![]()

Part I

Scandinavia past and present

![]()

1

The eight quills of the swan

An eagle sometimes flies low but a hen never reaches any great heights.

(Virolainen 1969: 469)

So read the postscript of a letter which, citing from Lenin, was sent by an indignant communist in Helsinki to the Finnish prime minister Johannes Virolainen. It was in response to a circular which the premier believed would market the government’s performance to voters in the capital city in the long run-up to the 1966 general election. We are left in no doubt about who the hen is, or, indeed, about the prime minister’s ability to see the humorous side of things! This chapter, however, is not about eagles, still less hens; rather, it focuses on a particular swan – the eight-quilled swan of Nordic co-operation depicted in the logo of the Nordic Council and representing the five nation states of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden, and the three Home Rule territories of the Faeroes, Greenland and Åland. It offers a broad introduction to the (changing) geo-politics of the Nordic region and views co-operation and, more frequently in an historical light, conflict between the member states in a longitudinal perspective. There were times when relations between the Nordic countries fell very much into the ‘ugly duckling’ category and the prospect of sustained solidarity of purpose in Norden seemed remote.

History divides the Nordic region in two: the former imperial states and the twentieth-century successor states. Denmark and Sweden fall into the former category. Denmark was undoubtedly the driving force in the region from the late fourteenth century to the early sixteenth. Thus the Danish and Norwegian monarchies were united in 1380 (Denmark acquired Iceland in the process) and Norway was incorporated into Denmark in 1536. Moreover, Denmark dominated the Kalmar Union of the three Scandinavian kingdoms of Denmark–Norway and Sweden between 1397 and 1523. Norway remained part of Denmark until 1814, when, as a by-product of the Napoleonic Wars, it passed to Sweden, although Iceland was linked with the Danish crown until 1944. After Denmark’s heyday, Sweden emerged as the leading light in the region. Indeed, at its prime in the seventeenth century, Sweden was a great power, controlling a multi-ethnic empire in the Baltic. It incorporated areas inhabited by Swedes, Danes, Norwegians, Finns, Lapps, Ingrians, Estonians, Latvians and Germans. Of the successor states, Norway was the first to gain independence from Sweden (to which it had been conjoined in a personal union) following a referendum in 1905. Finland, part of Sweden until 1809 and a Grand Duchy of the czarist Russian empire thereafter, unilaterally declared its independence on 6 December 1917 in the aftermath of the Bolshevik revolution in St Petersburg. Finally, Iceland gained limited self-government in 1874, autonomy in 1904 and independence in a personal union with Denmark in 1918. It became the last of the Nordic states to achieve full independence, following a referendum in 1944.

Some quarter of a century ago Basil Chubb wrote The Government and Politics of Ireland (Chubb 1982) as part of a planned series on small European democracies which was never completed. The five nation states that comprise Norden would have been prime candidates for inclusion. True, there has been a tendency to view the Nordic region as ‘much of a muchness’ – a homogeneous whole ‘up there’, so to speak, which can be treated as one. The Nordic states in short have occasionally suffered from the lack of differentiation inherent in the classic London cabbie’s query: ‘What’s the weather been like abroad?’ Equally, when viewed from both an historical and a contemporary standpoint – that is, through the windows of both the past and the early years of the new millennium – it is clear that the Nordic states have been linked by geography, history and common linguistic bonds and that out of this admixture there has emerged at least a degree of common identity and sense of belonging to the north.

A brief overview of the Nordic region today

In 1980 the Finnish director Risto Jarva produced a delightful allegorical film called The Year of the Hare (Jäniksen vuosi) in which he charts the friendship which develops when a businessman, returning home by car, accidentally injures a hare and follows it into the forest, where he nurses it back to health. When he finally returns to Helsinki, having opted out of the rat-race and lived rough with the hare, his bills are still awaiting him and his wife is less than pleased. Only the hare remains loyal when he is committed to a debtor’s prison! Mention of hares or more particularly rabbits readily brings to mind Giovanni Sartori’s axiomatic assertion in relation to comparative analysis that it is impossible to compare stones and rabbits: we must compare broadly like with like, not least so as to classify different sub-types of the species. What, then, are the prima facie similarities and differences between the Nordic states in the first decade of the new millennium?

An obvious and integral feature has to do with the ‘politics of scale’, since, with the possible exception of Sweden, all the Nordic states may be considered small democracies. Iceland, which in 2007 had a population of 309,699, could, as Gunnar Helgi Kristinsson (1996) has noted, be regarded either as the smallest of the European small states or a relatively large micro-state. In fact, in so far as micro-states not only have very small populations but – as in the case of Andorra, Monaco and San Marino – are also ‘heavily dependent on neighbouring states for diplomatic support’ (Archer and Nugent 2002: 5) and do not have an independent foreign policy, Iceland is best regarded as the smallest of the European small states. It is the only Nordic state never to have applied for membership of the European Community (EC)/European Union (EU) and, distinctively in the region, has a special relationship with the United States through its 1951 Defence Agreement (Thorhallsson 2004).

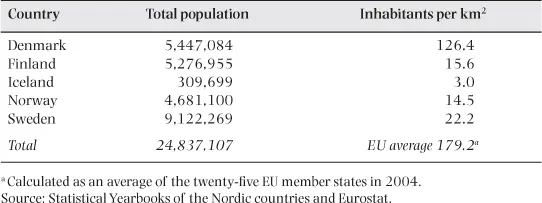

Altogether, the population of Norden today is just under 25 million (table 1.1). Each boasting well over 5 million inhabitants, Denmark and Finland have populations about the same size as that of Scotland, whilst Norway’s is somewhat smaller. With the exception of Denmark, moreover, the Nordic states are relatively sparsely populated. Iceland (3.0 inhabitants per square kilometre), Norway (14.5) and Finland (15.6) are the three countries with the lowest population densities in Europe and there is considerable regional variation within all three. For example, over two-fifths of the total Icelandic population lives in Reykjavík and two-thirds in the capital and its hinterland constituency of Reykjanes. On accession to the EU in 1995, large areas of northern Finland and northern Sweden received special (so-called Objective Six) support from the structural funds, created specifically to accommodate the Nordic newcomers and available in those districts with under eight inhabitants per square kilometre. Even in Denmark, which in 2007 had 126.4 inhabitants per square kilometre, the comparative population density was well under the EU average of 179.2 and that of small states such as Belgium (343.6 in 2003) and the Netherlands (481.9 in 2004).

Table 1.1 The population size and density of the Nordic states in 2007

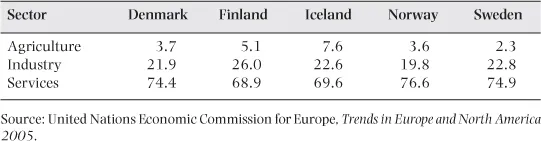

Table 1.2 Total civilian employment in the Nordic states by major economic sectors in 2005 (%)

The smallness of the Nordic democracies, it has been suggested, has permitted the personalisation of relations between the relatively small elite class of politicians and administrators, which in turn has conduced towards pragmatic solutions and compromise politics. Indeed, several writers have characterised the Nordic states as a distinctive sub-type of liberal democracy – ‘consensual democracies’. Others have spoken of a ‘Nordic model’ of government, whilst Sweden in particular has been much admired as the archetype of an advanced welfare state. Similarities in the nature of politics and government in the Nordic states will, of course, be central to the ensuing chapters of this book.

All the Nordic states have been affected by ‘economies of scale’ in the obvious sense that the small size of the domestic market has dictated a strong export orientation and its concomitant, a deep commitment to free trade. In structural terms, the Nordic countries have reached roughly comparable stages of economic development. To put it another way, the Nordic states are typical post-industrial, information-based, service-dominant economies. The proportion engaged in the primary sector has dwindled to under 3 per cent in Sweden and under 10 per cent in Iceland; manufacturing industry employs between one-fifth and just over one-quarter of the labour force across the Nordic region, whilst services average 72.9 per cent (table 1.2).

As small states, linked by geography, a shared history and common linguistic bonds, the Nordic countries readily lend themselves to comparative analysis. Boasting striking structural and behavioural similarities in, among other things, their party systems, electoral choices and patterns of interest group representation, and influencing each other’s developments by means of diffusional impulses – the post-Second World War expansion of the institution of the ombudsman is a notable case in point – the political agenda in the Nordic states often mirrors issues and challenges facing all the member states of the region to varying degrees. There is, moreover, widespread informal inter-governmental consultation in preparing responses to these challenges, as well as formal co-operation at the regional level. Yet the many common denominators should not obscure clear lines of differentiation and demarcation. In short, the Nordic states exhibit important lines of intra-regional variation. They may all be rabbits or stones à la Sartori, but there are distinguishing features.

In the field of domestic politics, there are obvious institutional differences within the Nordic region, most notably the fact that Denmark, Norway and Sweden boast constitutional monarchies whereas Finland and Iceland have directly elected presidents. Constitutional provisions, of course, do not always indicate much about the actual distribution of power; convention is important and so, too, is the influence of political parties. None the less, the existence of dual executives in two of the states of the region suggests the need to explore the historical backdrop of the constitution-building process, as well as the extent to which the balance of power within the executive arm has changed.

In the foreign and security policy area, there has been a clear bifurcation within the Nordic region since the Second World War. Denmark, Norway and Iceland were founder members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), which was formed as the Cold War took hold in 1949. Iceland, in fact, has neither an army of its own nor a secret service. Sweden, in contrast, has championed a position of neutrality since 1814 and Finland, too, aspired to be neutral (principally as a means of maintaining its post-war independence from the Soviet Union) and currently describes its policy as one of military non-alignment. The essential security policy configuration that emerged in the late 1940s came to be known as the ‘Nordic balance’ and reflected the differing needs and interests of a bloc of states that occupied a frontier position between capitalism and communism.

Equally, there have been different responses among the states of the region to the increased pace of European integration. Whilst Denmark since 1973 and Finland and Sweden since 1995 have been full EU members, the Norwegian people have twice (in 1972 and 1994) voted against accession, despite agreements supported by the overwhelming majority of the political elite. The result has been that Norway and indeed Iceland have contented themselves with membership of the European Economic Area (EEA), which came into force in 1994 and which grants access to the EU single market, although excluding sensitive areas such as agricultural, environmental and regional policy. Finnish and Swedish membership has given the EU a Nordic dimension, as well as a common border with Russia.

Finally, in the geo-economic context, all the Nordic economies have been export-led and they have been affected by, and adapted in varying degrees to, the process of globalisation. The Finnish mobile-phone giant Nokia – with a world market share in 2007 of around 36 per cent – is perhaps a limiting case in this respect. Nokia employs over 68,000 people in 120 countries and has production factories in China, India, Germany and, most recently, Romania, in addition to the town of Salo in Finland. Its contribution to the Finnish economy is enormous. Thus, Nokia’s share of total exports (excluding those of its partners) is about one-quarter and the value of its net sales amounts to approximately the same as the annual Finnish budget. Similarly, only four of IKEA’s production factories are in Sweden – accounting for less than one-fifth of total production – the majority being in eastern Europe.

The Nordic states: the ‘other European community’?

Pointing to a common Nordic identity and the complex web of relations between the member states and Home Rule territories in the region, Turner and Nordquist (1982) referred in the early 1980s to ‘the other European community’. Various forms of regional co-operation have evolved, particularly during the twentieth century, when the Nordic states comprised a frontier bloc between fascism and communism between the two World Wars and the pluralist democracies and (Soviet) people’s democracies during the Cold War. Notable, for instance, was the Norden Association (Foreningen NORDEN), which was founded in 1919 and today has over 70,000 members and about 550 local branches across the region. It capitalised on the co-operation between Denmark, Norway and Sweden during the First World War and quickly extended its network of commercial associations, interest groups and individual citizens to Iceland (1922) and Finland (1924). It has traditionally emphasised educational and cultural contacts, whilst among its recent projects has been ‘Hello Norden’, a telephone and Internet service, launched by the Swedish branch of the Norden Association in 2001, which offers advice to Nordic citizens who have ‘got stuck’ in the bureaucracy or need clarification of the regulations when relocating to another Nordic country.

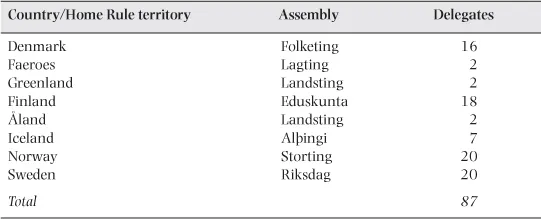

The most notable cross-national achievement, however, has been the Nordic Council (Nordiska Råd), set up on a Danish initiative in 1952 as a forum for inter-parliamentary co-operation. The official symbol of Nordic co-operation is the swan, its eight quills representing the constituent parts of the region – the nation states of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden and the three Home Rule territories of Greenland, the Faeroes and Åland. The last-mentioned trio will be examined in more detailed in the next chapter, on nation-building and state-building in Norden, but warrant the briefest note en passant.

Greenland (Kalaallit Nunaat in the native Inuit language) covers an area of 2 million km2, although only about 342,000 km2 are free from a permanent ice cap. It had a population in 2005 of 56,969 persons, 90 per cent of them Inuit-speaking Eskimos. Inuit means ‘people’. Greenland obtained autonomy within the Danish kingdom in 1979 and three years later voted in a referendum to leave the EC. When it left the EC, Greenland negotiated ‘Overseas and Countries Association’ status, which permits favourable access to European fishing markets, whilst a fishing agreement is renegotiated every five years. Its capital is Nuuk and the official language is Kalaallisut, or West Greenlandic.

The Faeroes (Føroyar) comprise seventeen inhabited islands covering an area of 1,400 km2 with a population in 2003 of 47,700. In 1948 the Faeroes accepted Home Rule status as a self-governing community within the Danish state. Faeroese is the official language and the capital is Torshaven.

Åland (Ahvenanmaa in Finnish) comprises fifty inhabited islands covering a land area of 1,481 km2 and had a population in 2006 of 26,766, 40 per cent of them living in the only town, Mariehamn. Since a League of Nations ruling in 1921, Åland has been an autonomous and demilitarised province of the Finnish Republic. The official language is Swedish.

Table 1.3 The composition of the Nordic Council in 2007

The Nordic Council comprises eighty-seven members nominated by the five national parliaments and the executive bodies of the three autonomous territories (table 1.3). In the Scandinavian languages ting means ‘assembly’, and the Nordic voters thus have ‘tings’ on their mind when they go to the polls in general elections.

Each member of the Nordic Council has a deputy, and the Council holds an annual session, usually in November. The role of the Nordic Council will be considered more fully in chapter 13, but one of its earliest achievements was the creation in 1952 of a passport union, which meant thereafter that trips between Nordic countries did not require a passport. A common labour market treaty in 1954 also enabled people to move freely within the region in search of work without the need for permits, and so on – a development several decades ahead of the achievement of the free movement of labour in the EU. Nordic co-operation was further consolidated in 1971 with the creation of the Nordic Council of Ministers. Each country has a minister of Nordic co-operation. It is important to emphasise that, much like the European Parliament, the Nordic Council is a consultative and advisory body, a...