- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

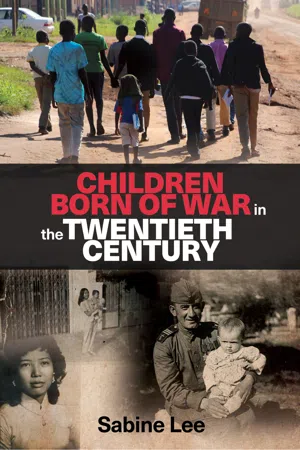

Children born of war in the twentieth century

About this book

This book explores the life courses of children born of war in different twentieth-century conflicts, including the Second World War, the Vietnam War, the Bosnian War, the Rwandan Genocide and the LRA conflict. It investigates both governmental and military policies vis-à-vis children born of war and their mothers, as well as family and local community attitudes, building a complex picture of the multi-layered challenges faced by many children born of war within their post-conflict receptor communities. Based on extensive archival research, the book also uses oral history and participatory research methods which allow the author to add the voices of the children born of war to historical analysis.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Children born of war in the twentieth century by Sabine Lee in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World War I. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Children born of war: an introduction

Few human rights and children’s rights topics have been met with a similarly extensive silence as the fate of children born of war (CBOW) – children fathered by foreign soldiers and born to local mothers during and after armed conflicts.1 Their existence, in their hundreds of thousands, is a widely ignored reality – to the detriment of the individuals and the local societies within which they grow up. Who are they? Where are they? Why are they ignored? And why do they matter? These are some of the fundamental questions serving as a starting point for this study of CBOW in the twentieth century. Beyond the life courses of the children themselves, and beyond giving them a voice to explain their experiences as children of foreign – and often absent – fathers in volatile postconflict situations, focal points of the analysis will be the responses of others to the children whose mere existence frequently creates personal, familial, societal, cultural and political problems in what are often very unsettled postconflict communities and states.

In the early twenty-first century, children fathered by foreign soldiers during and after conflicts are often associated directly with gender-based violence (GBV). This is not surprising. Sexualised violence vis-à-vis women during hostilities is not only the oldest war crime, it is also, albeit in a different manifestation, the youngest such crime.2 Recent conflicts have seen this kind of atrocity used extensively with a level of brutality and disregard for the laws of warfare rarely witnessed in the past. Where there is sexual violence, children are born as a result of it. While the prevalence of conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) has increasingly made the news headlines in recent years, the children conceived as a result of the atrocities have not found their way onto the front pages of the newspapers or the desks of the Whitehall civil servants or non-governmental organisation (NGO) advisors on humanitarian intervention. Since the 1990s – the time of the mass rapes of the Balkan Wars and the numerous African conflicts, epitomised by the Rwandan genocide with its previously unimaginable acts of sexualised violence – rape as a weapon of war has received the attention of academia, the media, governments, NGOs and international courts. International tribunals such as the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR)3 have pronounced judgements in a way that has changed our thinking about rape as a weapon of war, GBV, crimes against humanity, genocidal and sexualised violence. Recently, the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office launched a government initiative aimed at the prevention of sexual violence in conflict,4 and barely two years later, in June 2014, more than 1700 delegates from 123 countries, alongside 73 ministers and representatives of more than one hundred NGOs, met in London for a ‘Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict’.5 A ‘statement of action’ addressing CRSV demonstrated the willingness of many countries world-wide to engage with the issue and to start putting in place action plans for the prevention of GBV in conflicts.6

The increased attention that the subject has received as a political and humanitarian concern has been matched, if not surpassed, by a wide range of academic literature across several disciplines including history, politics, psychology, psychiatry, law and development studies. Yet, in stark contrast to this extensive interest in CRSV, the fate of the thousands of children born as a result of the often coercive relationships between local civilians and foreign soldiers has hardly been noticed. And if children born to victims of CRSV have received little attention, children conceived in non-violent relationships or encounters, many of whom share a variety of the difficulties experienced by children of CRSV victims, have been ignored almost completely. In other words, where there has been interest in CBOW, it has, almost always, been in the context of CRSV. The most prominent example of academic engagement with this subject is Charli Carpenter’s essay collection Born of War,7 which was ground breaking in that it was the first book-length publication dealing exclusively with the children born of wartime sexual violence rather than with their mothers, the direct victims of the assaults. Similarly, Carpenter’s subsequent analysis of children born of the Bosnian Wars, which specifically addresses the issue of human rights agenda setting, does so in the context of GBV in war.8 This focus on children born out of coercive relationships has been evident in what little scholarly and journalistic output has been published since.9 It is not surprising, therefore, that CBOW are often associated directly with sexualised violence. Given the increasingly prominent role of such violence in contemporary armed conflict, it is no less astonishing that CBOW are perceived to be a relatively recent phenomenon. Yet, neither of these conclusions is accurate. Whenever there is armed conflict, soldiers come into contact with local civilians, and in particular with local women; and almost always a proportion of these military–civilian contacts– no matter how strongly the military leadership and the local communities might object – result in intimate relations, whether friendly and consensual or exploitative, coercive and violent. They frequently lead to children being born. This has always been the case and remains true today.

Research data

Even the most existential question of ‘Who are the CBOW?’ cannot be answered easily. No reliable data exists about even their numbers, let alone their life courses. Most recently, and in no way atypical, a major project with the aim of mapping sexual violence in armed conflict globally in the last decade of the twentieth century and sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) by United Nations (UN) peacekeepers since 1999 has been initiated,10 but children born as a result of this violence are not part of this data gathering. The only collection of numbers currently available is based on very vague estimates from a variety of sources, collated for the one existing survey The War Children of the World, a report based on the work of The War and Children Identity Project.11 But the report was issued with a word of caution. When the figures were first published in 2001, it was made clear that while they were the best available, they could not be assumed to be that accurate; the report’s author pointed to the fact that the numbers were at best conservative estimates, and – one might add – at worst guesswork. According to Grieg’s overview, a minimum of 500,000 children were fathered by foreign soldiers in various twentieth-century conflicts; most academics and practitioners working in the field would readily agree that this is an underestimate, caused by lack of any data for a significant number of conflicts, the incompleteness of evidence where it does exist, a general tendency to under-report, and the familiar problem of making accurate assumptions about hidden populations, which applies to large numbers of CBOW.12 A tour d’horizon indicates the scale and breadth of the phenomenon. Thousands of children are believed to have been fathered by French and British soldiers in Germany during the First World War.13 An estimated 10,000–12,000 children fathered by German soldiers were born to Norwegian mothers during the Second World War,14 and the number of German-fathered children of French mothers is estimated to be as high as 120,000–200,000.15 Almost 30,000 children are believed to have been born of unions between Canadian service men and women in Britain and the rest of Europe between 1940 and 1946 (22,000 in Britain, around 6000 in the Netherlands and around 1000 in other European countries).16 Estimates of the number of children born of the post-war occupations of Germany and Austria vary widely and are believed to be at least 200,000 and 20,000 respectively;17 similarly approximations of children born of American GIs and local Vietnamese women during the Vietnam War, generally biracial and many of mixed black/Asian descent, range from 40,00018 to 200,000.19 More recently, conflicts in East Timor, Cambodia and Sri Lanka are believed to have led to the birth of thousands of children conceived of liaisons between military personnel and local women.20 The Balkan Wars of the 1990s, with their Serb ‘rape camps’ and the use of sexual violence as a means of ethnically motivated warfare, demonstrate a new dimension of the phenomenon of CBOW. It is estimated that during the Bosnian War between 20,000 and 50,000 women experienced sexual violence, that about 4000 women became pregnant and that about half of these pregnancies resulted in children being born.21 Several thousand miles further south, around the same time, thousands of children were estimated to have been fathered by Hutu fighters and born to Tutsi mothers in the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide; also in the last decades of the twentieth century, thousands of children were born to Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) fathers and female abductees during the Civil War in Northern Uganda, and fathered by Revolutionary United Front soldiers and born to female child soldiers in Sierra Leone.22

The above illustrates two basic facts relating to CBOW: firstly, it is clearly a global and significant occurrence with a sizeable group of people directly affected; secondly, as the repeated use of the word ‘estimate’ demonstrates, it is a phenomenon that lacks reliable data of even the most basic kind, such as the number of people under discussion. This is as much a consequence of methodological challenges of quantitative research in hidden populations as it is a symptom of a general lack of interest in the fate of CBOW. As one commentator put it:

in the early 1990s organizations such as the international network around children’s human rights concluded that stigma and abuse against children born of war were nonissues from the human rights perspective. Therefore, rather than gathering accurate data, establishing programs to address specific needs, and creating rights-based stories to counter misinformed sensationalism about the topic, organizations promoting children’s human rights chose silence, a silence that is only very tentatively broken today, nearly twenty years later.23

Some notable exceptions to the general disinterest concerning the fate of these children exist. Initiated by Stein Ugelvik Larsen, the above-mentioned War and Children Identity Project was formed, with the explicit goals of promoting and securing the human rights of CBOW.24 While these ambitious objectives have not been achieved, the project has produced an invaluable collection of mostly anecdotal evidence, which has served as a welcome foundation on which to base further research relating to CBOW.

Much of the analysis to follow will be based on estimates, on data which can often not claim accuracy, on material that generally has to be assumed to be an approximation with a significant margin for error or, in some cases, on no available quantitative data at all. This raises some significant methodological issues, as well as questions about the reasons for trying to quantify the problem in the first place. Here it is important to clarify what a quantification does and what it does not aim to achieve. Postulating apparent facts, cloaked in numbers, about GBV or numbers of children conceived of relationships between soldiers and local women, whether or not these were exploitative, is not intended to create a category (or several categories) of victims. Nor does it serve a political purpose in the sense of pointing the finger at certain nationalities or ethnic or religious groups as perpetrators. It does, however, intend to document a complex and multi-faceted history and by implication it intends to create a space for academic and non-academic discourse. If the study draws on numbers, however unreliable these might be, it does so in order to illustrate the magnitude of the phenomenon as well as the fact that it is not limited to particular geographical, geopolitical or historical contexts. In emphasising that it is unlikely that historians will ever know exactly how many women and children have been affected and challenged by the circumstances resulting in the conception of CBOW or in a life as a child born of war, the analysis draws attention to the fact that too strong a focus on the accuracy of the figures is not going to enhance our understanding of the core issues of the experiences of CBOW and their mothers, families and local and national receptor communities. Thus, research is important as a basis of the kind of agenda setting that has been referred to above. It is also important for understanding the nature and magnitude of a problem, for appreciating its complexities and its variations across time and space, and for proposing solutions and – eventually – for monitoring and evaluating progress in developments.

Research on CBOW is still in its early stages, and it is often still seen largely as a side aspect of analyses of CRSV. It is in this area, in particular, that significant developments have taken place with regard to academic research, advocacy and public awareness alike. The most extensive systematic research exists on Norwegian children fathered by German soldiers during the Second World War. Based on historical documents, qualitative interviews, register data25 and quantitative interviews, the life courses of Norwegian CBOW have been analysed thoroughly.26 Beyond this Norwegian case, studies have largely had an explorative character.27 One overview of CBOW as a result of sexual violence in more recent conflicts has been provided in the already mentioned Born of War,28 a volume that offers case studies covering as diverse a range of conflict zones as East Timor, Sierra Leone, Northern Uganda and Bosnia. Over and above visualising the wide geographical extent of the problem, the book also tackles issues rela...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures and tables

- Acknowledgements

- List of abbreviations

- 1 Children born of war: an introduction

- 2 Children born of war: who are they? Experiences of children, mothers, families and post-conflict communities

- 3 Children born of war during and after the Second World War

- 4 Bui Doi: the children of the Vietnam War

- 5 Bosnia: a new dimension of genocidal rape and its children

- 6 African conflicts

- 7 Unintended consequences …

- Epilogue: Children born of war: lessons learnt?

- Bibliography

- Index