- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Examines the reasons behind the variation in the electoral fortunes of the West European parties of the extreme right in the period since the late 1970s.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The extreme Right in Western Europe by Elisabeth Carter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Diplomacy & Treaties. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Edition

1Subtopic

Diplomacy & Treaties1

The varying electoral fortunes of the West European parties of the extreme right

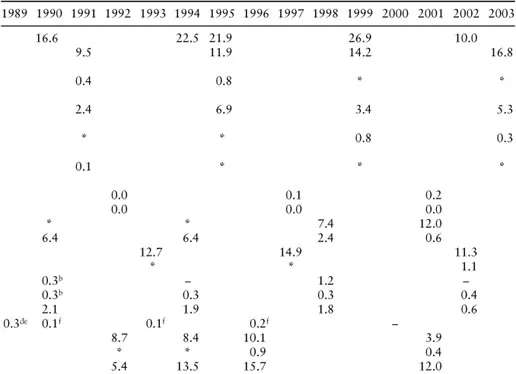

Right-wing extremist parties have experienced a dramatic rise in electoral support in many West European democracies since the late 1970s. One of the most prominent such parties, the French Front National (FN), won nearly 10 percent of the vote in both the 1986 and 1988 national legislative contests, and in 1993 and 1997 its share of the ballots grew even further, first to 12.7 percent and then to 14.9 percent. Similarly, in Austria, the Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) recorded close to 10 percent of the vote in 1986, and then saw its electoral score rise first to 16.6 percent in 1990, then to 22.5 percent in 1994, and then to a massive 26.9 percent in 1999. The Vlaams Blok (VB) has also performed well at the polls in this time period, recently securing over 16 percent of the vote in Flanders. In Scandinavia, the Fremskridtspartiet (FRPd) and the Fremskrittspartiet (FRPn) (Danish and Norwegian Progress Parties) have received over 10 percent of the vote on a number of occasions since the late 1970s, and the Dansk Folkeparti (DF) has also been successful at the polls since its foundation in 1995. Likewise, in Italy, the Alleanza Nazionale (AN) and the Lega Nord (LN) have both secured vote shares of over 10 percent in a number of elections since the early 1990s.

By the mid-1990s some of these parties had acquired sufficient electoral strength to become relevant players in the formation of governmental majorities. In Italy, the AN and the LN both entered office in 1994, as junior partners in Silvio Berlusconi’s first government, and in 2001 they once again formed part of the governing coalition when the alliance with Forza Italia was renewed. In a move that sparked widespread international criticism, the Austrian FPÖ also assumed office when it entered into coalition with the Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) in 1999. The party remained in government after the 2002 elections when the ÖVP-FPÖ coalition continued. In Norway and in Denmark, right-wing extremist parties similarly play a role in the formation of parliamentary majorities. Although they do not form part of the governing coalition, since the elections of 2001, both the Norwegian FPRn and the Danish DF have periodically lent their support to the minority bourgeois governments.

The considerable attention that these more successful right-wing extremist parties have received both in the media and in the academic literature has sometimes obscured the fact that parties of the extreme right have not been successful at the polls in all West European countries, however. Indeed, looking at Table 1.1, which documents the electoral scores of all the parties of the extreme right in Western Europe in the period since the late 1970s, it is clear that, alongside the successful parties mentioned above, there are a number of other parties that have experienced relative electoral failure. The German parties of the extreme right, for example, have remained electorally unsuccessful over this period. Even at their peak in 1990, the Republikaner only managed to secure 2.1 percent of the national vote. In the Netherlands, too, the extreme right has remained marginalized. The Centrumdemocraten (CD) polled only 2.5 percent of the vote at their height in 1994. In Greece, in Portugal and in Spain the parties of the extreme right have been similarly unsuccessful at the polls, while in Britain they have performed even more poorly. The National Front (NF) won a mere 0.7 percent of the vote in 1979 and has never managed to secure more than 0.1 percent of the vote since then, and the British National Party (BNP) has never recorded more than 0.2 percent of the national vote.

In addition to varying across countries, the electoral scores of individual parties of the extreme right have varied over time. It has been quite common for the same party to record low electoral scores in one election but to secure high electoral scores in another. For instance, as Table 1.1 illustrates, in 1983 the Austrian FPÖ polled only 5 percent of the vote. Yet in 1999 its vote soared to 26.9 percent. It then fell again in 2002, to 10.0 percent. Similarly, in Italy the Movimeto Sociale Italiano (MSI) recorded a mere 5.3 percent of the vote in 1979, but in 1996 (under the new guise of the AN) its vote stood at 15.7 percent. In the same way, in Norway, the FRPn polled only 3.7 percent of the vote in 1985, but secured 15.3 percent of the vote in 1997. In contrast, the Danish FRPd won 11.0 percent of the vote in 1979, but in 2001 its vote was only 0.6 percent.

Whereas the electoral breakthrough and the subsequent progress of the more successful parties of the extreme right have been extensively analysed in the existing academic literature, the issue of the variation in the electoral scores of the right-wing extremist parties across Western Europe has received only limited attention. In other words, while numerous studies exist that illustrate and help account for the rise of right-wing extremism, there are few analyses that seek to explain the reasons for the uneven electoral success of the West European parties of the extreme right.

Accounting for variation in the extreme right party vote

This book examines this question of the variation in the right-wing extremist party vote across Western Europe in a comprehensive and comparative manner. Drawing on the few existing studies that have already explored this issue, it investigates a broad set of political, supply-side reasons why the electoral scores of the West European parties of the extreme right have varied so considerably since the late 1970s. More specifically it explores whether the disparity in the electoral fortunes of the parties of the extreme right can be explained, to some extent, by the fact that the parties embrace different types of right-wing extremist ideology, and by the fact that they have different forms of party organization and leadership. It also investigates whether the varying vote scores of the parties of the extreme right can be accounted for, in part at least, by the different patterns of party competition at work in each of the party systems in which the right-wing extremist parties operate, and by the different institutional environments present in each of the countries in which the parties compete.

These are the factors that have tended to be overlooked in the wider literature on right-wing extremism. Indeed, the majority of existing studies have focused on demand-side explanations for the rise of right-wing extremism, which concentrate on the socio-demographic characteristics and attitudes of right-wing extremist voters, and the effects that socio-economic change has had on this section of the electorate. Among these demand-side explanations, different studies have emphasized the rise of immigration, the growth of voter dissatisfaction with the established political parties and/or democratic system, the breakdown of social ties and the resultant feelings of insecurity and anomie, the calls for a return to more traditional and paternalistic modes of social organization, and the rise of social deprivation and exclusion.1 Supply-side explanations for the growth of right-wing extremism, which focus on the supply of extreme right alternatives, and which examine the parties of the extreme right as strategic actors attempting to best respond their political and institutional environments, have, by contrast, received much less attention.2

The prevalence of demand-side explanations for the rise of right-wing extremism has also meant that while the social and economic reasons for the growth of this phenomenon have been well discussed and documented, the influence of political factors on the fortunes of the parties of the extreme right has attracted less coverage. Political explanations have remained rather under-researched, especially in the comparative perspective. Furthermore, there has been a tendency for these explanations to be characterized by assumption, rather than by fact and empirical analysis. It has often been claimed, for example, that right-wing extremism has been allowed to flourish in countries that employ proportional electoral systems (Hermens, 1941; Hain, 1986), and yet there is little empirical analysis that supports this assertion.

A further reason why this study focuses on political explanations for the uneven electoral success of the right-wing extremist parties is that while social and economic factors are important in explaining the rise of right-wing extremism as a general phenomenon, and are also crucial in accounting for individual voting decisions, they help little in understanding why some parties of the extreme right have fared better at the ballot box than others. At the aggregate level at least, little difference exists in the socio-economic make-up of the countries under investigation, and so there is little reason to expect aggregate levels of social and value change to differ significantly across these countries. It is therefore unlikely that the pronounced variation in the right-wing extremist parties’ electoral fortunes will be explained satisfactorily by different levels of social and value change.

Table 1.1 Electoral scores of the West European parties of the extreme right, 1979–2003 (%)

By focusing squarely on the political explanations for the disparity in the electoral fortunes of the parties of the extreme right, this study does not examine the influence of culture or history on the right-wing extremist party vote. Though clearly of importance in an overall account of the variation in the electoral scores of the parties of the extreme right, cultural and historical explanations are notoriously difficult to operationalize and test, especially in a comparative perspective. Even at the level of a single-country case study there is little agreement over the factors that should be included in such explanations.

Four sets of political, supply-side explanations for the disparity in the electoral fortunes of the West European parties of the extreme right are put forward, examined and tested in the course of this book. In the first instance it investigates the ideologies of the different right-wing extremist parties, since, regardless of the nature of the institutional and political environments in which the parties find themselves, the electoral fortunes of the parties of the extreme right may depend, to a certain extent, on the nature of the message and policies that they put forward. Rather than there being a uniform right-wing extremist ideology, the ideas and policies of the different parties vary quite considerably, with some of these being more popular with electorates than others. Consequently, it is quite possible that the variation in the electoral success of the parties of the extreme right across Western Europe may be partly explained by the presence of different ideologies, with the more successful right-wing extremist parties embracing one type of ideology and the less successful ones adopting another.

The electoral fortunes of the parties of the extreme right are also likely to be affected by the parties’ internal organization and leadership, and by the consequences of these internal dynamics. In fact, a general consensus in the literature on right-wing extremist parties suggests that ‘one of the most important determinants of success is party organization’ (Betz, 1998a: 9). More specifically, right-wing extremist parties with strong, charismatic leaders, centralized organizational structures and efficient mechanisms for enforcing party discipline are likely to perform better at the polls than parties with weaker and uncharismatic leaderships, less centralized internal structures and lower levels of party discipline. The former parties are expected to exhibit greater internal cohesion, and thus greater levels of programmatic and electoral coherence. In turn, these attributes are expected to enhance the parties’ credibility and result in higher levels of electoral success.

In addition to being influenced by party-centric factors, the electoral fortunes of the parties of the extreme right are likely to be affected by party system factors. In particular, they are expected to be influenced by the patterns of party competition in the party system. On the one hand, the dynamics of party competition on the right side of the political spectrum are likely to be important in explaining the variation in the right-wing extremist party vote. The ideological proximity of the parties of the mainstream right (the extreme right parties’ nearest competitors) determines how much political space is available to the parties of the extreme right, and this space may well be related to how successful the extreme right parties are at the polls. Furthermore, the electoral fortunes of the right-wing extremist parties may also depend on the positions that these parties choose to adopt for themselves within the political space available to them. On the other hand, the patterns of party competition at the centre of the political spectrum are also likely to influence how well the parties of the extreme right perform at the polls. In other words, the degree of ideological convergence between the mainstream right and the mainstream left may well affect the right-wing extremist party vote.

As well as being influenced by the dynamics of the party system in which they compete, right-wing extremist parties are also conditioned to a greater or lesser extent by the ‘rules of the game’ of the political system in which they operate. More specifically, the right-wing extremist party vote is likely to be influenced by the proportionality of the electoral systems in operation in the countries in which they compete, and by the broader electoral laws governing how parties and candidates may gain access to the ballot, to the broadcast media and to state subventions.

By considering this broad range of factors the book presents a comprehensive examination of the political, supply-side factors that may influence the electoral scores of the parties of the extreme right across Western Europe. This contrasts with the analyses carried out in the existing studies that have examined the issue of variation in the right-wing extremist party vote at the macro (rather than the voter) level. While between them these analyses have identified and tested many of the factors that help explain the uneven electoral fortunes of the parties of the extreme right, individually the existing studies have chosen to concentrate on sub-sets of explanations and have thus focused on only some of the possible reasons why the parties of the extreme right across Western Europe have recorded such divergent electoral results. For example, Jackman and Volpert’s analysis (1996) examines the influence of the political and economic environment on the right-wing extremist party vote, but does not investigate the effects that party-centric factors such as ideology and organization have on the electoral fortunes of the parties of the extreme right. By contrast, the studies by Ignazi (1992, 1997a), Betz (1993b, 1994) and Mudde (2000) concentrate on party ideology, and the study by Taggart (1995) examines party ideology and party organization, but they do not consider how party system factors and electoral institutions affect the right-wing extremist party vote.

Even the more comprehensive of the existing studies do not consider all the supply-side factors that may affect the right-wing extremist party vote. Golder (2003a, 2003b) investigates the influence of electoral systems, and the effect of the level of unemployment and immigration on the electoral scores of the parties of the extreme right, for example, but does not examine the influence of party system factors. Similarly, Kitschelt (1995) suggests that party ideology and party organization are important factors in explaining the variation in the right-wing extremist party vote, and also points to the impact of party system factors as well as to the influence of individual-level variables such as voters’ social characteristics and attitudes, but he does not consider the effects of electoral institutions. Likewise, Lubbers et al. (2002) consider a whole host of variables (including individual-level ones) that may affect the vote scores of the parties of the extreme right, but do not take into account the impact of party ideology or the influence of electoral institutions on the right-wing extremist party vote.

In addition to offering a comprehensive coverage of the political, supply-side factors that may help explain the uneven electoral success of the parties of the extreme right, this analysis builds on the existing studies by offering substance for the different explanations for the variation in the right-wing extremist party vote. With the exception of the work by Kitschelt, all the existing studies mentioned above are journal articles, which test the various hypotheses by way of integrated statistical models. They therefore contain limited information on the individual right-wing extremist parties and provide no detailed coverage of the national contexts in which these parties compete. This analysis, by contrast, is able to examine the different factors that affect the right-wing extremist party vote in significant detail, and to investigate the individual parties and their national contexts in considerable depth.

Right-wing extremist parties in Western Europe since 1979

All right-wing extremist parties that have contested elections at the national level are included in this study, regardless of their size.3 The analysis examines 40 right-wing extremist parties across 14 countries (see Table 1.1). This considerably exceeds the number of parties and countries examined in some of the existing studies, and means that the conclusions reached throughout this analysis provide a sound base for generalization.

As a result of the inclusive approach adopted in this book, a number of parties that have been omitted from some other studies of the extreme right are examined here. The Italian LN, for example, is included in this study even though it has sometimes been considere...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of tables and figures

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations: right-wing extremist parties

- 1 The varying electoral fortunes of the West European parties of the extreme right

- 2 Party ideology

- 3 Party organization and leadership

- 4 Party competition

- 5 The institutional environment

- 6 Accounting for varying electoral fortunes

- Appendix A: The ideological positions of West European political parties

- Appendix B: The political space in the different countries of Western Europe

- Appendix C: The disproportionality of elections, 1979–2003

- Bibliography

- Index