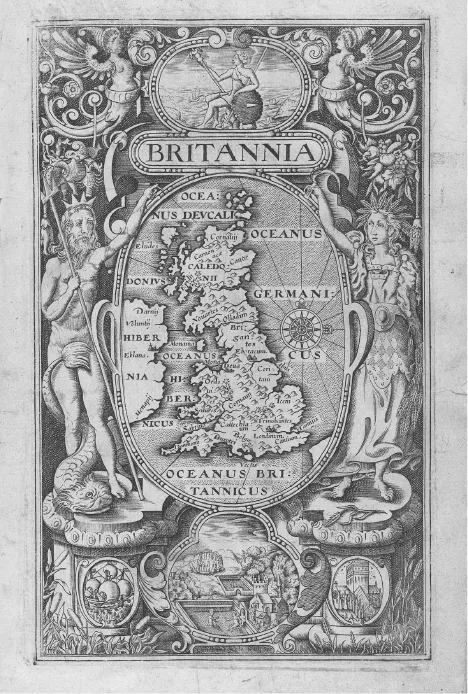

In poetry, prose and the visual arts, Britain has been celebrated as an island formed and powered by the interaction of water and wheat. In the frontispiece to William Camden's Britannia (1586, 1610: 3), a cartographic rendering of the British Isles, seemingly certain in its locations and relative dimensions, is accompanied by two classical deities (Figure 1.1). To the left is Neptune, god of the sea, and to the right is Ceres, the corn goddess. Just as much as the mapped part of this frontispiece, the presence of the gods of sea and corn reveal an important truth about the history of these islands. The matter of Britain is enlivened by the meeting and interaction of sea and land, water and wheat – what Thomas Hobbes, writing in 1651 called ‘the two breasts of our common Mother’ (1985: 285). When these resources are exploited in a sustainable fashion, Camden explains, Britain can not only feed herself, she can afford to export overseas, thereby fuelling her own imperial ambition.2

Writing over 200 years later, John Keats was also able to imagine a ‘Kingdom of Corn’, albeit one no longer associated with a particular place in the present, but one seemingly lodged in the mythical past: the golden age of a Virgilian autumn. Keats's Apollo addresses the three Graces:

Which of the fairest three

To-day will ride with me?

My steeds are all pawing at the threshold of the morn:

Which of the fairest three

To-day will ride with me

Across the gold Autumn's whole Kingdom of corn? (Keats 1988: 56)

Embedded within these seemingly abstract and timeless visual and literary references is an urgent and determinedly time-bound politics of food supply. Camden and Keats wrote not in times of abundance, but in times of dearth. The period 1580–1610 witnessed a run of poor harvests. In a series of initiatives, the state attempted to control the production, processing and distribution of grain; when those measures were perceived to fail, riots broke out in London and the Midlands.3

Keats wrote amidst febrile debates concerning responses to the spiralling corn prices generated by the 1815 Corn Law and cheap labour exacerbated by the influx of soldiers returning from the Napoleonic Wars (Barnes 1930: 117–84; Gash 1978). Proposals for a second Corn Bill were debated in Parliament during late 1818 and early 1819. The impact of these factors on the prices and distribution of food led to increasing food insecurity (and profoundly influenced Keats's poetry at that time; see Marggraf Turley et al. 2012). It was a situation likely to result in revolution, as Byron warned in The Age of Bronze:

For what were all these country patriots born?

To hunt, and vote, and raise the price of corn?

But corn, like every mortal thing, must fall,

Kings, conquerors, and markets most of all. (Byron 1823: 28)

Allusions to corn, wheat and harvests in the works of Camden, Keats and Byron are not simply reworkings of a literary trope as old as Hesiod and Virgil. For all three British authors, the corn they write about is pressingly real and is part of a wider web of environmental conditions, political imperatives and socio-economic concerns – unsustainable times, with uncanny similarities to our own. Indeed, the interplay of water and wheat is, in turn, part of a much bigger story concerned with the sustainability of food production and distribution. Globally, more than 80 per cent of the land used for growing crops depends entirely on precipitation to support plant production. The remaining cropland is irrigated and supplies almost 40 per cent of the world's food and fibre needs. Ours is a thirsty planet. It takes about 500 tons of water to make 1 ton of potatoes. A ton of wheat needs 900 tons, maize 1,400 tons, and rice comes in at a mighty 2,200 tons (Mekonnen and Hoekstra 2010). The international trade in food can therefore be understood an international trade in water.

In the sciences, a proxy is a measurement of one physical quantity that is use...