- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

German electoral politics

About this book

The study of German electoral politics has been neglected of late, despite being one of the most pervasive elements of the German political process. Geoffrey Roberts exciting new book argues that concentration on electoral politics facilitates deeper understanding and appreciation of German political system It provides explanations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access German electoral politics by Geoffrey Roberts in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Emigration & Immigration. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Elections, parties and the political system

There are many ways of analysing German politics. Recent studies have, for example, focused on policymaking, on institutions (Helms 2000), and on the interface between German politics and the politics of the European Union (Bulmer, Jeffery and Paterson 2000; Sturm and Pehle 2001). All these approaches are valid, but none captures all the intricate interconnections and multiple dimensions of the political process in Germany. The once-popular focus on electoral politics has been neglected of late, yet it can be asserted that electoral politics is one of the most pervasive elements of the German political process, indeed the bedrock upon which the political system is supported. It is also still an important approach – if not always in the ways in which it is important in other European democracies such as the United Kingdom or France. In this book, the case is made for retaining some degree of concentration on electoral politics in order to understand and appreciate the German political system and political process.

The starting-point has to be the electoral system. The behaviour, strategies and decisions of the electorate, of party politicians at federal and Land levels and of the campaign advisers who now possess an increasingly prominent role now in all the principal parties at every election, are shaped and constrained by the electoral system. The existence of a 5 per cent requirement for proportional allocation of seats in the Bundestag and in Land parliaments, and the option of split voting, are just two obvious examples of this fact. Chapter 2 therefore reviews the development of the present-day electoral system, the few serious attempts that have been made to change the fundamental attributes of the system and the importance in recent Bundestag elections of previously neglected details (concerning surplus seats, for instance). The chapters 3–5 examine the ways in which parties on the one hand, and the electorate on the other, react to the electoral process, as ‘producers’ and ‘consumers’, as it were. Chapter 5 consists of a brief review of each Bundestag election since 1949, looking at particularly interesting and pertinent features of the campaign, the operation of the electoral system and the outcome of the election. Chapter 6 moves from a focus on Bundestag elections to an analysis of ‘second-order’ elections (though that description itself requires discussion): the elections to local councils, to the European Parliament (EP) and to Land legislatures. Attention is focused on the inter-relationships between Bundestag elections and these ‘second-order’ elections, to highlight the important differences in the various electoral systems used (all are varieties of a proportional representation system), and to consider the effects which such elections can have on national politics. The concluding chapter 7 poses the question: does electoral politics matter? It assesses the effectiveness of the German mixed-member electoral system and considers the importance of a system of electoral politics in which only rarely do governments change as an immediate result of Bundestag elections.

The concept of ‘electoral politics’

It will be obvious that this book is about more than superficial aspects of electoral campaigns and election results, important though those are. The term ‘electoral politics’ has been chosen as the title of this book to emphasise the complexity of the inter-play of different aspects of elections and to draw attention to the more extensive ways in which elections affect the political system. Elections, then, in the context of electoral politics, are much more than dramatic interruptions to the normal, day-to-day, business of government. It will be suggested in later chapters that, in some ways, politicians are caught up in a permanent election campaign. What is normally regarded as the ‘election campaign’ – the period when the posters appear on the hoardings, the politicians and their helpers go in search of votes at election rallies or on the streets and the mass media elevate election news to their headlines – is, in fact, the product of months and years of planning and preparation. However, no claim is made that all politics in Germany is ‘electoral politics’. The quasi-diplomacy and multilevel political interactions that mark relations with the institutions of the European Union (EU), the manoeuvrings of administrative politics within the ministries in Berlin and in the Länder capitals, the inter-governmental politics within the federal system, are all obviously important features of German political life, and are not, or are only indirectly, affected by electoral politics. Interest groups are another important, if neglected, set of actors in the political system. The cross-party ‘coastal Mafia’ of Members of the Bundestag (MdBs) from Bremen, Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein and Lower Saxony who secure key positions on the budget and finance committees of the Bundestag and are thus in a position to protect projects such as military installations, beneficial to the economies of their northern region, is one example (Der Spiegel 3 August 1998: 42–3). The trade unions which protect the high subsidies of coal miners in North Rhine-Westphalia or the job security and pay levels of those working in the construction of automobiles, the associations which look after the interests of pharmacists, dentists, estate agents and other professions, agricultural interest groups and the organisations concerned with the interests of those in the public service are other examples of groups which play often a significant role in politics but which are relatively unaffected by the outcomes of electoral politics.

Clearly, the electoral system sets the parameters for electoral politics. Germany has a parliamentary system of government, not a presidential system. So elections to the national legislature influence – and occasionally, indeed, may determine – which party or combination of parties forms the government. The details of the system – in particular, the two-vote ballot paper, permitting split-voting and the 5 per cent requirement for allocations of list seats – affect the party composition of the Bundestag and the alternative coalitions which may be constructed. For example, a different government would have been in office in 1969 had either the radical right-wing National Democratic Party (NPD) gained representation, or the liberal Free Democratic Party (FDP) lost it, yet their vote shares were only 1.5 per cent apart. Split-voting ensured the continued representation in the Bundestag of the FDP in 1969, 1972, 1983, 1987, 1994 and 1998: all elections in which the party’s share of constituency votes fell below 5 per cent, but where list vote-share was above 5 per cent (see chapter 4). With the exception of 1998, the FDP was also able to participate in the coalition government formed after those elections, which it could not have done had only those constituency votes determined the proportional allocation of seats. The anxieties which German and non-German politicians have had about the possible resurgence of right-wing extremism have also focused attention on the 5 per cent requirement in the electoral system. So far, of such extreme right-wing parties, only the NPD has come within 1 per cent of qualifying for Bundestag seats since the 1950s, though in Land and local council elections (as well as in elections to the EP) such parties have been occasionally successful in winning seats.

The political parties

Electoral politics is party politics. So campaigning, electoral behaviour by the individual voters, coalition formation and many other aspects of electoral politics are influenced by the shape and pattern of the party system. Many historians hold the view that the failure of the Weimar Republic was due in great measure to the inability of the party system to integrate voters adequately or to demonstrate sufficient political flexibility to form strong and stable coalition governments. This opinion had important consequences for the establishment of a democratic political system in the western zones of occupation once the Second World War was over.

The post-1945 party system which emerged did so under the strict discipline of the licensing system imposed by the occupying governments in their zones. This meant that parties were, at least formally, democratic in their aims and organisation, and that relatively few parties were granted licences in each zone. Some of the parties which did obtain licences were the re-established organisations of pre-war political parties: the Social Democrats (SPD), the Communist Party (KPD) and the Centre party (Zentrum: Z) were the most important examples. Others, such as the Christian Democrats (CDU and, in Bavaria, the CSU) and the Liberals (the FDP), were newly formed parties intended to replace one or more of the Weimar political parties. For the first Bundestag election a large number of parties competed, and many won seats. However, several factors swiftly reduced the number of successful parties so that in 1961 only three parties remained in the Bundestag, increasing to four in 1983 when the Greens won seats. After reunification five parties had seats from 1990 until the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS) lost its representation as a party group in the 2002 election (though two PDS MdBs were elected in constituencies). These factors included the operation in 1953 and 1956 of a more restrictive 5 per cent requirement to win list seats, the constitutional ban on two parties in 1952 and 1956, the ability of the CDU to absorb smaller conservative parties and the tendency of the electorate to concentrate their votes on the two largest parties.

Attempts from time to time to establish a successful new party to the right of the CDU have all failed. There are parties of the extreme right, but these have only sporadic electoral success in second-order elections. None has managed to win seats in the Bundestag since the 1950s. The idea in the 1970s of using the CSU as a fourth party, garnering extra votes for a Christian Democrat majority, came to nothing, especially since any extension of the CSU’s electoral activities beyond Bavaria would inevitably open the way for the CDU to present candidates in Bavaria, to the chagrin of the CSU. Other right-wing parties which have from time to time sought to benefit from periods of CDU electoral weakness, such as the Bund freier Bürger (Association of Free Citizens) in 1994, the East German Deutsche Sozial-Union (German Social Union) formed in 1990 and the Schill party (2001–2), have all failed to make an electoral breakthrough, apart from a few, transient, successes in Land elections in some cases (Raschke and Tils 2002: 55–7).

Of course, the parties in the Bundestag have undergone changes over the years. They have changed their ideologies, in part because such changes were necessary in order to compete more effectively in elections. The SPD became a more open party when it marked the abandonment of its socialist ideology at the Bad Godesberg Congress in 1959, after which it gained between 2 and 3 per cent of vote-share at every election until 1972, when it became the largest single party for the first time. The Christian Democrats diluted their early statist and welfare-oriented policies, to become more recognisably a conservative party, though one that retained its links to the churches. The FDP underwent a thorough change of direction during its ‘wilderness years’ in opposition to the ‘grand coalition’ (1966–69), but then in the early 1980s veered once more to the right of the political spectrum, especially on economic and financial policies. The Greens became a much more pragmatic party after the shock defeat in 1990, when the western German Greens lost representation in the Bundestag. These changes of course affected how the parties regarded each other as potential coalition partners, as well as how the electorate regarded the parties. For example, changes in the CDU and the Greens have meant that discussion concerning the possibility of those parties someday forming governing coalitions at federal or Land level are no longer too fanciful. The materialist–post-materialist cleavage is less prominent. Generational changes in the two parties mean that the CDU is more open to libertarian ideas embraced by some Greens, while the Greens have for their part lessened their demands for policy solutions based on more state intervention and socialist approaches. Both parties would benefit strategically from such an additional coalition option. However, the gap between the parties is still wide. While co-operation in local government is easier because local politics is more issue-based, the ideological basis of national and Land-level political issues makes such co-operation still a distant prospect (Kleinert 2004: 72–4).

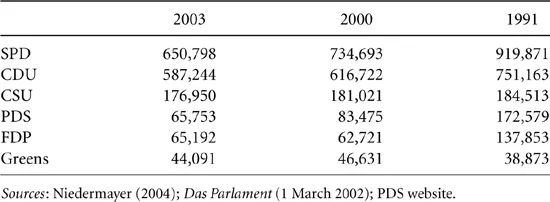

Table 1 Party membership: end-of-year data, 1991–2003

The parties have also undergone changes in their membership. The size of their memberships has fallen in recent years. Though a comparison between 2003 and 1991 is distorted by special factors concerning party membership data in eastern Germany following reunification,1 the general declining trend for all parties except the Greens (which later benefited from the merger with Alliance ’90) can be clearly observed.

These memberships, as in many other countries, were getting older on average. The proportion of members over sixty years of age ranged from 33.4 per cent for the FDP to 45.7 per cent for the CDU (and the PDS in 2002 had 68.7 per cent over sixty years of age).2 Partly in response to the Green party’s insistence on involving females more intensively in politics, the parties have also increased the proportion of their membership which is female. Apart from the PDS, again an outlier with 45.8 per cent female membership (a function to some extent of the age factor), the range of female members is 17.9 per cent for the CSU to 37.1 per cent for the Greens (Niedermayer 2004: 316, 319–20). One way of attracting more female members is to ensure that women become party office-holders and are elected or appointed to public office. The parties have done this by means of formal quotas (the Greens, the SPD and the PDS) and ‘targets’ (the CDU), as well as by other means (McKay 2004a).

The importance of electoral politics in the German political system

How can the importance of electoral politics in the German political system be substantiated empirically? Three indicators suggest themselves: the expenditure of political resources by the parties and politicians; the weight given to electoral aspects of the Basic Law by the Constitutional Court in its decisions; and the attention given to electoral politics by the mass media.

The parties and politicians devote considerable resources to preparation for and the conduct of election campaigns. Significant proportions of the budgets of political parties are devoted to election purposes. In return, large amounts of public funds are paid to parties as subsidies, and the amounts vary according to the electoral success of the parties. Beyond these direct measures of financial resources attributed to electoral politics, indirectly resources required for membership recruitment, local and regional activities and the operation of party central offices are all related to the desire to win votes and to win elections. Of course, it is impossible to draw a line between activities concerned with representation of citizens and of interest groups and those designed to improve the chances of an individual or a party winning an election. Is some activity of an MdB in a constituency aimed at helping with a local problem, or with ensuring favourable publicity and the gratitude of a local organisation which will be of benefit to that politician at the next election? The development of policies or the revision of more general party programmes are undertaken by parties because politicians want to affect policy issues: for example, environmental protection; the possible admission of Turkey to the EU; reform of labour market conditions; changes to the system of health insurance. Nevertheless, it is obvious also that certain policies will be more popular than others, that unpopular policies will lose votes and that in particular the image of a party as defined by its basic programme can have a direct effect on voting support. The Bad Godesberg Programme of the SPD in 1959 or the Freiburg Theses of the FDP in 1971, though in both cases confirming rather than creating the adaptation of party identity for those parties, were influential in bringing to the attention of the electorate the fundamental changes which those parties had undergone. So, whether directly or more indirectly, the financial or other resources which parties and politicians devote to electoral politics is a measure of the significance of elections in the political system.

The Constitutional Court, by the various decisions it has made concerning the constitutional aspects of elections and representation, has emphasised the importance of electoral politics (Kommers 1997: 181–99). It has made judgements about the validity of the 5 per cent clause both as applied in Bundestag elections and for elections to Land legislatures, the freedom of parties to alter party lists after an election (held by the Constitutional Court to offend the principle of ‘direct elections’), the apportionment of constituencies, the constitutionality of proposals for adaptation of the electoral system to be used in the first Bundestag election following German reunification, the existence of surplus seats and the constitutionality of the three-constituency alternative to the 5 per cent qualification for proportional representation. In doing so, it has generated a set of statements which constitute precedent for future cases, relating to issues such as the purposes of the 5 per cent requirement (including the creation of a legislature which can function free from the complication of having too many small parties), the coexistence of constituency and list election within the electoral system and the role of parties in electoral politics. To the cases directly concerned with the electoral system can be added verdicts about the constitutionality of state payments to political parties, the prohibition of parties (and hence of their ability to present candidates at elections), rules about provision of broadcasting and other facilities (such as meeting halls owned by local councils) to political parties in election campaigns with regard to the equal treatment of parties, and the propriety of government departments publishing advertisements emphasising their achievements close to an election campaign (Kommers 1997: 177–81, 201–29). The attention of the Constitutional Court to the finer details of the electoral system and its surrounding procedures (such as postal voting) and their interpretations of the principles of ‘free, equal, secret and direct’ election as stated in the Basic Law emphasise the importance of electoral politics in the democratic system of Germany.

The mass media in Germany devote considerable attention to electoral politics (Eilders, Degenhardt, Herrmann and von der Lippe 2004). The press and broadcasting agencies, in their variety of forms from the populist Bild Zeitung to the Frankfurter Rundschau and the ZDF TV channel, give prominence to stories about election campaigns and election outcomes, but also at other times they report on issues related to elections, such as potential coalition strategies, choice of chancellor-candidates, factionalism within parties and the possible effects on their election chances, the constraints of electoral politics on policymaking likely adversely to affect certain interests. The close relationship between, on the one hand, certain newspapers, magazines such as Focus and Der Spiegel and TV channels such as ZDF and, on the other hand, opinion survey institutes such as Forschungsgruppe Wahlen, is another indication of the extent to which electoral politics has significance.

The dynamic aspect of German electoral politics

T...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- Glossary

- 1 Elections, parties and the political system

- 2 The German electoral system

- 3 Political parties and electoral politics

- 4 The public and electoral politics

- 5 Election campaigns, 1949–2002

- 6 Second-order elections

- 7 Conclusion

- Appendices

- Bibliography

- Index