![]()

1

On the genealogy of Arthur Cravan

The legend of Arthur Cravan is a projection of the infinite onto the finite. There is a more than pragmatic motive to resist allowing reduction of the myth of Cravan into an abstraction if we are descriptively to recover, reclaim and recondition the poet-boxer from the myth and now the legend that appears so effortlessly to persist. Despite the apparent conformity of the legend to the model (the striding, breathing poet-boxer of 1911–18), it is by Cravan’s condition within the omnipotent realm of simulacra that he now appears almost (but not entirely) exclusively to unfold outside the relation between original and copy.1 Yet we might moderate the reading of simulation as pertaining to nothing more than what we apprehend at the surface; there is, rather, an immanent structure at work in which depth and surface interplay in complex, creative processes of productive combination, as ‘each sense combines information of the depth with information of the surface’.2 The legend is a consequence of our projection of the infinite onto the finite, delivering in the process the ‘double illusion’ that Deleuze has described in a chimera of infinite agony and ecstasy: ‘simulacra produce the mirage of a false infinite in the images which they form’.3 And though we may never be able fully to actualise what is recoverable from the legend, it will remain always and perhaps only thinkable for us, rendering a present memory of Cravan as something that we have made (idea, assemblage, metaphor, plurality, conceptual persona, even legend), a fiction among fictions, achieving the capacity for future joy in all its transformative potential. Where to begin, then, with the ‘false infinite’ of Arthur Cravan? Always, we might suggest, here and now, in whichever ‘present’ we point at, in the centre of a relentlessly ballooning universe.

Evidently, as the art-historical proto-Dada instance, Cravan continues today and exists within broad contexts of deliberation upon proto-avant-garde strategies in the early twentieth century. Cravan gains value in the ongoing revision of such strategic engagement through neo-avant-gardism, post-postmodernity and the incomplete project of capitalist realism. We know in documentary terms, for instance, that Arthur Cravan was briefly active for no more than seven years. He appeared in Paris in 1911, and disappeared in the Gulf of Tehuantepec in 1918. Before 1911, he was someone else – Fabian Avénarius Lloyd, the name that he never fully discarded – delivered of genealogy that ranges the manor lords of Upholland, Lancashire, in the twelfth century, to the King’s Prothonotary within the counties of Chester and Flint in the early nineteenth. His great-grandfather on the Lloyd side was a close acquaintance of the utilitarian philosopher of liberty and advocate of experiments of living John Stuart Mill; and, importantly for that sober nation, among the progeny of this same ancestor was the chair of the Royal Commission into Welsh Sunday Closing.4 What Cravan knew of this genealogy may have been negligible and was certainly selective (what he knew assumed significance for him in mature manifestations and in the fiction that would eventually dominate), and indeed, in all practical terms, effects have no need to resemble their causes. But the method of genealogical analysis put to work so irrefutably by Nietzsche (in Zur Genealogie der Moral (1887) specifically)5 carries the potential at least to show something other than the outward appearances of the effect. Any analysis of origin will demonstrate the blunt absence of essence in all things, or that what we might choose to view as purity in ‘essence’ is more correctly an impurity that admits ‘bastard and mixed blood … [as] the true names of race’.6 As Michel Foucault reasoned, following Nietzsche, genealogical analysis yields identification of ‘the accidents, the minute deviations – or conversely, the complete reversals – the errors, the false appraisals, and the faulty calculations which gave birth to those things that continue to exist and have value for us’.7

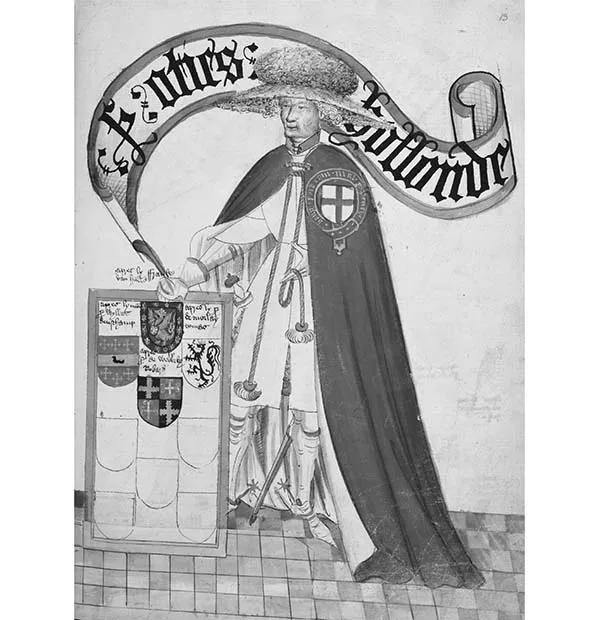

3 Sir Otho Holland (Sir Oties Hollonde), ‘Pictorial Book of Arms of the Order of the Garter’.

The turn to genealogy, then, far from resolving all questions concerning the nature of a thing (as Gilles Deleuze indicated in the first days of postructuralism with his Nietzsche et la philosophie (1962), and as the insistent point in Nietzsche’s critical philosophy), in all practical terms resolves nothing, and is yet a necessary part of the process:

Critical philosophy has two inseparable moments: the referring back of all things and any kind of origin to values, but also the referring back of these values to something which is, as it were, their origin and determines their value.8

There are no judgements to be made; it is rather the potentialities and the possibilities of what emerge through genealogy that gain in the ascendant (the primary genealogical concern for Nietzsche, of course, being moral prejudice (in concepts and in practice) rather than strict ancestry). But the method of analysis prompts equal interest, whether the turn is to the genealogy of morals, or of types of human beings, or of ourselves as ‘men of knowledge’.9 By penetrating the pretentions of universal essentialisms and the vested claims of spirituality, genealogy far exceeds historical documentation and is properly understood to demonstrate the way in which what is delivered is never the inevitable outcome of its genealogical parts, but rather the contingent development of disparate and discontinuous historical forces. What is described in the following passages of the years 1882–87 renders Cravan’s immediate genealogical context in terms of ancestry, but it proposes little that figures in Nietzsche’s properly genealogical account, which signals the philosopher’s break with the accepted practices of historiography in the final decades of the nineteenth century – specifically, Nietzsche’s break with the given practice among ‘moral genealogists’ of confusing origins with purposes.

The parents of Arthur Cravan

The weight and gravitas of Cravan’s paternal lineage are beautifully offset by the obscurity of the maternal line. Cravan’s mother was herself the consequence of the seduction and abandonment of a young instructress in the employ of mid-nineteenth-century English aristocracy, and consequently was raised as daughter to the named Frenchman André L’Arnette and to her mother, identified only as Mme Whitehood.10 Cravan’s mother, then, this daughter of obscure origin, was Hélène Clara St Clair Hutchinson, possessing rare beauty and ‘[d]e grands yeux, un nez d’une pureté extraordinaire, une bouche un peu trop grande formant un visage terriblement spirituel’.11 She was affectionately Nellie, and married Otho Holland Lloyd (Cravan’s natural father) in Lausanne, Switzerland. Lloyd had first become acquainted with Nellie when she was instructress to the children of one of the families in the Swiss town’s large English colony,12 and had paid for her term at finishing school in Lausanne in the summer of 1882.13 The family by whom she was employed allowed her to adopt their name of Hutchinson as goddaughter to the head of the house, and thus Nellie assumed a modicum of respectability for eventual marriage into the family of the Hollands of Clifton and Rhodes,14 upon whom husband and wife would be economically dependent for the immediate future. Following their marriage in July 1884, Lloyd, who had qualified but never practised as a barrister,15 was able to research something of Nellie’s background with the assistance of her mother’s surviving sister, and claimed to have identified a prominent English judge as her natural father.16 For the eighteen months that followed, the marriage proved to be a delicate though generally blissful arrangement between Lausanne and London – ‘I don’t think that, in marrying my father, she felt any love for him; her choice was dictated solely by the question of money’17 – and it was in London, on 6 July 1885, that a first child was born to the Lloyds, named Otho St Clair Lloyd, elder sibling to the future Arthur Cravan.

One month before Otho’s birth, his cousin Cyril was born on 5 June 1885, also in London, a first son from the marriage of Constance Mary Lloyd and Oscar Fingal O’Flahertie Wills Wilde. The latter, yes, Oscar Wilde, was occasionally acquainted with Otho Holland Lloyd, Constance’s brother and senior of three years (both Otho and Oscar had read Classics at Oxford in the mid- to late 1870s; Lloyd went to Oriel College in 1876, Wilde had already gone to Magdalen College in 1874; they reportedly first met each other in Dublin in 1877 or, in Lloyd’s recollection, at Magdalen in 1878).18 Cravan’s later imagined Wildean verdict on his father and Wilde’s brother-in-law Lloyd was not the most complimentary: ‘He is the most insipid [plat] man I have ever met.’19 Wilde had first been introduced to Constance in 1881, and Lloyd warmly greeted his sister’s betrothal, welcoming Wilde ‘as a new brother ... if Constance makes as good a wife as she has been a good sister to me your happiness is certain; she is staunch and true’.20 Constance and Wilde were married in London in May 1884; Constance had lived at the imposing Lloyd family home at 100 Lancaster Gate since 1878, and it was there that she and her new husband briefly stayed before settling as newly-weds into the recently built and (for the Wildes) fashionably renovated number 16 Tite Street, Chelsea.21 Their second son was born on 3 November 1886 and proudly named Vyvyan Oscar Beresford Wilde. Thus, to sum up, Oscar Wilde was uncle to the future Arthur Cravan.

For the Lloyds of Lausanne, in the meantime, the ardour of 1884–85 had been waning somewhat as Otho Holland Lloyd’s attentions became increasingly overtly directed at Mary Edna Winter, Nellie’s friend and the daughter of the principal at her finishing school. And though Nellie’s pregnancy into 1887 delivered the Lloyds a second son, the birth came at a time of upheaval in domestic commitment; in the period that followed, Lloyd left his wife and two children in Lausanne, heading south to Florence in Italy ‘pour une escapade romantique’22 with Mary – an act that would have inevitable repercussions and ultimately irrecoverable consequences. Constance wrote to her brother Otho:

[W]hat a burden you have thrown on poor little Nellie. She writes so very sweetly and kindly but she is such a child quite unfit to take charge of two children, two boys, entirely by herself with no father’s care. I ima...