eBook - ePub

The tide of democracy

Shipyard workers and social relations in Britain, 1870–1950

- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This study of British shipbuilding in its heyday brings together original discussions of the organization of production, the relationship between leaders and members of the industry's key trade union, and the involvement of that union in wider labour politics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The tide of democracy by Alastair Reid in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The organisation of craft production

1

Markets and firms

The shipbuilding industry in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Britain presents an interesting paradox. On the one hand, its final products were among the most technically sophisticated of the period. They combined vast metal structures with highly advanced engineering; they included huge cargo ships, powerful naval vessels, and luxurious passenger liners; and their international use was increasingly dependent on the most advanced applied science of the day, including the telegraph and the wireless. Indeed, as a symbol of modernity and national standing shipbuilding had much the same role in this period as aerospace programmes came to have a hundred years later. Yet on the other hand, these superb machines were produced in an environment which was surprisingly crude. It was extremely noisy and dirty, with a great deal of work being carried out in the open and with little provision for refreshment or sanitation; it was very dangerous, as a result of the great heights at which many of the men worked and the chaotic conditions of half-finished ships; and it was difficult to supervise as a result of the widely dispersed indoor and outdoor sites, many of which were hard even to see. Indeed, the key factors of production involved were sheer strength and manual skill, with which management had little contact and over which it had little control.

This was not an image which the firms themselves liked to encourage, and in their official publicity both the texts and the illustrations began with the technical sophistication and huge scale of the products and implied that this was closely paralleled by the conditions of production. In 1909 Fairfields of Govan, for example, proclaimed in a typical style:

Never failing to anticipate the requirements of progressive society, and even directing progress, those to whom the prosperity of the Fairfield Works is due have demonstrated, in a manner that overcomes all theory, the power which well-directed capital can wield as an instrument for general good, as well as the command over the rude forces of nature, which men of prominent ability, industry and wealth can reach.1

This may have assured potential customers of safe and up-to-date products and added to the political confidence of private property in a period of increasing collectivism, but it did not correspond very closely to the day-to-day realities of managing production in British shipyards.

Among those commentators who were prepared to acknowledge the existence of a major paradox in the industry, the usual response was to argue that it would be resolved in the direction of increasingly rational production by the installation of the latest machinery. However, the repetition of this argument at different points over almost a hundred years suggests that it was always intrinsically over-optimistic. In 1884, for example, the Clydeside naval architect David Pollock was so impressed with the development of hydraulic equipment for riveting that he greatly exaggerated its potential impact on hull construction:

Since the early days of iron shipbuilding, when hand labour entered largely into almost all the operations of the shipyard, the field of its application has been gradually narrowed by the employment of machinery. The past few years have been uncommonly fruitful of changes in this direction, and many things point to the likelihood of manual work being still more largely superseded by machine power in the immediate future.2

Twenty years later he acknowledged that the bulk of riveting was still done by hand, yet he hoped that this would soon be changed by the latest pneumatic equipment then being imported from the United States. Though he issued the scornful warning that ‘partially successful methods have been tried from time to time, with, of course, on the part of inventors, a more or less noisy “flourish of trumpets”, signifying no less than the complete solution of the problem’, he himself was still prepared to announce that ‘a complete solution of the shell-riveting problem is not now far distant’.3

This same drive to resolve the paradox of the industry in the direction of more rational shipyard organisation can be found in the sessions of regional technical associations following the high pressure of production for the First World War. The enthusiasm of the younger speakers for scientific management and standardisation was, however, effectively crushed during the discussions of their papers by the sceptical responses of the more experienced managers in the audience. Thus after one particularly sophisticated presentation at a meeting in Newcastle in 1921 on the measurement of output and the monitoring of work in progress, the chairman, having thanked the speaker politely, then remarked that ‘the multiplication of statistics was a fascinating pursuit which became almost a vice, and if it was carried too far one could not see the wood for the trees, and as much time might be spent on producing statistics as on producing ships’, a view which was echoed by many others present.4 The same audience a year later virtually unanimously rejected the proposals of a speaker on standardisation, making it clear that they agreed with the view which he had begun his paper by dismissing, that shipbuilding was ‘“an art, and not a science, encrusted with tradition and hedged about with labour agreements, and to assume that these could be quickly altered or even modified was only to court disaster”’.5

Standardisation was not attempted again in British shipbuilding during the Second World War, but the increasing introduction of welding began to suggest that the rational shipyard might have arrived at last. By 1960, for example, the economist J. R. Parkinson was enthusiastic about moves towards covered working areas, pre-planning, pre-fabrication, and more highly mechanised haulage systems: in effect a vision of flow-line production, if not of automation. However, he was also realistic enough to appreciate that the industry’s heritage posed a major barrier to rationalisation and admitted that:

the foregoing sketch may have given some idea of the vast scope of re-organisation which is needed to bring the majority of shipyards up-to-date from the inter-war period. There are few, if any, shipyards in this country which can claim to have brought themselves fully up-to-date in all respects.6

British shipyards were hampered firstly by the problems of their early start, particularly their cramped locations, and secondly by the deep resistance to standardised production which still characterised both the builders and their customers. In the end Parkinson spent as much time challenging this conservatism and individualism as he did in outlining the revolution he hoped for in production.7

The evidence on shipbuilding therefore needs to be handled with some care for, by being over-impressed with the technical sophistication of the product and relying on some of the more easily accessible statements about the industry, it would be possible to conclude that British shipyards went through a series of stages of increasing mechanisation and rationalisation.8 However, when such statements from the higher levels of the industry or the more ambitious outside consultants are placed in the context of the responses from those with practical experience of day-to-day yard management, it becomes clear that they did not represent either majority practice or even the views of a significant dynamic minority within the industry.9 They were, indeed, little more than wishful thinking and throughout the period of this study shipbuilding in Britain continued to be carried out within the traditional framework of craft production. This fits well with the emphasis by most historians on the slow and uneven nature of Britain’s overall economic development. Even the ‘Industrial Revolution’ of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries is generally seen as having been characterised by relatively small companies, low levels of fixed capital, and practical tinkering rather than major scientific innovations. What makes shipbuilding particularly interesting is that its products were technically so sophisticated yet traditional production methods survived for so long into the twentieth century.

Markets, specialisation and cyclical fluctuations

A large part of the explanation for this paradox of the shipbuilding industry is to be found in the paradox of the market situation which it faced during the period of this study. On the one hand, British shipyards dominated the world market for steam ships and this permitted increasing specialisation and sophistication in their products. However, on the other hand, they were faced with very intense cyclical fluctuations in demand, and this inhibited the adoption of standardised and mechanised production methods.

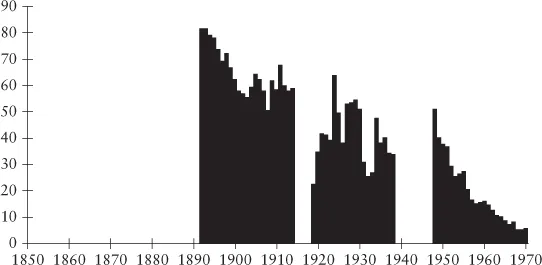

Throughout the whole period from the 1870s to the 1940s the British shipbuilding industry retained a dominant position in the world market, even though its share fell consistently from its peak as the pioneer of the basic technology of steam power and metalworking in the second half of the nineteenth century. From 80 per cent in the early 1890s, Britain’s share of world ship production gradually declined to an average of 60 per cent between 1900 and 1914 (see Figure 1.1). Between the world wars it declined still further to an average of 40 per cent: however, as this was largely due to an expansion in the overseas output of diesel engines and oil tankers, Britain still retained the lion’s share of its traditional coal-oriented markets and its shipyards continued to be forward-looking and innovative.10 Given the opportunity of increased demand during and immediately after the Second World War along with the removal of its German and Japanese rivals, the British industry was thus temporarily able to seize over 50 per cent of the world market again, and it was only with the resumption of normal competition after 1950 that the increasing conservatism of British shipbuilders became evident and led to their rapid and terminal decline.11

This dominant position in the world market between the 1870s and the 1940s was based largely on the high level of demand coming from the British shipping industry, for even after the emergence of overseas manufacturing competitors the bulk of their trade continued to be carried in British vessels. Not only was the British merchant fleet therefore very large but the high reputation of its ships led to overseas demand for second-hand ones, producing a higher level of replacement among British shipping lines. Given the economies of scale permitted by this unusually large home market, British shipbuilding companies were able to establish such a lead that even when other countries became more self-sufficient, usually behind tariff barriers and with government subsidies, they were unable to build up the necessary momentum to challenge Britain’s dominant position. As a result, the combined output of the two most serious competitors in the early twentieth century, Germany and the United States, barely reached 30 per cent of British ship production and there was very little overseas penetration of the British home market until the late 1950s.12

Figure 1.1 UK share of world shipbuilding output (%)

Source: E. H. Lorenz, Economic Decline in Britain: The Shipbuilding Industry, 1890–1970 (Oxford, 1991), Table A.1, pp. 137–9.

This highly favourable market position permitted British shipbuilders to develop a number of effective forms of specialisation. Firstly, and perhaps most importantly, there was a significant degree of specialisation among the suppliers of components to the building yards. Ships’ plates, for example, made up 30 per cent of the national output of the British steel industry before the First World War, thus encouraging a number of firms to focus almost exclusively on this line of work. This was not possible for steel firms in either Germany or the United States, where ships’ plates amounted to at most 5 per cent of national steel output, and consequently tended to be both more expensive and less reliable than their British equivalents. Similarly, the demand for mechanical components, above all marine engines, was high enough in Britain to encourage not only a degree of repetition production but also substantial investment in research and development in a competitive race to lead the field. Again, neither German nor American shipbuilding demand was large enough to permit such developments, and their shipyards remained heavily dependent on British technical innovations and often even on British suppliers.13

The second main form of specialisation in British shipbuilding was that between regions, moving from an early nineteenth-century industry which had been widely dispersed along coasts and rivers wherever there was a local demand for ships, to a late nineteenth-century concentration in a handful of northern districts oriented towards the world market. Indeed there were really two main regions renowned for their shipbuilding firms – the west of Scotland and the north-east coast of England – each with around a third of national output, the rest being largely made up by the output of three smaller centres scattered along the western coastline, at Belfast, Barrow and Birkenhead. This local concentration of companies gave a further edge to the efficiency of British component suppliers, who were able to set up operations in the middle of their markets with lower transport costs and a better knowledge of their customers’ changing needs. Perhaps even more importantly, it produce...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of figures

- Acknowledgements

- List of abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part I The organisation of craft production

- Part II Leadership and democracy in a craft society

- Part III The theory and practice of craft politics

- Bibliography

- Index