- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

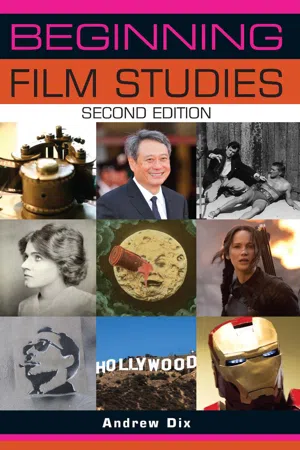

About this book

The perfect one-stop-shop for anyone starting film studies.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Seeing film: mise-en-scène

In starting to think about film’s distinctiveness as a medium, it might seem perverse to take instruction from study of another art form. However, the American New Critics, influential in mid-twentieth-century literary scholarship, are valuable to us in identifying a sin they call ‘heresy of paraphrase’. New Critics have in mind here readings of a piece of poetry or prose which attempt prematurely to say what it means and show, by contrast, little interest in or even knowledge of precisely how it means. Thus the paraphrasing heretic asserts what a Shakespeare sonnet is expressing about true love, but fails to consider how the poem’s thematic implications only emerge through its complex work of versification, rhyme, metaphor and syntax. The result is a disembodied kind of literary criticism, curiously inattentive to the specificities and textures of its own object of study.

Much of the discussion of film with which we are most familiar is weakened by similar insensitivity towards the particularities of the medium itself. The reader of newspaper film reviews and the viewer of TV programmes on cinema tend to encounter, precisely, heresies of paraphrase. Such discourse typically summarises a film’s narrative turns, or discusses its characters, but leaves unaddressed its material distinctiveness: its modes of cinematography, say, or its key editing choices, or its layerings of sound. Yet to be concerned with such issues of cinematic form is not indulgent, or somehow minor in relation to more essential things we should be doing as students of film. On the contrary, any attempt to ask larger cultural or ideological questions about a film is inadequate if it does not include some reckoning with the work’s formal dimensions. These visual and auditory repertoires should not be set aside, but, instead, actively explored as devices for the generation of meaning. ‘The meaning of art’, according to two Russian critics early in the twentieth century who were as absorbed by cinema as they were by literature, ‘is completely inseparable from all the details of its material body’ (Bakhtin and Medvedev, 1978: 12).

Film’s ‘material body’ is thus the subject of this book’s first three chapters. Before turning in Chapters 2 and 3 to editing and soundtrack, we begin with an account of film’s visual properties, grouped together under the French term mise-en-scène.

Defining mise-en-scène

‘What is mise-en-scène?’ asks Jacques Rivette, a key member of the New Wave, that group of filmmaker-critics which energised French cinema in the late 1950s and 1960s. ‘My apologies for asking such a hazardous question with neither preparation nor preamble, particularly when I have no intention of answering it. Only, should this question not always inform our deliberations?’ (Hillier, 1985: 134). While Rivette’s disinclination to define mise-en-scène is alarming, he valuably insists here upon the fundamental importance for film studies of engagement with particularities of visual style. What, exactly, is it that we see and give significance to as we watch films?

Consider the start of Sam Mendes’s American Beauty (1999), as a fade-in takes the viewer from a black screen disclosing nothing to a scene abundant in visual information. As the sequence begins, we see a young woman lying on a bed. While this figure remains silent and inert, the spectator begins interpretative work, making provisional assessments of the significance of her location, appearance and posture. Lit harshly rather than flatteringly, the woman is without both make-up and stylish clothing, hinting at some disregard for normative Western femininity. For the moment, we may be concerned just to register and process this sort of visual detail, utilising the categories of setting, props, costume and lighting. To these critical subdivisions should be added that of acting or performance, even while the woman lies motionless. However, our eyes may be more mobile and inquisitive still, taking in not merely the figure on the bed but also the distinctive ways in which shots of her are composed. What are the implications of the camera’s close proximity to her, admitting no other human presence into the visual field? And what seems connoted by the roughened texture of the image itself, shot on grainy video rather than 35mm film?

In carrying out interpretative work of this kind on a film’s visual specificities, the spectator is considering mise-en-scène. As Rivette says, however, the term is ‘hazardous’, open to several competing definitions. It translates from French as ‘staging’ or ‘putting into the scene’, indicating its origins in theatre rather than cinema. The theatrical bias of the word is apparent even in the most recent edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, which offers a primary definition of ‘staging of a play; the scenery and properties of a stage production; the stage setting’, but gives no acknowledgement of the appropriation of mise-en-scène as a term in cinematic analysis. The shadow cast by the theatre extends into film studies itself, where some scholars – notably, David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson in their influential Film Art: An Introduction – choose to define filmic mise-en-scène exclusively by what it has in common with theatrical staging: setting, props, costume, lighting and acting. Were we to arrest our analysis of American Beauty after considering such visual properties as the abrasive lighting or the woman’s stillness, we would be doing mise-en-scène work of this circumscribed, theatrically derived kind. But if the spectator goes on to acknowledge and evaluate other information offered to the eye – the camera’s framing of the woman, say, or the video footage’s imperfect quality – then he or she is pursuing instead that more expansive and satisfactory approach to mise-en-scène which embraces not merely the elements cinema shares with theatre but also visual regimes that are distinctive to film as a medium: all those things summarised by John Gibbs as ‘framing, camera movement, the particular lens employed and other photographic decisions’ (2002: 5).

This chapter adopts the broader of these two understandings of mise-en-scène. After first discussing the elements that film carries across from theatrical staging, it goes on to consider aspects of cinematography. Even such an expansive definition of filmic mise-en-scène is open to dispute as narrow and arbitrary. Jean-Luc Godard, another major figure in the French New Wave, writes with regard to a particular editing practice that ‘montage is above all an integral part of mise-en-scène’ (Narboni and Milne, 1972: 39). Bernard F. Dick, in a much-used textbook in film studies, suggests somewhat eccentrically that sound, too, should be accounted an element of mise-en-scène (2002: 19). While sound’s contribution to the sum of a film’s meanings is fundamental – in the scene from American Beauty, a man’s voice from off-camera modifies the sense of isolation that is visually implied – the proposition which Dick makes is one, for the moment, to resist in the interests of isolating the peculiarly visual components of cinema. Similarly, while Godard shows a proper distaste for any approach to film that underplays the effect of combining shots, the approach to mise-en-scène that is elaborated in this chapter still finds it valuable to identify visual elements that may be uncovered even in a single shot and thus to reserve until later the discussion of editing.

Pro-filmic elements of mise-en-scène

Coined in the 1950s by the French philosopher of aesthetics Etienne Souriau, the term pro-filmic refers to those components of a film’s visual field that are considered to exist prior to and independent of the camera’s activity: namely, the elements of setting, props, costume, lighting and acting (or performance) which cinema shares with forms of staged spectacle such as theatre, opera and dance. The artificiality of separating these things from cinematography is immediately apparent: Jennifer Lawrence’s looks of concern for her endangered sister in The Hunger Games (2012) – instances of performance, therefore pro-filmic – would not signify so vividly were it not for the film’s close-ups and close shots of her (examples of cinematography). Nevertheless, with the proviso that ultimately they will be reintegrated with cinematography itself, we begin here by separately considering film’s pro-filmic strands.

Setting

Cinematic settings vary in scale from the vertiginous interplanetary spaces confronting Sandra Bullock at the outset of Gravity (2013; see Figure 2) to the coffin that, patchily illuminated by a cigarette lighter and the glow of his phone, confines the protagonist in Rodrigo Cortés’s Buried (2010). In opulence they stretch from the Roman palaces of epics or the sumptuous interiors of Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014) to the hellish lavatory that Renton occupies in Trainspotting (1996). While some film settings advertise their artificiality, others, by contrast, evoke what Roland Barthes calls ‘the reality effect’: at one end of the spectrum, the fantastical Yellow Brick Road in The Wizard of Oz (1939); at the other, teeming city streets that have been exploited throughout cinema history (from brief ‘actuality’ films made in France by the Lumière brothers during the 1890s, through Italian neo-realism of the 1940s and early 1950s, to instances of modern Latin American cinema such as Amores perros (2000) and City of God (2002)).

2 Interplanetary space as setting: Sandra Bullock in Gravity (2013)

Whether expansive or narrow, magnificent or squalid, artificial or naturalistic, film settings compel our attention. They are not merely inert containers of or backdrops to action, but are themselves charged with significance. At the most basic level, locations serve in narrative cinema to reinforce the plausibility of particular kinds of story. An American urban crime drama would be sterile and unconvincing without the run-down street, the neighbourhood diner, the dimly lit bar; similarly, to guarantee the integrity of its fantastical story-world, Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy (2001–3) requires enchanted forests, shimmering lakes and towering precipices. As these brief examples suggest, setting also functions as an index of a film’s generic status. Chapter 5 will return to the question of setting’s role in genre classification; for the moment, we simply note that particular spaces have become associated with certain film genres rather than with others. When Sergio Leone’s For a Few Dollars More (1965) opens with an extreme long shot of rocky desert terrain, the spectator can make a reasonable, if still tentative assumption that the film is a western (albeit one that proves to have a playful relationship to the western’s conventions as codified by Hollywood). The fact that in this scene we also observe a lone horseman, looking insignificant against immensities of sand and sky, alerts us to another basic function of setting in narrative cinema: its revelatory power with respect to character. As well as serving in quite obvious ways to specify the geographical co-ordinates and socio-economic positioning of film protagonists, settings may also work more subtly to evoke their psychological condition. Such symbolic use of space is especially vivid in German Expressionist cinema, which flourished after World War I. To take just one example: when the vampiric protagonist in F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922) is seen in one shot standing behind the latticed window of an apartment block, we learn not just matter-of-factly about his living arrangements, but, more profoundly, of his sense of incarceration by conformist Weimar society. While highly developed spatial symbolism is a signature of this particular cinematic tradition, the spectator should also be sensitive to expressionistic settings elsewhere in film.

Props

Setting’s functions of substantiating narrative, signalling genre and revealing character are also performed by props: objects of whatever dimensions that appear on screen. Like particular spaces, certain props are correlated with some genres more than with others (again a topic for development in Chapter 5). If a parachute appears on screen, it is a fair bet we are not watching a western (unless of a surreal sort); if a cigarette flares atmospherically into life in close-up, the film noir fan is liable to experience a greater thrill of anticipation than the devotee of epic. And, like settings, props also perform an informational role in narrative cinema with respect to character. Sometimes this function will be limited to confirming socio-economic and occupational status (a reporter’s notebook, a businessman’s briefcase); elsewhere, however, props may take on expressionistic power. When Travis Bickle drops an Alka-Seltzer into water in Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976), the fizzing tablet seems not just one tiny component of his material world but indicative of his synaptic disturbance to the point of explosion (this effect enhanced by use of extreme close-up and non-naturalistic sound).

Props – or, speaking less technically, things – have also been at the centre of long-running theoretical debates over film’s realism or otherwise as a medium. For key texts in a broadly realist tradition, including André Bazin’s What Is Cinema? (1958–62) and Siegfried Kracauer’s Theory of Film (first published in 1960), cinema shares with photography a vocation to reveal with heightened vividness the material world that we inhabit. From this perspective, the chief value of showing a cigarette or a parachute is to represent it in all its detailed particularity (a vision which, to be sure, may surpass that of everyday eyesight because of the camera’s capacity for close-up). Yet for writers from other theoretical positions, cinema valuably frees objects like these from their material circumstantiality and instead endows them with other, non-realist potentialities. Luis Buñuel deplores the fact that for Italian neo-realists – favourite filmmakers, not coincidentally, of Bazin and Kracauer – ‘a glass is a glass and nothing more’ (Hammond, 2000: 115). In his 1918 essay ‘On Décor’, the French Surrealist author Louis Aragon positively revels in the elusive and multiple significances of film props: ‘on the screen objects that were a few moments ago sticks of furniture or books of cloakroom tickets are transformed to the point where they take on menacing or enigmatic meanings’ (Hammond, 2000: 52).

In thinking about the use of props in film, there is no need to be committed exclusively to either of these opposing perspectives. Depending on context, exactly the same object on screen may be a thing valued for its concrete particularities, or its narrative suggestiveness, or its symbolic density. ‘Sometimes’, as Freud is famously said to have remarked, ‘a cigar is just a cigar’; at other times, though, it may be more or other than this (a phallic symbol, most obviously). The television set that ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- Preface to the second edition

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Seeing film: mise-en-scène

- 2 Film editing: theories and histories

- 3 Hearing film: sound and music

- 4 Film and narrative

- 5 Film and genre

- 6 Film and authorship

- 7 Star studies

- 8 Film and ideology

- 9 Film industries

- 10 Film consumption

- Conclusion: film studies and the digital

- Further reading

- Online resources

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Beginning film studies by Andrew Dix in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Gothic, Romance, & Horror Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.