- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Analyses the experiences of Spanish Republican refugees in France

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Introduction

Coming to terms with the Spanish republican exile in France

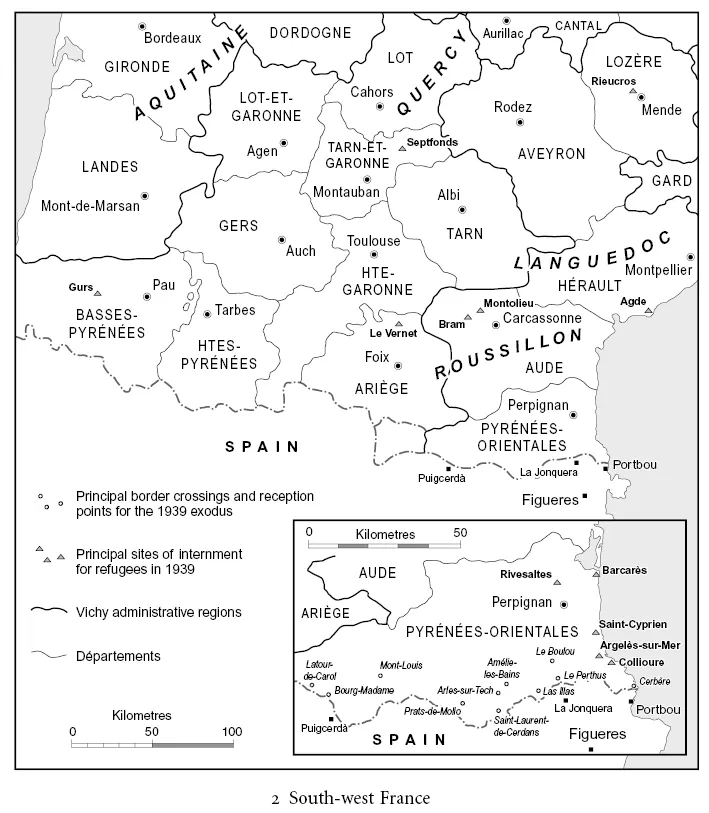

Miguel Oviedo could not have anticipated the extent of exclusion and uncertainty awaiting him as he trudged over the border into France at 11.30 a.m. on Monday 6 February 1939. According to the French government everything was in place for the arrival of the Spanish republican refugees. But in the small village of Argelès-sur-Mer the local authorities had barely any time to react to events, managing to do little more than erect a barbed-wire enclosure on the nearby beach to keep the refugees apart from the local population. Photographs taken at the time show an enormous expanse of windswept beach with refugees attempting to gain some protection from the elements under makeshift bivouacs and in holes dug from the sand. Miguel set foot in the camp on Tuesday evening. Food was out of the question; the queues were enormous. Fortunately some war-wounded refugees offered him space in one of the rare barracks. Even so, Miguel's diary entry for that day presents a sense of foreboding as it closes with the words: ‘under these conditions we won't last for long’.1

The French state was already well versed in providing refuge for persecuted peoples from across the European continent, and therefore could have received the Spanish republicans more humanely. But refugees' rights had substantially deteriorated towards the end of the 1930s as successive governments battled against a gloomy economic outlook, deepening divisions in French society, a crisis of national identity and an increasing prospect of war with Germany. More specifically, Édouard Daladier's Radical-led government set out to limit any further refugees from settling in the country by transforming France from a refuge to a place of transit: a temporary rather than a permanent place of asylum. The start of 1939 was clearly not an auspicious time for the reception of close to half a million refugees from the Spanish Civil War.

The very particular circumstances surrounding the French government's reception policy – involving the forced separation of families and friends and the ensuing internment of hundreds of thousands of people – represents a unique episode in French refugee history: never before had the country experienced a rapid influx of refugees of this magnitude; and never before had the French state responded to the call for asylum with mass internment. Admittedly, one can cite other occasions in the twentieth century when the French state placed refugees in camps during peacetime: the Armenians in the 1920s and the Harkis in the 1960s. But even so, in both cases the camps were conceived more as accommodation centres as opposed to places of internment. Neither before nor after have the French authorities and public – especially in the south-west of the country – reacted with such intensity to the reception of a group of refugees.

The staggering mass of French official documents produced in response to the Spanish refugees' arrival is a further and telling indicator of the exceptional circumstances marking the onset of the Spanish exile. The mountainous paperwork was not simply generated because of the scale of the refugee phenomenon. It reflected a level of administrative preoccupation and discrimination which bordered on the obsessive. Even after the repatriation of around two-thirds of the refugees during 1939–40, local French authorities persistently focused on the remaining Spanish republicans. This continued throughout the trails of war with Germany and the subsequent occupation of the country. Although the Liberation involved a readjustment in French perceptions of the Spanish republican exile, the onset of the Cold War was accompanied by a partial return to a vocabulary of discrimination in local authority correspondence.

However, the impact of the Spanish republicans in France cannot be gauged through the optic of French administrative correspondence alone. The modest stele on a tucked-away parcel of land outside Argelès-sur-Mer, which marks the graves of refugees who died whilst interned by the French authorities, contrasts markedly with the striking statue of the Spanish guerrilla-resistance fighter at Prayols in the Ariège. Similarly, the annual commemorations organised by local associations with the participation of local French representatives offer a different, albeit overlapping, perspective from the rituals and objects found in the homes of former refugees in France. Memorials, as well as annual and everyday forms of remembrance, are equally valid traces of a rich and varied history.

This book is about the conditions, and more specifically about the events and processes, which gave shape to the history and memory of one of the most significant exiles in French asylum history. I examine the origins and development of the Spanish republican exile as lived experience and as a subject of remembrance from 1939 to the 70th anniversary in 2009. Given that experience and patterns of remembrance are socially and culturally mediated, I attend to how the processes of mediation unfolded. I therefore privilege an interpretation of exile as a social construction grounded in the actions of both the Spanish refugees, and the institutions and people with whom they interacted in France. This focus furthers historical understanding of refugee history in France more generally and the Spanish republican exile more specifically.

In relation to the wider history of refugees in France, this study makes several contributions. First, I engage with historians' debates over refugees' rights under the Third Republic by rejecting a view of the decade as involving a linear narrative of steadily decreasing rights. While there can be no doubting the brutal consequences of the Daladier government's legislation on the arriving Spanish republicans or the coercion on them to return to Spain, I also explore the opportunities generated by the French war economy of 1939–40. Secondly, while I point towards some aspects of continuity between the Third Republic and Vichy labour strategies for refugees, there is no intent to read the last years of the Third Republic through the prism of Vichy France. On the contrary, the presence of the German authorities in France created an entirely new dynamic which produced a range of unexpected possibilities for those Spanish refugees prepared to negotiate the contradictions in French and German labour policy. Thirdly, I present a more complex and yet telling reading of Resistance narratives in post-Liberation France. The presence of Spanish republicans in local commemorations of the Liberation challenges the view of France being dominated by the Gaullist and Communist national visions of the Resistance heritage, while also revealing the origins of the current commemorative culture of the Spanish republican exile.

The analysis of Spanish republicans' life histories and remembrance practices adds another dimension to studies of refugees in France. We discover how the painful experience of forced relocation was immensely aggravated through the French government's reception strategy, which in turn created a long-standing lens through which Spanish republicans interpreted and subsequently recalled their lives in France. Because history and memory have often been conceived of as separate phenomena, historians have yet to explore fully the Spanish republicans' commemorative practices. This book redresses this neglect by recognising the symbiotic relationship between memories of the past and experiences of the present which characterised the long and uneven development of a commemorative culture of exile in France. Attention to both the public and private spaces of remembrance produces evidence which suggests the need for an alternative reading of Pierre Nora's concept of realms of memory. Nora's contention that ‘there are realms of memory because there are no longer memory environments’ carries little weight for refugees deprived of the institutions and cultural apparatus needed for the production of realms of memory and who arrived in France with little more than, and in some cases not even, a suitcase.2 In a context when daily rituals and everyday objects became important vectors for remembering, is it not more appropriate to reverse Nora's maxim: ‘were there memory environments because there were no longer any realms of memory’?

The discussion of remembrance does not imply that Spanish republicans were entrenched in the past. On the contrary, this book eschews any view of exile as engendering nostalgia and paralysis through an obsession with the past and returning to Spain. Instead, I adopt an interpretation which accounts for the role of historical contingency and the enabling properties of remembrance. In respect of this latter point, Spanish republicans' recollections were more frequently mobilised as a strategy for responding to contemporary and future concerns. Whether it is in relation to the paths trodden over the Pyrenees and across the south-west of France or to the array of restraints, opportunities, choices and motivations that characterised refugees' lives as they interacted with the institutions and citizens of France, the notion of trajectory is important. The temporal, spatial and social-interaction emphasis of this study is reflected in its title The routes to exile which adopts Paul Gilroy's use of ‘routes’ as a homonym of ‘roots’.3

Searching for the Spanish republican exile in France

If we were to speak of a ce...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series page

- Title page

- Copyright

- Preface

- List of abbreviations

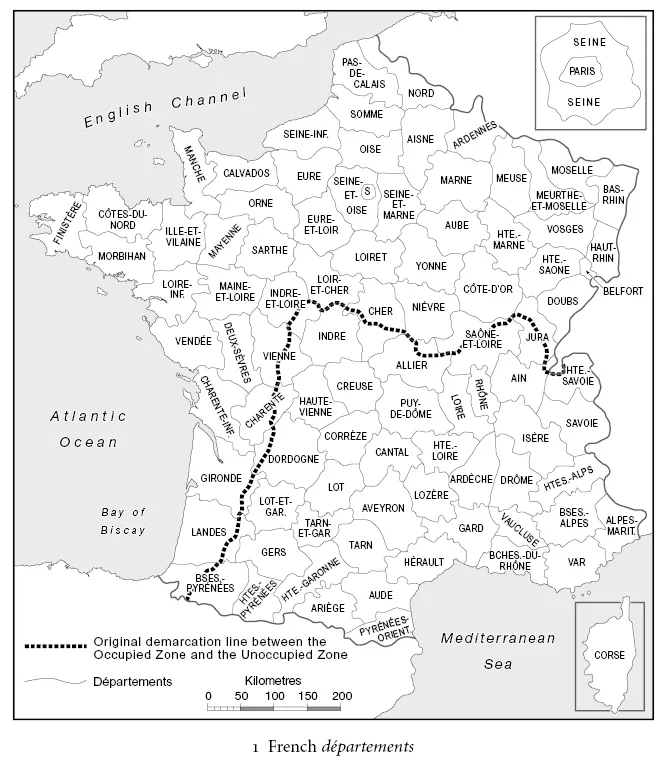

- Map 1 French départements

- Map 2 South-west France

- Introduction

- Part I: The onset of exile

- Part II: Working in from the margins

- Part III: Aspirations of return, commemoration and home

- Appendix

- Conclusion: trajectories and legacies

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The routes to exile by Scott Soo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Social History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.