![]()

1

Early modern English drama and visual culture

This book discusses early modern English drama as a part of visual culture. But what is visual culture, and why use this phrase in place of the ‘fine arts’ or the ‘visual arts’? In part, this choice is motivated by my concern with exploring the plays in their historical contexts. Shakespeare and his contemporaries would not have recognised the phrase ‘fine arts’. Nor would they have recognised the categories that we might now refer to as the ‘decorative arts’ and ‘crafts’, these terms being products of the eighteenth century.1 It is partly because the phrase ‘fine arts’ is anachronistic for the early modern period that I avoid its use throughout this book, although I frequently discuss visual representations which are identified with this aesthetic category, such as paintings and sculpture. Instead, in this study I approach drama as a part of visual culture, and, within this broad approach, I refer to visual representations and occasionally to the visual arts. These phrases are all as anachronistic as is ‘fine arts’ for a discussion of early modern culture, and so my terminology requires further qualification. To this end, this chapter explores what is meant by early modern English visual culture, and expounds my approach to drama as a part of that visual culture.

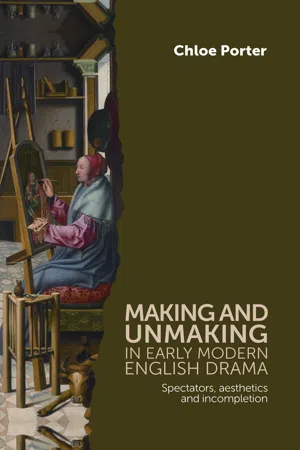

The phrase ‘visual culture’ emerged in art-historical criticism in the late twentieth century, and is usually used with reference to modern and postmodern visuality, although it is notable that the first allusion to ‘visual culture’ is in Michael Baxandall’s pioneering 1972 study, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy.2 ‘Visual culture’ is a pertinent phrase for use in this study because it implies a breadth of visual reference that includes the diverse range of types of work with which an early modern artisan might be involved. Painters in this period regularly carried out decorative work, and, as Lucy Gent points out, paintings in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries were to some extent ‘thought of as forms of surface and wall-cladding’.3 For example, active in the early seventeenth century, Rowland Buckett was a painter whose ‘forte lay in decorative painting’ but was also expert in ‘gilding, joinery, and carving’.4 Examples of his work survive, such as his decorations of a chamber organ made by John Haan and dated to 1611–12, at Hatfield House (figure 1).5

In this swirling composition depicting intertwined bodies of animals, mythical beasts and semi-human figures, Buckett, the son of a German refugee, ‘adapted a plate from Newes Gradesca Büchlein, a suit of grotesques designed by the engraver Lucas Kilian (1579–1637) and published in Augsburg in 1607’.6 This type of grotesque design is also known in the period as ‘antic work’, as in John Florio’s 1598 Italian–English dictionary, where ‘grottesca’ is defined as ‘a kinde of rugged unpolished painters worke, anticke worke’.7

1 Rowland Buckett, detail of painted decoration of John Haan’s chamber organ at Hatfield House (1611–12)

By 1611 Buckett was relatively experienced in organ decoration, as in 1599–1600 he travelled with the organ-maker Thomas Dallam to Constantinople in order to deliver to Sultan Mehmed III the diplomatic gift of an elaborate organ that also functioned as a clock.8 A versatile figure, Buckett was closely connected to the world of early modern drama, working for Edward Alleyn from 1612, and even selling Alleyn ‘painter’s pigments and gold and silver leaf’.9 The painter also collaborated with Thomas Middleton on the production of the Lord Mayor’s Show, The tryumphs of honor and industry (1617), and worked on the set for James Shirley’s masque The Triumphs of Peace, performed at the Middle Temple in 1633.10

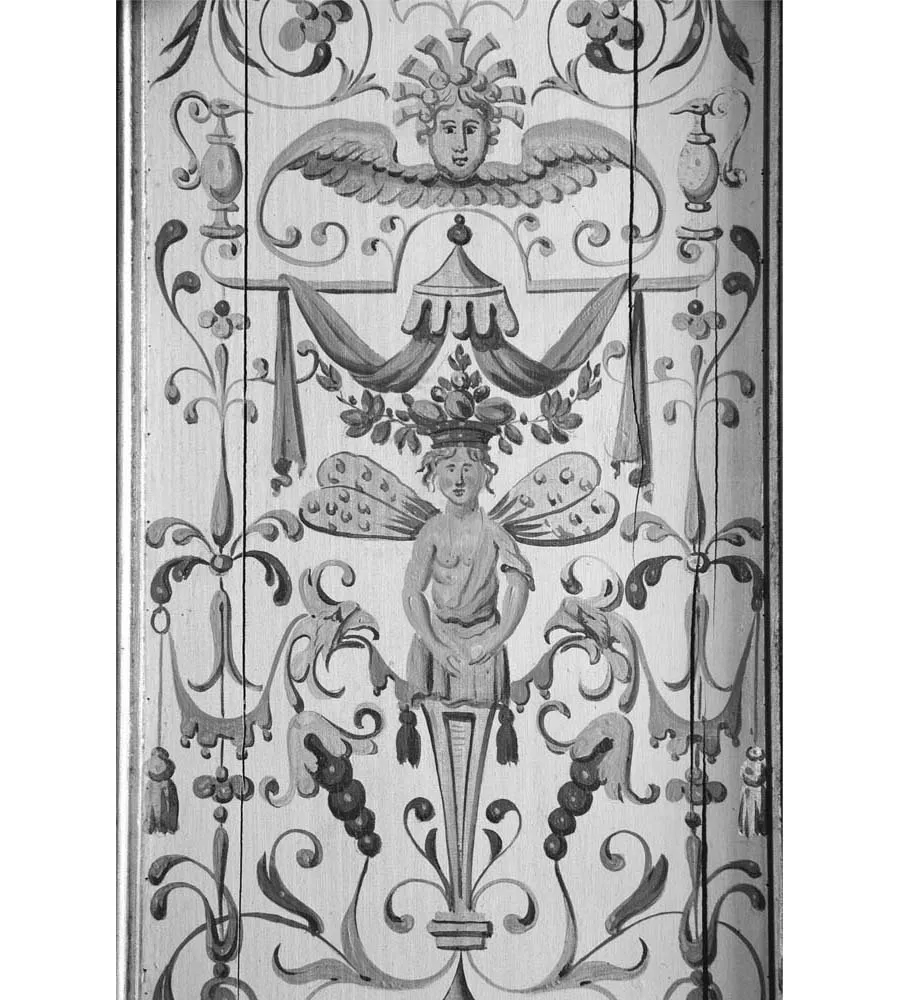

Buckett’s versatility was not unusual in this period. Life as what might be termed a ‘visual artist’ in early modern London seems to have often involved a variety of types of work in collaborative contexts. The painter John De Critz produced portraits of James I and Anne of Denmark in 1605–6, but as Sergeant Painter to the king he also carried out decorative work, such as ‘Cullouring in Gould cullor the Braunches of … Candlesticks in the Cockpitt’, and also scene-painting for masques, such as ‘payntinge … a greate arche with two spandrels, two figures and two pillasters’ in the Banqueting House for the performance of Thomas Campion’s Masque of Squires on 26 December 1613.11 Inigo Jones, the most well-known stage designer to work on the Stuart court masques, was, famously, an architect, appointed Surveyor-General of the King’s Works in 1615.12 In 1630, this role included passing ‘Designes and Draughtes’ for ‘woorkes about the Cockpitt and Playhouse there’ to De Critz, who then directed ‘Carvers and Carpenters’ in implementing the designs.13 That painting was connected to a range of other practices is also suggested by the treatises on drawing and painting which emerge increasingly in the early seventeenth century. For example, Henry Peacham’s The Gentlemans Exercise (1612), which was also published with a different title page as Graphice, discusses ‘drawing’ and ‘the making of all kinds of colours’ for the benefit of ‘all yong gentleman’ as well as ‘Serving for the necessarie use and generall benefite of divers Trades-men and Artificers, as namely Painters, Joyners, Free-masons, Cutters and Carvers’.14 One of Peacham’s later works, The Compleat Gentleman (1622), discusses ‘Drawing and Painting in Oyle’ as one of the many practices appropriate for gentlemen, in addition to ‘Cosmography’ and ‘Musicke’.15 John Bate’s The Mysteryes of Nature, and Art (1634), meanwhile, is divided into four sections; the third covers ‘Drawing, Limning, Colouring, Painting, and Graving’, while the other sections are devoted to waterworks, fireworks and ‘divers experiments’ termed ‘Extravagants’.16 The title page to Bate’s work shows a man painting in the bottom left corner, alongside images of fireworks and contraptions for the production of waterworks (figure 2). In the bottom right corner is a ‘frame’ that functions along loosely perspectival lines and is recommended by Bate for the depiction of ‘a Towne, or Castle’.17

2 John Bate, The Mysteryes of Nature, and Art: Conteined in foure severall Tretises, The first of Water workes the second of Fyer workes, The third of Drawing, Colouring, Painting, and Engraving, The fourth of divers Experiments, as wel Serviceable as delightful: partly Collected, and partly of the Authors Peculiar Practice, and Invention, by J. B (1634), title page

It is against this backdrop of professional versatility that I have chosen to refer to ‘visual culture’ as opposed to ‘the visual arts’ or ‘the fine arts’.

At its broadest, visual culture can mean anything that is seen.18 Visual culture thus also implies the ‘visual field’, but the term ‘culture’ usefully invokes the production of representations as a part of that field. Moreover, ‘culture’ collapses the disciplinary divisions between visual and literary modes of representation in ways that are useful for an interdisciplinary study that looks between modes of expression sometimes understood as distinct. As a constituent of the visual field, it is possible for a play in performance to participate in visual culture in a direct way that does not seem as plausible with reference to the visual arts, although that Shakespeare is ‘himself a visual artist’ is sometimes claimed.19 In addition, the use of the word ‘culture’ directs us away from the idea of image-making and playwriting as the setting up of a representational object, focusing attention instead on representational activity as ‘process’. Raymond Williams states that ‘culture in all its early uses was a noun of process; the tending of something, basically crops or animals’.20 Culture thus implies an action in process, on-going, fermenting, subject to change; a state of affairs that I will argue characterises dramatists’ metatheatrical engagements with the idea of representation. As I explain in the next section, this association between visual experience and matter subject-to-change is also highly pertinent for post-Reformation English visual contexts.

Re-formation visual culture

By the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, English visual culture had experienced tumultuous changes resulting from the religious reforms that began to take effect in the late 1530s. In pre-Reformation devotional practices, the relationship between worshipper and God was extensively mediated through visual representations depicting Christ and the saints. Medieval English churches were ‘filled’ with images of the saints, the embellishment and upkeep of which was paid for by worshippers.21 Decorated shrines held relics of the saints in containers ‘overlaid with decorative plates of gold and silver and the jewels given by generations of pilgrims’.22 Individuals purchased devotional images carved in alabaster depicting scenes from the Passion, or ‘iconographical types such as the Lamentation, Christ as the Man of Sorrows and St. Anne with the Virgin and Child’.23 The centrality of visual representations in Christian devotion in England was overturned by the Protestant Reformation, which insisted that man’s relationship with God be mediated through Scripture and therefore denied the place of images in spiritual communion.24 Christians had long debated the function of images in spiritual life, but the reformist emphasis on the primacy of the word was now directly invested in the identification of religious images as idols; as distracting ‘false’ representations.25 As a result, during the reforms of the early sixteenth century, images were destroyed and removed from churches; wall paintings depicting the saints were whitewashed, the heads and hands of sculptures knocked away or defaced.26 Subsequently, and with the exception of the five-year reign of the Roman Catholic Mary I, bursts of state-authorised and popular iconoclasm targeted images in religious, public and domestic spheres.27

Interlinked with this attack on visual culture was a destabilisation of theories of vision. In the early modern period ‘seeing’ was understood as a material, tactile experience, a view based on medieval and classical models which held that ‘species’ which ‘radiated...