![]() Part I: Identities

Part I: Identities![]()

1 The common bond

The merging of personal and group identities with specific places, whether they are family homes, neighborhoods or cities, is one of the most commonly accepted yet profoundly significant expressions of the extended self. Yet for all the attention it has received over the years from both design professionals and academic researchers of diverse backgrounds, the source of these ties remains a mystery, only partially resolved according to the interests of whichever profession or discipline is concerned.

The chapter begins with an examination of the meaning of place-identity as interpreted from different viewpoints, including those of ordinary home-dwellers, academics, literary figures and architectural critics and theorists. The marked differences in the meanings attached to spaces and places by both inhabitants and observers lead in turn to a discussion of cultural relativism, as argued by prominent linguists and anthropologists. The early influence of Martin Heidegger’s phenomenology on the idea of place in architectural theory is also discussed, paving the way for an overview of related approaches by later theorists. Other recurring subjects described in the research on the cognition of place are the mental ‘images’ or ‘maps’ revealing the way individuals and groups assimilate the spaces they inhabit, including whole districts – concepts that are further developed in the writings and researches reported in the following two chapters. The anthropologist Edward Hall’s theory of ‘proxemics’1 is also outlined, pointing toward later developments on the subject of mind–body extensions. The chapter concludes with a summary overview of recent studies aimed at reassessing the meaning and significance of place in philosophical and cultural discourses, together with some current debates on identity formation in the modern world as seen by human geographers.

Place-identity

There are as many interpretations of place-identity as there are approaches to the subject. ‘Sense of place,’ ‘genius loci,’ and ‘spirit of the place’ are commonly used terms that describe much the same idea, though the meaning varies according to context and profession. For environmental psychologists like Maxine Wolfe and Harold Proshansky,2 place-identity is inextricably linked with personal identity:

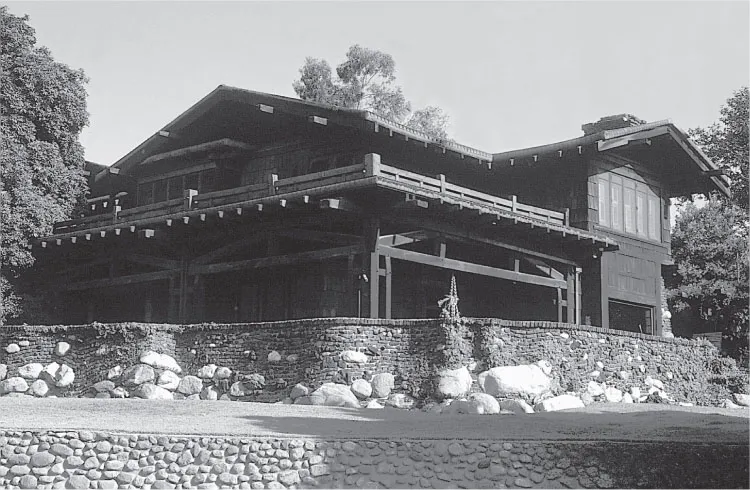

1.1 House on the outskirts of Sydney, by Glenn Murcutt, 1983

The self-identity of every individual has elements of place in it – or as we have said elsewhere, all individuals have a ‘place-identity.’ They remember, are familiar with, like, and indeed achieve recognition, status, or occupational satisfactions from certain places. Whether we are talking about ‘the family home,’ ‘the old hangout,’ ‘my town,’ or some other place, it should be obvious that physical settings are also internalized elements of human self-identity.3

Award-winning designers like the Australian architect Glenn Murcutt have also captured people’s imagination with iconic houses carefully set into the landscape (fig. 1.1).4 In such cases, as with the earlier houses by Greene & Greene in the suburbs of Los Angeles (fig. 1.2),5 the work of some specially gifted architects may come to represent, if only for a limited period, not only an idealized form of dwelling, but a sense of place and preferred way of life for a whole country: the ‘Great Australian Dream’ as it is known in the former case, or the ‘Great American Dream’ in the latter. In either case, the dwelling type and the dream are basically alike, which says much for the similarity between the two cultures.

Even the most ordinary suburban home can evoke strong responses in its present or former occupants, whatever the building looks like, so long as it has the requisite features of the type: functional and comfortable rooms sufficient for all the family; a substantial garden or backyard, a garage and so on (fig. 1.3). In her essay ‘The House as Symbol of the Self,’ Clare Cooper6 finds a deeper explanation in Carl Jung’s concept of archetypes for the importance people attach to their homes and their consequent resistance to any change of customary habitats:

1.2 Irwin House, Pasadena, Los Angeles, by Greene & Greene, 1906, set the style for the popular California bungalow

If there is some validity to the notion of house-as-self, it goes part of the way to explain why for most people their house is so sacred and why they so strongly resist a change in the basic form which they and their fathers and their father’s fathers have lived in since the dawn of time. Jung recognised that the more archaic and universal the archetype made manifest in the symbol, the more universal and unchanging the symbol itself. Since self must be an archetype as universal and almost as archaic as man himself, this may explain the universality of its symbolic form, the house, and the extreme resistance of most people to any change in its basic form [added emphasis].7

Quoting a touching poem about a suburban family home written by a 12-year-old, Cooper also ventures that children, not having yet been socialized into thinking of themselves as individual beings separate from their physical habitat, are generally more sensitive than adults to its value in their lives:

O JOYOUS HOUSE

When I walk home from school,

I see many houses

Many houses down many streets.

1.3 Idealized image of conventional suburban home

They are warm comfortable houses

But other people’s houses

I pass without much notice

Then as I walk farther, farther

I see a house, the house.

It springs up with a jerk

That speeds my pace;

I lurch forward

Longing makes me happy,

I bubble inside.

It’s my house.8

As common as such bonds are, except for a few writers like Cooper,9 architectural critics have generally been slow to acknowledge their strength or meaning. Typically, the Australian architect and polemicist Robin Boyd10 lampooned suburban aesthetic styles and tastes in Australia in the 1950s and ’60s, including the imported and much admired ‘California bungalow’ (figs 1.4, 1.5).11 Nevertheless, Boyd, a pioneering modernist and inventive designer, never actually challenged the detached family dwelling type itself or the suburban pattern it generated, recognizing how deeply rooted they were in Australian culture. ‘Australia is the small house,’ he wrote,12 and he designed many such dwellings himself in the modernist manner he propagated.

Other critics, especially in Europe, launched their own attacks on suburban aesthetics during the same period,13 but like Boyd had no effect whatsoever on the popularity or appearance of suburban homes. Dismissing such reactions as irrelevant to the people who actually live in suburbia, the American sociologist Herbert Gans14 argued that, far from suburbia being the social and cultural wasteland depicted by its detractors, suburbanites enjoy a full social life with their neighbors, who share the same family-centered values and lifestyles. Postmodern critics like Charles Jencks15 and artists like the Australian painter Howard Arkley16 have also accepted and even celebrated suburban aesthetics. From I Love Lucy onwards, countless television sit-coms confirmed the continuing popularity and deep cultural roots of the suburban lifestyle, inviting viewers into their studio-sized but otherwise ordinary-looking living rooms to share the tastes and day-to-day antics and problems of their favorite families on-screen.

1.4 A typical California bungalow in the suburbs of Wollongong, New South Wales, Australia

1.5 A typical California bungalow in the suburbs of Los Angeles

Cities often exert a similar hold on individuals, both in fiction and in real life. James Joyce, a voluntary exile in continental Europe for most of his life, evokes a powerful sense of place in his novel Ulysses, which follows Leopold Bloom and other characters through the real streets and alleyways of the Dublin of his time.17 The novel testifies to the enduring impression Joyce’s early years in the city had on his consciousness, despite his rejection of the conservative culture of his native land and his later decision to move to Paris, where he found equally memorable surroundings. While Ulysses was a unique achievement in many other respects, Joyce was not alone in capturing the essence of a city between the pages of a novel. In her study of the city in literature, Diana Festa-McCormick18 analyses the pivotal role played by major cities in 10 novels by different authors, including Honoré de Balzac and Émile Zola (Paris), Marcel Proust (Venice), Lawrence Durrell (Alexandria) and John Dos Passos (Manhattan). Most authors, she explains, express ambivalent attitudes toward the cities in their novels, acknowledging their darker aspects, including ubiquitous poverty, corruption and injustice, as well as their capacity to inspire. In every case, however, the city is presented as an enduring, dynamic force – a protagonist in itself – shaping and directing the lives of the characters in their novels as much as, if not more than, the other characters around them:

The city often is a catalyst, or a springboard, from which visions emerge that delve into existences unimaginable elsewhere. The city there acts as a force in man’s universe; it is a constant element, immutable in its way while constantly renewing itself. It serves as a repository for miseries, hardships, and frustrations, but also for ever-renascent hopes.19

Joseph Luzzi, a devoted scholar and teacher of the work of Dante, offers a brief but still more eloquent example in literature of the sway a city can have on an individual life. Following the sudden death of his wife in a car accident, Luzzi found echoes of his personal grief in Dante’s epic poem Divine Comedy, where the author describes his own profound grief at having been exiled for the rest of his life from his beloved Florence: ‘You will leave behind everything you love / most dearly, and this is the arrow / the bow of exile first lets fly.’20

Place in architectural theory

Among architectural theorists, Christian Norberg-Schulz has done much to focus attention on the nature of place-identity and its psychic roots. In Genius Loci,21 he attributes his phenomenological approach to the philosophy of Martin Heidegger and to the 1971 collection of essays on language and aesthetics, Poetry, Language, Thought 22 in particular. In a widely quoted essay from that collection, ‘Building Dwelling Thinking,’ Heidegger argues that ‘building’ and ‘dwelling’ have an older and far deeper significance beyond their common meanings as activities or a form of habitable shelter:

What then, does Bauen, building, mean? The Old English and High German word for building, buan, means to dwell. This signifies, to remain, to stay in a place. The real meaning of the verb, bauen, namely, to dwell, has been lost to us […]. The way in which you are and I am, the manner in which we humans are on the earth, is Buan, dwelling. To be a human being means to be on earth as a mortal. It means to dwell.23

Accordingly, for Heidegger, to build or to dwell implies a fundamental act of engagement with the land we live upon. While habitable buildings as we commonly know them are included within the scope of Heidegger’s meaning, he also includes any form of human activity or construction, like a bridge, that modifies the landscape and reflects our presence within it:

[The bridge] does not just connect banks that are already there […]. It brings stream and bank and land into each other’s neighbourhood. The bridge gathers the earth as landscape around the stream.24

Elaborating on Heidegger’s concept of dwelling, Norberg-Schulz argues for a broader appreciation of architecture, not just as a practical art fulfilling various social and cultural functions, but as ‘a means to give man an “existential foothold.”’25 Thus, ‘dwelling above all presupposes identification with the environment...