![]()

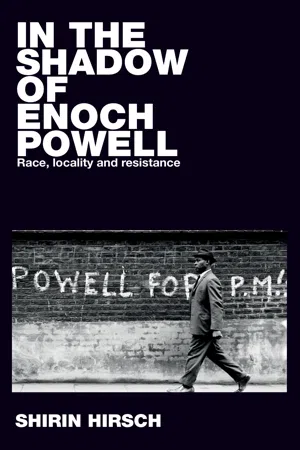

In June 1967 the first live, international satellite television programme, ‘Our World’, was broadcast to the largest television audience ever up to that date, with an estimated 400 million viewers in twenty-four countries. The show closed with a live performance from the Beatles written especially for the broadcast. In the middle of a dreamlike set, the band sang ‘All You Need is Love’ surrounded by balloons, flowers and multilingual placards. At the height of the Vietnam War, the idealistic words appeared to capture the oppositional sentiments of the ‘Summer of Love’. The track went on to top the charts. Nine months after the broadcast, however, Powell’s publicised speech served as a powerful rejection of this counterculture. For Powell, love was certainly not all you needed. Even so, the two moments were not completely separate. In the ‘Our World’ broadcast the Beatles had invited many of their musician friends to sing along with the chorus, including Eric Clapton, members of the Rolling Stones and Marianne Faithfull. In 1976 Clapton went on to declare his support for Enoch Powell as part of an angry tirade at his own concert. ‘Enoch for Prime Minister’, Clapton shouted, and then repeated the slogan the National Front had popularised to ‘Keep Britain White’.1 In under a decade, love had transformed into explicit racism. For the Beatles, Powell’s words also reverberated. In the improvised yet never released track ‘Commonwealth Song’ the Beatles satirised the speech, mocking ‘dirty Enoch Powell’ and his travels around the British Empire; John Lennon, in the voice of a prim old English woman, sings ‘The Commonwealth is much too common for me’. The song went through several versions before ‘Get Back’ was officially released in 1969 as a commentary on counterculture.2

This chapter situates Powell’s ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech within a global period of dramatic changes, a movement described by Sartre as a radical contestation of every established value in society. 1968 was a year marked by the Vietnam War and victory for the Viet Cong. The Black Panthers were powerfully challenging the racism of the American state while in Paris students and workers were in revolt. Peaceful and violent decolonisation spread across the globe and in Czechoslovakia the Soviet Union sent in tanks to crush a rebellion. The turmoil of the old order became dramatically apparent as certainties of the past were confronted.3 Powell’s role within this period, and particularly his ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech, was not obviously located within these changes. In 1965, Powell had described himself as ‘not a revolutionary or rebel or anything like that’, but a ‘party man – a professional Tory’. He claimed not to be bothered about crazes – ‘I’ve got nothing against the Beatles’ – or about fashion – ‘I shall continue to wear a waistcoat to the end of my days’. Instead he argued he was a conventional man and would stick to conventional politics.4 The conservatism of Powell would however break free from party discipline when in 1968 he made a speech that went far beyond the restrained language of his party leadership. Powell’s outburst was both informed by and rejected the eruptions of 1968 and this chapter explores the speech within the deeper transformations of this critical year. To understand the purchase of Powell’s words at this specific moment, the chapter now turns to the post-war period and the sense of stability that permeated many aspects of life. Experiences of this period would be significant in framing Powell’s speech when, in the late 1960s, all that was solid melted into air.

Boom, migration and the long calm

In the post-war period capitalism experienced the longest boom in its history. Mirroring this global trend, Britain was marked by political consensus, trade union partnerships and affluence for many.5 The apparent calm of the country was expressed by a number of thinkers from across the political spectrum celebrating a newfound harmony within the capitalist system. In fact, the Labour Party figure Crosland went so far as to argue that ‘by 1951 Britain had, in all essentials, ceased to be a capitalist country’.6 Crosland was certainly not alone in his thinking and such optimism continued throughout the decade. Four years later Crosland wrote that contemporary society would have seemed ‘like a paradise’ to many early socialist pioneers. Poverty and insecurity were in the process of disappearing as Britain stood ‘on the threshold of mass abundance’.7 Abundance, however, was predicated on a historical relationship which ensured the dependency of the colonial periphery on the centre. This prolonged entanglement was often written out of the national story of Britain, and yet it was a global system that deeply shaped Enoch Powell.

Since childhood, Powell had been wedded to an idea of the nation framed through imperial power. Englishness for Powell was a set of values and a state of mind, and transmitting these great ideals abroad had been his romantic vision of Empire. Such a position was aligned with Conservative ideology in this period, and Powell was, in his own words, ‘born a Tory’. From a middle-class family Powell followed all the traits of a typical Conservative path. Grammar school led to a place at Cambridge to study classics, and then a stint as a professor in Australia. He had grown up with a strong loyalty to imperial Britain, but it was his experience of the Second World War that developed this passion for Empire as he cut his career in academia short and enlisted into the army. Rising up the ranks of the military and removed from combat, his time in India allowed Powell’s love of Empire to truly blossom, seeing first-hand what he romantically described as the ‘spell of England’ projected onto the islands ‘under influence’.8 Empire, for Powell, was a world system deeply enshrined in his very being, interwoven into what it meant to be an Englishman. When the war ended, Powell harboured dreams of returning to colonial India in the role of viceroy. One way to protect the Empire, Powell calculated, was a career in politics. His love of Empire and capitalism were not unique for a Conservative parliamentary candidate, and neither was his election in 1950, as MP for Wolverhampton South West, particularly surprising. Powell’s early life seemed to represent a success story of middle-class aspiration and English conservatism.

Powell’s election as MP was framed by the post-war boom. It was also a time when industry was met with serious labour shortages in Britain. The king’s speech on the opening of parliament in 1951, the first written by a Tory government since the war had ended, declared ‘My government views with concern the serious shortage of labour, particularly of skilled labour, which has handicapped production in a number of industries’.9 Responding to this gap, the government at first focused on the recruitment of white migrants, in an attempt to preserve an imagined white Britain. Nevertheless, migrant numbers from Europe were not sufficient to satisfy the labour-hungry demands of British industry. For a short time it looked as though the British economy would be throttled by a shortage of labour. What saved it was, in Foot’s words, the historical accident of imperialism.10 Drawing from the resources of the Commonwealth, immigrants from the Caribbean and the Indian subcontinent would have to be recruited to Britain.

There had been black communities of sorts in Britain since the 1500s and immigration to Britain in the post-war period was by no means a new phenomenon.11 Over the 1950s there was something of a migrant labour boom, but this did not solely include those classified as ‘coloured immigrants’. The numbers of migrants arriving in Britain from Poland, for example, was actually equivalent to their Caribbean counterparts in 1960.12 Of course, it was the migration of people from the Caribbean and India that received the most attention in this period. Their skin marked them out as internal Others within the nation; they were in Britain but not of Britain.13 These racial hierarchies were framed by a history of British colonialism, where the imagined role of white Britain was presented as that of protecting and overseeing the people, infrastructure and land of darkened colonies. The arrival to British shores of those from the colonies, now legally as equals, was therefore a direct challenge to a racial ideology entrenched within British colonialism.

Simultaneously, however, the rules of Empire also pushed against immigration restrictions within the Commonwealth. Empire had created subjects of the crown and to conceptually reject this also meant threatening the very workings of the system. Speaking some years later, Sir David Hunt, Winston Churchill’s Private Secretary, paraphrased the dilemma thus: ‘The minute we said we’ve got to keep these black chaps out, the whole Commonwealth lark would have blown up.’14 Moreover, recent popular memories of the British war effort were centred on defeating the Nazis and their ideology of racial purity. In this sense a new political campaign against ‘coloured’ immigration was hard to sell to the British public in the years following the war.

At first the numbers of new black immigrants arriving in Britain was relatively small: no more than 2,000 in any one year between 1948 (when the Empire Windrush brought the first arrivals) and 1953. After this date there was a qualitative change and black immigration could be measured in tens of thousands per year. This change was in part because some employers made special efforts to recruit in the Caribbean and India, with travel fares loaned which would be paid back gradually out of salaries earned in Britain. Recruiting industries included the National Health Service, of particular interest to readers here as it was then under the direction of Enoch Powell as minister of health.15 Indeed, for Powell during this period his close attachment to Empire was still tied up with a commitment to a notion of British subjects. In other words, those living within the Commonwealth had a right to migrate to Britain.

All of these workers who arrived from the Commonwealth into Britain were not only permitted to migrate but were significantly encouraged to do so. The 1948 Nationality Act had granted citizenship to residents of Britain’s colonies and former colonies and their passports gave them the right to come to Britain and stay for the rest of their lives.16 Those from the colonies had been brought up with ideas of a superior, wealthy motherland and British life was often imagined with great optimism by future migrants in the Commonwealth. Unfortunately, these hopes did not always materialise and, on arrival, newcomers experienced racism, housing difficulties and underemployment.17 Meanwhile there was a muted acceptance by national politicians of immigrants and their presence was acknowledged as a fact of life. While there were political voices who campaigned against ‘coloured migrants’, it was nevertheless a minority pursuit in the 1950s and early 1960s. Powell was certainly not part of any anti-immigrant campaign in this period. As late as 1964, Powell was arguing that the only long-term route to happiness in his constituency involved a gradual integration process of immigrant communities. Powell wrote that: ‘I have set and I always will set my face like flint against making any difference between one citizen and another on grounds of his origin.’18 This position was no different to the vast majority of politicians in this period, as Powell stressed, arguing that the overwhelming majority of Conservatives would agree with him that integration of immigrants into British life was the most desirable option. The framing of immigrants as an undesirable burden on the nation, something that must be halted, was not part of Powell’s language at this stage. This could be explained by the simple reason that British capitalism had become increasingly reliant on black migrant labour. Up to and including the 1959 election, which the Conservatives won, immigration was nowhere to be seen as a mainstream political issue. The economic boom had protected black newcomer migrants from national attention and instead such migrants often kept their heads down, working hard to build a new life for themselves in Britain. As Stuart Hall put it, they were ‘tiptoeing through the tulips’.19

Race and the end of consensus

Beneath the surface of this long calm, molecular shifts pointed to future instabilities. In the early 1960s the boom of the British economy began to very gradually come to an end. Immigrant workers were still needed, but with not quite the same urgency and scale that had determined the labour market of the 1950s. The position of racialised migrant workers became increasingly fragile within this new context. 1962 was a major turning point in the state implementation of immigration controls. Restrictions were introduced by the Conservative government on the admission of Commonwealth settlers, permitting only those with government-issued employment vouchers to settle. The leader of the Labour opposition in parliament, Hugh Gaitskell, strongly rejected the Commonwealth Immigrants Act, describing it as ‘cruel and brutal anti-colour legislation’. Blackness became equated, officially, with second-class citizenship and with the status of undesirable immigrant.20 The discriminatory legislation, whose obvious intention was to reduce the total annual inflow of black people in Britain, sowed the seeds for future restrictions.

Two years after the Act the Conservative candidate Peter Griffiths unexpectedly won the seat of Smethwick, in the West Midlands, in the 1964 general election, fought on an openly racist platform. ‘If you want a nigger for a neighbour vote Labour’ read the slogan on leaflets in support of Griffiths. This local Conservative victory stood at odds with a national swing to Labour. The Smethwick result therefore seemed to demonstrate that race and immigration were potential issues that could win votes.21 Powell observed the result in his backyard with cautious interest but remained notably quiet on the issue. Lessons from Smethwick were nevertheless drawn across the political spectrum. While Labour had strongly opposed the 1962 Act, in government its position changed. In 1965 it issued a White Paper on Immigration from the Commonwealth, which argued that the essence of the ‘problem’ was numbers. Immigration controls were further tightened, with a particular focus on restrictions on the entry of black people. In March 1968 Labour initiated the passing of a new Commonwealth Immigration Act, introduced with the sole purpose of restricting the entry of Kenyan Asians holding British passports. A special clause in the act gave ex-colonials with white skin the continued right of free entry. This was a transformation within the Labour Party that was honestly acknowledged by Crossman. He wrote that ‘a few years ago everyone would have regarded the denial of entry to British nationals with British passports as the most appalling violation of our deepest principles’. Crossman went on to justify this position, explaining that he supported the bill ‘mainly because I am an MP for a constituency in the Midlands, where racialism is a powerful force’.22 But in so doing, the government also increased the social and political conseque...