![]()

1

Introduction

South Africa and the United States of America, two countries with notorious histories of racial violence, attempted to formally deal with their violent pasts at roughly the same time. Eight years after Apartheid had formally ended and seven years after the Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation Act of 1995 brought the body to life, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) delivered its final report in 2002. The extensive report laid bare the sordid details of the violence that had been committed in the name of Apartheid and called on the new democratic government to make restitutions for the pain and hardship inflicted on thousands of Apartheid’s black victims. Two years later, on 17 June 2005, the US Senate approved Resolution 39, formally apologizing for the body’s failure to enact a federal anti-lynching law in the course of the twentieth century. According to the two senators who sponsored the resolution, the idea of a formal apology arose after they had read Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography in America, a graphic and disturbing pictorial history by James Allen.1

The TRC and Senate Resolution 39 were part of efforts to “bring closure” to the painful racial past, but they did so in very different ways. The TRC was a formal state body, established and fully funded by the post-Apartheid state. Its report also marked the culmination of a massive investigation modeled on the lines of a criminal court inquiry that succeeded in sending to jail a number of violent perpetrators. Its work embroiled millions of South Africans in its remarkably transparent and comprehensive procedures. In contrast, the passage of Resolution 39 was a perfunctory affair, the brainchild of two individuals, Mary Landrieu (Democrat, Louisiana) and George Allen (Republican, Virginia), who took it upon themselves to pilot a resolution through the workings of the Senate. Only a handful of senators were present when Resolution 39 was read; if a roll call had been taken, it would have recorded that two senators from Mississippi, the state that yielded the most lynchings in the South, were not even present when the vote was taken. “The moment lacked the drama of the fiery Senate filibusters that blocked the legislation three times in the past century.”2 The irrelevance of Resolution 39 seems to confirm Elliot Gorn’s lament that “Increasingly, Americans are a people without history … which means … a people reluctant to engage difficult ethical issues.”3

The TRC and Resolution 39 were two very different ways of dealing with the painful past. If the TRC signaled the full involvement of the state in dealing with the violent past, Resolution 39 was a telling reminder of the indifference with which the US government dealt with the summary killing of African Americans in the first half of the twentieth century. The TRC and Resolution 39 therefore provide a useful starting point for a comparative study of racial violence in South Africa and the United States because they highlight the different roles that the state played in that violence.

The extensive work of the TRC in post-Apartheid South Africa serves as a metaphor for the systemic and vanguard role that the state played in forging and maintaining the racial order over the course of the twentieth century. From the outset of its emergence in 1910, South Africa’s unitary state set out to promote the interests of its white citizens. Drawing on a racially discriminatory constitution, state managers after 1910 elaborated an official policy of “segregation” that authorized them to manage the field of “race relations.” Interposing itself between black and white subjects, the state claimed the monopoly over the means of racial violence and undertook explicitly discriminatory legislation that an expanding array of oppressive institutions would enforce over the next eight decades. As in all such monopolies, state control was never so effective or total to preclude unofficial white violence against blacks.

Unofficial violence was particularly high in the white rural areas and the gold mining industry, where individual whites were notorious for launching brutal and lethal attacks on unarmed blacks. However, it was only under exceptional circumstances that white citizens staged collective attacks against blacks. Collective violence against blacks was not unknown, but it occurred infrequently and usually in moments of extreme intra-white violence, such as in the course of the Anglo-Boer War, the armed Rebellion of 1914 and the violent strike of 1922, prompting historians to recently abandon the idea that these events amounted to “white men’s conflicts” in which blacks played little or no role.4 Still, however much they were involved in internecine white violence, blacks were neither the primary protagonists nor the targets of the various conflicts that tested the foundations of the emerging state. Moreover, violent upheavals amongst whites alarmed state managers who feared that blacks might capitalize on white disunity and encourage them to challenge white supremacy. The subsidence of these intra-white wars, rebellions and strikes in the interWar years (1918–39) therefore prompted the state to intervene ever more extensively and deeply into society by assuming greater controls over all facets of blacks’ lives. The result was the consolidation of a tradition of elaborate and extensive state intervention in the twentieth century.5 The TRC remained true to this tradition of forthright state intervention into South African society. True to form, this state-supported enterprise managed to attach names and faces to the quotidian destruction of black life in a way that made it difficult for whites to deny their responsibility for racial violence.6

Resolution 39, in contrast, illustrates the halting and ambiguous, but always complicit, role that the state played in racial violence in the American South. Although it addressed one of the most repugnant episodes in American history, the resolution failed utterly to capture the national imagination. Mentioned only briefly in the national media, it failed to ignite a popular discussion about, let alone a national apology for, the horrors of lynching in twentieth-century America. Furthermore, it addressed only the Senate’s “failure to act,” omitting the role that the other branches of government played in the segregationist era. Most importantly, the resolution could not do what the TRC had so visibly done in its quest for racial reconciliation: it could not name names and hold specific individuals accountable for the extra-legal killing of the 4,742 lynch victims that the resolution alludes to. For almost all Americans who read reports of the resolution in their local newspapers, the victims remained as nameless and the perpetrators as furtive as they had been in the first half of the twentieth century. Who precisely was responsible for the “festival of violence” against blacks in the South?

In the same breath that it faulted the Senate for not passing anti-lynching legislation and for disregarding “repeated requests” by civil rights groups and several Presidents, the resolution also noted that the House of Representatives had managed to approve three “strong anti-lynching measures” between 1920 and 1940. In this way, the resolution alludes to the theory of divided government, suggesting that the fractured nature of the federal state complicated the task of racial justice. The light that Resolution 39 shone on lynching was shallow and confusing, mirroring the episodic attention that the state as a whole had earlier devoted to the summary killing of African Americans in the segregationist South. Perhaps the most telling aspect of the resolution, moreover, was its preoccupation with the Senate’s “failure to enact anti-lynching legislation.” This somewhat guarded language reinforced the image of a passive and Byzantine American state, hamstrung not by a systemic racism that implicated the state in racial lynching but by a fig leaf – the formal complexities of the federal system.

The ubiquity of racial violence in both South Africa and the American South has not escaped the attention of comparativist scholars, of course. But the literature shares a common deficiency. Virtually all of it focuses on formal structures and state policies. Accordingly, the literature is largely silent about the role that different forms of extra-legal violence played in the genesis and perpetuation of the two racial orders. To date, no major comparative work has considered interpersonal violence as a distinctive component of the broad field of “racial repression.” The comparative literature therefore imparts a good idea about the role that state bodies played in establishing segregation but virtually nothing about the extra-legal, unofficial violence that also shaped the two racial orders. This silence is surprising because unofficial violence was extensive in both contexts. Distinguishing unofficial violence from “repression” therefore directs attention away from the activities of formal bodies and highlights the violence that ordinary white citizens inflicted on blacks. By focusing on unofficial violence in the early stages of segregation in both countries,7 this study hopes to stimulate questions about a neglected phenomenon that tells us much about the development of distinctive forms and “styles” of white supremacy.

Private and communal violence

Unofficial violence assumes a variety of forms. Donald Horowitz, for example, distinguishes eight possible distinct incarnations consisting of violent protests, pogroms, feuds, lynchings, genocides, terrorist attacks, gang assaults and ethnic fights and notes, moreover, that various permutations of these give rise to “hybrid forms” of extra-legal violence.8 This study, however, is almost exclusively concerned with interpersonal forms of extra-legal violence. More precisely, it is concerned with lynching.

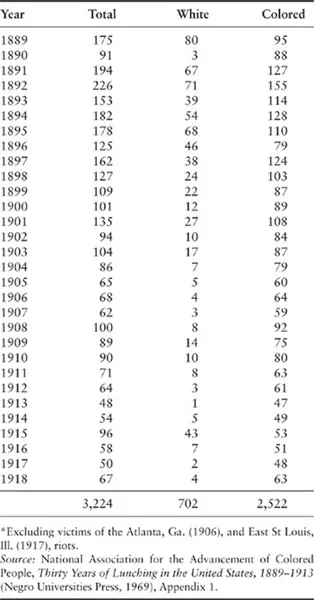

Lynching was the iconic form of racial violence in the American South and the most emotionally fraught development in racial segregation after the Civil War (see table opposite). Lynching pervades the history of the New South and has generated a vast and still expanding scholarship devoted to the institution.9 In contrast, lynching was virtually absent in South Africa. The word was occasionally used in South Africa after 1910, usually by whites to warn what might happen in the absence of stern laws and sterner policemen. In South Africa, one source notes, “the banding together of groups of whites in small towns and villages to engage in frenzied attacks, involving violent and obscene rituals, upon defenseless Africans … was almost non-existent.”10

Why was extra-legal racial violence fundamental to segregation in the American South but of minor importance in South Africa? In response to this broad question, the book distinguishes between two cultures of violence: a bureaucratic tradition of racial violence in South Africa and a lynch culture in the American South. It argues that a tradition of bureaucratic paternalism in South Africa suppressed communal forms of extra-legal violence and tolerated only private violence against blacks. In South Africa, virtually all lethal unofficial violence took the form of common murder. In contrast, a full-blown lynch culture tolerated all forms of racial violence. Racial violence in the South was limited only by the imagination of white killers and incorporated everything from murder to communal (or “spectacle”) lynchings. Focusing on the first half of the twentieth century, the book explores the contrast between these two cultures of violence through the prism of three institutions that were central to both cultures of violence: the racially repressive labor market, theological justifications of white supremacy, and the legal system.

Explaining why interpersonal racial violence in South Africa was limited to private violence whereas communal racial violence was widespread across the American South is therefore the principal focus of the book. Like other comparative studies of the two countries, this study also draws attention to the many similarities between the American South and South Africa with regard to white supremacy. However, the organizing question of the study emphasizes their differences: why was communal violence so fundamental to the making of segregation in the American South but almost entirely unknown in South Africa? In the process of illuminating this issue, the study casts light on a broader complex of social, political, and cultural practices that led to the development of distinctive “styles” of white supremacy. Focusing on unofficial violence is therefore useful, not only because it sheds light on a neglected phenomenon in the comparative literature but also because it demonstrates that distinct patterns of extra-legal violence require the involvement and support of a broad array of institutions and dispositions in society.

White and colored persons lynched in the United

States, 1889–1918*

A distinction that William Fitzhugh Brundage underscores in his acclaimed book, Lynching in the New South: Georgia and Virginia 1890–1930, provides a key to understanding the difference between the American South and South Africa. Based on the analysis of more than 600 lynchings, Brundage’s book devotes sustained attention to the difference between “private” and “communal” lynchings. This analytical distinction clarifies the unique element and the central puzzle of this comparative study.11

At the most obvious level, the distinction between private and communal lynching is one of form and scale. Private lynchings were extra-legal murders that whites often carried out furtively. The victims of private lynchings would usually be discovered hanging from trees or bridges or shot to death on lonely roads; or they might be killed in the presence of a few witnesses. In all of these instances, individual white citizens usually acted alone and resorted to summary physical violence to discipline or kill specific blacks who offended them. Still, even a hanged corpse was not prima facie proof that a lynching and not just a “murder” had taken place. In 1909, when the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) launched its campaign to secure a federal law that specifically criminalized lynching, the legal route that the organization chose compelled it to offer a definition that would clearly distinguish “lynching” from “murder.”12 In South Africa, a specific legal response to lynching was unnecessary because lynchings did not occur. White South Africans certainly murdered blacks in large numbers as the twentieth century proceeded. But the furtive nature of these extra-legal killings meant that it was not always easy to clearly distinguish private lynching from common murder. The use of ropes to hang victims and other forms of killing was rare in South Africa, where the great majority of racial murders were secured with guns or fists. South Africa’s criminal code accordingly disaggregated all murder into various classes, such as culpable homicide, manslaughter, and murder in the first, second and third degrees.13

In contrast to private lynchings, communal lynchings were dramatically different affairs that dispensed with the problem of definitional precision. Communal lynchings in the South occurred in the public sphere, were attended by groups that could be as small as 25 or as large as 25,000, and were frequently announced ahead of time in newspapers, from the pulpit, and by word of mouth. Local luminaries and law enforcement officials brazenly comported themselves at the head of the crowd, while prominent officials, including state governors and US senators, openly championed the cause of violent mobs. In many cases, photographs were made of the event, converted into postcards and sold in local stores. Communal lynchings accounted for approximately one-third of all known lynchings between 1890 and 1930. However, the image of large crowds standing before a dangling black body cast a long shadow and strongly influenced the analysis of lynching in the New South.14

In South Africa, however, communal lynching was entirely unknown. It also seems to have been unthinkable. The collective killing of blacks did occur in South Africa, but it assumed the form of “massacres” perpetrated by law enforcement agencies. Police and army units acting under standing orders regularly mowed down unarmed Africans who protested against various aspects of government policy or opposed the administrative regulations that mushroomed from 1920 onwards. Typified by the infamous Bulhoek massacre in 1921 and underscored by numerous lesser and unsung massacres in the urban and rural areas, a tradition of bureaucratic violence became the signature of segregation in South Africa.15 Still, state officials who frequently used “excessive violence” against unarmed and anonymous Africans differed sharply from the men who summoned festive white citizens to commit extra-legal violence against specific victims in the New South.

Beyond the issue of form and scale, however, private and communal lynchings are also distinguished by another important difference – the extensive use of symbolic or ritual violence in communal lynching. Private lynchings and more prosaic forms of racial murder in the South were generally summary affairs in which rituals were either entirely absent or only of minor importance. Men who committed private lynchings may have desecrated the victim’s body, but the rapidity or furtiveness of the killing limited the symbolic impact of such gratuitous violence. The same cannot be said of communal lynching, which was dominated from beginning to end by symbolic functions that loomed larger and reverberated longer than the actual death of the victim. More often than not, the lynch victim would be disfigured before, during and after his death, and the remains of the body were often carved up and sold as mementos. Together with its highly public nature, the extensive use of ritual torture in communal lynching commands attention. Whereas private lynchings symbolized the prowess that individual white men enjoyed over all African Americans, com...