- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Offers new insights into the early modern sickness experience, through a study of the medical history of Wales

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Physick and the family by Alun Withey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Disease and mortality in early modern Wales

1

Disease and Welsh society

‘The gentry in general are pretty hearty in the Countrey [sic]. It’s the common sort that drop off’.1

So wrote the Anglesey curate Owen Davies in March 1729 as an epidemic fever swept through his area. In many respects, however, his wry comment does represent something of the true situation in early modern Wales, since social status could have a strong influence on both susceptibility to disease and the chances of survival.

By the early eighteenth century, the population of Wales is estimated to have been around 400,000 following a pattern of growth which had begun in the Middle Ages and which continued through centuries afterward.2 Large parts of Wales were given over to an agrarian economy and the majority of people lived in predominantly rural areas.3 The lowest strata of Welsh society, the poor, was also the biggest, estimated by Glanmor Williams as being up to three-quarters of the population, while the biggest single occupation of the ‘average’ Welsh person as late as the nineteenth century was that of farm labourer.4 The houses of the majority of the lowest orders of society were often dark, damp and uncomfortable, and offered scant shelter against the elements.5 While writers extolled the healthy Cambrian landscape, they did not feel similarly well disposed towards Welsh houses. English visitors often spoke disparagingly of conditions in such houses and descriptions of ‘hovels’ and ‘miserable huts’ are characteristic. One notorious book about Wales and its people described a Welsh dwelling as ‘a Dunghill modelled in the shape of a cottage, whose outward surface was so all to-be-negro’d with such swarthy plaister that it appear’d not unlike a great blot of Cow-Turd’.6 Whilst clearly designed to be provocative, there is undoubtedly an element of truth behind the barbs. As late as the nineteenth century, an English writer, Walter Davies, wrote of labourers’ cottages in North Wales that ‘One smoky hearth, for it should not be styled a kitchen, and one damp litter cell, for it cannot be called a bedroom, are frequently all the space allotted’ to six or seven people, adding that ‘three fourths of the victims of the putrid fever perish in the mephitic air of these dwellings’.7 Amongst the less fortunate, death rates rose in this period as the effects of a combination of epidemic diseases, poor harvests and rising grain prices tended to weed out the weak and vulnerable.8 Conversely, wealthy gentry families living in better housing, and with presumably better living conditions, actually saw average life expectancy at age five improve by around five years for every quarter century between 1550 and 1750.9

Welsh travellers within the country were also aware of the sufferings of their fellow countrymen. Whilst accompanying the Duke of Beaufort on his 1684 tour of the Principality, Thomas Dineley wrote of one area in Cardiganshire that ‘The vulgar here are most miserable and low as the rich are happy and high both to an extream’.10 The tradition of will making, even amongst the less well off, also affords a glimpse into the types of conditions that the less fortunate endured. One 1630 will provides a rare mention of housing, listing ‘a house or cottage’ valued at one pound, together with only two other belongings, a bed-sead and hutch, comprising the meagre acquisitions of a poor man.11 Another frequent remark is the lack of space in such dwellings, where often large families shared a single room.12 Such cramped and crowded living quarters afforded much opportunity for infections to spread within households and were compounded by the common practice of sharing living space with animals. Straw covered clay floors could become infested with fleas from animals, and stinking from urinal and faecal contamination.13 Unwashed bodies, often infested with lice, provided further opportunity for the spread of disease from person to person, and lice were active at all seasons of the year, causing a range of symptoms from skin infections to fevers.14 Moreover, the proximity of animals and poor construction of houses also provided a fertile breeding ground for flies, especially houseflies, blow flies and flesh flies, all capable of spreading deadly diseases such as bacillary and amoebic dysentery, typhoid and tuberculosis, all of which were widespread in Wales.15 Lack of adequate heating made cold winters especially difficult and it was often the poorest and weakest who succumbed during prolonged periods of poor weather. We should note that this situation was not universally applicable however.

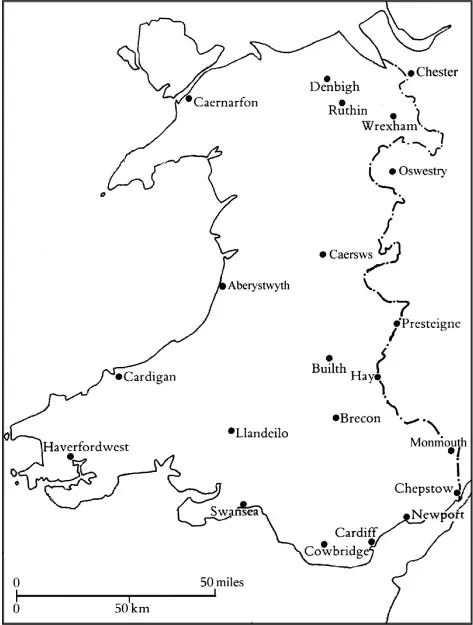

We should also not ignore towns and urban Welsh patterns of disease. Wales in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries boasted no cities, relying instead on external ‘regional capitals’ of Bristol in the South, Chester in the North and Shrewsbury along the Welsh Marches.16 There were few towns with more than 2,000 inhabitants– one notable exception being Wrexham– yet appreciation of the importance of such towns to Welsh economic, social and cultural history has grown markedly in recent years.17 In the early modern period, contemporaries saw towns as unhealthy, noisome and pestiferous places where disease and poor health were almost unavoidable companions to the urban dweller. Townsfolk were often derided as idle and prone to worry, which sapped their health and gave them poor digestion leading to more serious complaints.18 The presence of large groups of people in close proximity proved a fertile breeding ground for all manner of epidemic and endemic diseases throughout the early modern period.

1 Map of Wales showing major towns

Water supplies were often contaminated as people empted their waste into the nearest available stream or river. Rich and poor lived cheek by jowl, sanitation was rudimentary and raw sewage and animal detritus frequently fouled the streets in which children played. In 1594, charges were brought against two bailiffs for ‘suffrynge dy[ver]s abuses’ in Cardiff, relating to the disposal of dunghills, and also for ‘nott cawsynge ye highewayes’.19 Clearly this problem bedevilled early modern towns since, even as late as 1740, the authorities of Aberystwyth were forced into legislation to prevent inhabitants from ‘lay[ing] downe their dunghill opposite their doors’.20 Anything from the unwashed bodies wearing filthy clothing, harbouring a multitude of vermin, to the immorality and drunkenness of the townspeople, to the foul and noxious odours of the urban environment could bring disease and spell disaster for the early modern town.21

Plague was certainly present during the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries in Welsh towns, although it appears to have made less impact here than in some parts of England. Chester was one area that suffered greatly, with 650 people dying of the plague there in 1603 and 986 in 1604.22 South and mid-Wales were hit badly in the late 1630s, with outbreaks in Llanidloes, Machynlleth and Newtown while north Wales, especially Wrexham, was hit in 1631. The years 1637–38 were apparently bad for plague across all parts of Wales and the diarist Walter Powell reported in 1639 that the disease was also ‘very hot in diverse parts of Monmouthshire’.23 One of the most prolonged outbreaks in Wales occurred in Presteigne in Powys, lasting from August 1636 until June the following year. Here, the authorities were forced into desperate measures to try and contain the epidemic by restricting public movements and even threatening to halt food supplies if people attempted to leave the town.24 This outbreak seems to have provoked much popular fear in surrounding areas, and one man from the neighbouring parish of Upton on Severn was apparently even bound over for threatening to go to Presteigne in 1637 in order to deliberately bring the plague back upon his wife and children.25 In general, plague visitations were more virulent in towns although not exclusively, as the outbreak in rural Bedwellty parish which killed 82 people in 1638 demonstrates.26 The last reliable reports of an outbreak in Wales occurred in 1652 in Haverfordwest and Carmarthen, the disease wreaking havoc amongst populations and reportedly stretching resources in Haverfordwest almost to breaking point.27 Wales, however, does appear to have escaped relatively unscathed in terms of the impact of bubonic plague, at least in comparison ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- List of figures

- Introduction

- Part I: Disease and mortality in early modern Wales

- Part II: Medical knowledge in early modern Wales

- Part III: Domestic sickness and care in the Welsh home

- Appendix A Selection of Welsh disease terms with English translations

- Appendix B Poor relief in Llanfyllin, showing payments made to parishioners in 1673 and 1674, and stated reasons for relief

- Select bibliography

- Index