![]()

1

‘Raking over’ Local Hero again: national cinema, indigenous creativity and the international market

More so than any other film examined in this book, and perhaps more so than any film in the history of Scottish cinema, Local Hero is a film whose critical reputation is very familiar, so much so that for a time it was commonplace for writing on Scottish cinema to express the need to talk about something else besides the film. In his Contemporary Scottish Fictions, Petrie said films such as Local Hero no longer require critical attention because of ‘the sheer familiarity’ of such analysis, as well as ‘a desire to move beyond the apparent obsession with these regressive tropes that have blinded many to the more productive achievements and traditions within Scottish cultural expression’ (2004, p. 204). Similarly, Martin-Jones concluded a report on a conference dedicated to contemporary Scottish cinema by remarking that the event featured scholarship on a variety of forms of Scottish film-making and that the field as a whole had ‘begun to focus more exclusively on the vibrant present, rather than feeling the need to rake over Whisky Galore! and Local Hero yet again’ (2005b, p. 155).

Petrie and Martin-Jones are here responding to a long and polemical tradition of Scottish film criticism which saw Local Hero as a crucial text for illustrating the deleterious effects of the market on a potential Scottish cinema. Writings from the seminal Scotch Reels collection to Petrie’s study in the mid-2000s have presented the film as a moment in which Forsyth, despite his promise as an emerging indigenous talent, succumbed to the worst kinds of regressive discourses of Scottish cultural representation. For many of these critics, the fact that this project was Forsyth’s first intended for an international audience was not a coincidence and the film has become an example par excellence of the necessity of subsidy systems for film production in Scotland. If properly managed, such systems, it has been argued, would shield film-makers from the demands of the marketplace and therefore keep them from following Local Hero’s lead and resorting to cultural stereotyping.

Before the film was even released some were voicing concerns over the ways the project would represent Scotland. Writing in his ‘The Iniquity of the Fathers’ essay in Scotch Reels, McArthur articulates some of these fears:

In his article calling for a ‘Poor Celtic Cinema’, McArthur let it be known that his fears had been well founded. Arguing that the film bowed too much to the marketplace, he called it ‘ideologically equivalent’ to films like The Maggie (Alexander Mackendrick, 1954) and Brigadoon (Vincente Minelli, 1954) and goes on to describe the film as the ‘locus tragicus’ of a native Scottish artist coming ‘to live within the discursive categories fashioned by the oppressor’ (1994, p. 119). McArthur traces what he sees as Forsyth’s usage of culturally denigrating discourses to the specific industrial conditions surrounding Local Hero: ‘To offer an axiom to Celtic film-makers: the more your films are consciously aimed at an international market, the more their conditions of intelligibility will be bound up with regressive discourses about your own culture’ (1994, pp. 119 –120).

Writing in 2003, McArthur reiterates these views on Local Hero in his twin studies Whisky Galore! & The Maggie (2003a) and Brigadoon, Braveheart and the Scots (2003b). In these works, McArthur elaborates upon his views on what he sees as a group of films which show the tendency (which he terms the ‘Scottish Discursive Unconscious’) to represent Scotland and Scottish people in the regressive terms of tartanry and kailyardism. The four eponymous films and others, including Local Hero, represent Scotland, particularly Highland Scotland, as being outside of ‘the “real” world of politics and economics’ (2003a, p. 77). Petrie takes a similar view on Local Hero to that expressed by McArthur. While recognizing more complexity in the film than is generally granted, Petrie argues that the film’s ‘externally constructed romantic vision of Scotland […] serves to overpower the additional theme of existential loneliness and isolation associated with the character of MacIntyre’ as well as overshadowing several significant departures from the narrative conventions of what have become known as kailyardic films (2000a, pp. 155 –156).

Petrie adds ideological and historical dimensions to this reading of the film in Contemporary Scottish Fictions. Here he characterizes the film as a backwards step in an otherwise exciting, progressive epoch in the history of Scottish cultural production. Contextualizing the film within Forsyth’s early output, which Petrie considers to be part of the ‘Scottish cultural revival’ of the early 1980s, he calls Local Hero ‘a temporary retreat into a more stereotypical representation [of Scotland] for mass consumption’ (2004, p. 61). The film is excluded from Petrie’s section on Forsyth’s early work, which is presented alongside the novels of James Kelman and Alasdair Gray as well as the television work of John Byrne, because Petrie is concerned with works which he feels show ‘a creative engagement with contemporary experience’ of Scotland in the 1980s (2004, p. 61). In other words, Local Hero is implicitly characterized as a film that exists outside the domain of ‘important’ history because it offers no reflection on the life of Scots during this period. It is thus not surprising that in concluding his study, Petrie counts the film amongst the ‘market-driven distortions’ which he excluded from his history of the period (2004, p. 209).

More recently, critics and historians have contested these claims, pointing out the extent to which Forsyth knowingly parodied and pastiched the conventions of kailyardism in the film (e.g. Meir 2004, 2008; Sillars 2009). Ian Goode has shown that the film offers a multifaceted treatment of Scottish landscapes that goes beyond the scope of tartanry and aspires to a progressive environmentalist discourse (2008). Martin-Jones has discussed Local Hero specifically and Forsyth’s comedy generally as important components of Scottish popular cinema in the 1980s (2009, pp. 24 –30). Jonathan Murray (2011, pp. 71–100) synthesizes many of these insights into an auteurist account of the film that shows the ways in which Forsyth’s unique brand of humour as well as his approach to mise-en-scène allows the film-maker to make powerful statements about national identity, globalization, environmentalism and life in an age of neo-liberal capitalism.

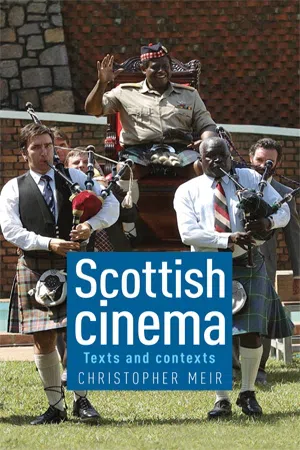

This chapter seeks to build on the fruits of this collective rethinking of Local Hero while also hoping to more thoroughly flesh out the ways in which the film is, contra McArthur and Petrie, in many ways a document of its time, reflecting on its political context and engaging with the lived experiences of Scottish people. As we see, this involves more than the film’s pastiche of Scottish representational discourses, which is, nevertheless, crucial to appreciate as are the many jokes that Forsyth makes at the expense of national identity generally. The chapter also more thoroughly examines the relationship between Forsyth and the international market, an exploration that focuses on the genesis of the film from the partnership between Forsyth and David Puttnam (Figure 1) as well as issues related to the marketing and distribution of the film. Importantly, all of these issues are shown to be interrelated and by the end of this chapter we see in the making of Local Hero a balancing act between the artist and the market that acts as a template for many of the case studies that follow in this book.

Figure 1 Bill Forsyth (left) and David Puttnam (right) on location for the filming of Local Hero

The film itself: comedy, nation and politics

In his study of Forsyth, Murray argues that in part because of the uniquely gentle tone of his comedy and his deferential and self-deprecating media persona, many have come to underestimate the seriousness of the director’s work (2011, p. 3). In his view, this helps to explain the negative reception of Local Hero as it was easier to assume that an indigenous film-maker had succumbed to the pressures of the international market than to assume such a genial comedy – made by such a seemingly genial man – had any deeper critical agenda (p. 74). When it comes to many themes, including Scottish representation, this misapprehension has been thoroughly debunked. The kailyard ideal of Ferness is knowingly shown in Local Hero to be a myth manufactured by the villagers to sell the town to the rich tourist Mac (Peter Riegert), who has come on behalf of an American oil company to literally do just that: buy the town. The iconography of the tartan and kailyardic traditions of Scottish representation, from the magical Highland mists to the ceilidh and the outsider ‘going native’ and marrying a local girl, are systematically invoked by Forsyth only to be undermined or lampooned in the film. The film thus cannot be seen as a simple reiteration of what one critic called the ‘Whisky Galore! syndrome’ (Brown, 1983, p. 158) but is instead more of a pastiche of that tradition, pastiche being a practice that acknowledges the historicity of its representational traditions whilst also enjoying the same pleasures of the original (Dyer, 2007).

Understanding Forsyth’s pastiche of tartanry and kailyardism is extremely important to fully appreciating the film and its director, but the depth of Forsyth’s satirical project goes beyond these discourses. As described above, McArthur has criticized the film’s depiction of the village as existing outside ‘the “real” world of politics and economics’ (2003a, p. 77). Alistair Michie likewise places the film within the context of representations that present ‘the isolated community, shut off from “reality”, detached from history’ (1986, p. 258). By excluding the film from his study of Scottish fictions which reflect upon the Scottish condition during the Thatcher years, Petrie implicitly echoes these sentiments. Such assessments, however, overlook the film’s pointed satire of the economic and political realities confronting Scotland and Britain in the1980s. Local Hero is actually very much a film of its time, and the village of Ferness is anything but an isolated community set apart from the world of politics, economics and history.

Reaganite/Thatcherite corporate capitalism is the narrative’s catalyst and Mac is in many ways the epitome of the ‘yuppie’, the social class that became synonymous with the decade. British economic and political complicity with America during this period is likewise apparent in the film. Early in the film Happer’s (Burt Lancaster) secretary (Karen Douglas) is overheard connecting a call from a female prime minister, a thinly veiled reference to Margaret Thatcher. Forsyth takes this opportunity to poke fun at Thatcher’s ‘Iron Lady’ persona when the secretary chats with the Prime Minister regarding a dessert recipe they shared (‘Yes ma’am, I tried it with the raspberries, it was delicious’). However brief this joke is, it nonetheless lampoons the close relationship between the British government of the time and American big business, the basic joke here being that one of the world’s supposedly most powerful political leaders must wait on hold to talk to the CEO of a major American corporation. In that respect the film’s Thatcher is no more significant to American businessmen than the unnamed third world leader (‘his serene highness’ as the secretary calls him), who must also wait his turn to speak to the actual world power in the film, that being American big business.

The presence of the British government in the film does not end here. The occasional flyovers by fighter jets punctuating the film’s action remind the audience that the Highlands are not untouched by the militarism that marked the Cold War era generally and Thatcher’s government in particular. Forsyth’s script is frank about the import of this motif. While Victor and Mac wander around the town the morning after the ceilidh they idly watch the planes overhead. Forsyth’s directions in the script characterize the link between those planes and the story’s Cold War context: ‘Beyond [Victor and Mac] the rehearsals for the Third World War are underway’ (1981, p. 116). The fact that these jets sometimes test their weapons so near to Ferness that the clouds from the explosions are visible shows that the British government is also exploiting the remote Highland landscape for its own purposes, though without offering to compensate the locals. Keeping with the film’s overall ironic tenor, Mac at one point comments on these training exercises by saying that they ‘spoil a pretty nice country’.

The occasional appearance of the ‘real’ world’s tools of mass destruction speak not only to Thatcherite militarism but also to the Cold War which provided the occasion for much of that militarism. Forsyth also draws on this aspect of the film’s historical context. One of the film’s most memorable characters is Victor (Christopher Rozycki), a sailor from the Soviet Union who comes to town to attend the local ceilidh and to check up on his investments, which are being managed by Gordon. Together with the town’s African minister Reverend Macpherson (Gyearbuor Asante), Victor reminds us that Ferness is not an isolated town cut off from the outside world, but is instead ‘globalized’ in its own way (Murray, 2011, p. 85). Victor’s presence in the film also allows for a number of jokes on Cold War...