![]()

1

The ‘offensive body’: the politics of consumption in 1848

‘After much diligent investigation, we find no mention made of the Gent in the writings of authors who flourished antecedent to the last ten years … He is evidently the result of a variety of our present condition of society – that constant wearing struggle to appear something more than we in reality are, which now characterizes everybody, both in their public and private phase.’1 With these words Albert Smith introduced his popular volume The Natural History of the Gent, published in 1847, one of a series of ‘Social Zoologies’, which offers a humorous description of a modern type and its homes and haunts. Yet attendant on Smith’s observation of how the gent’s new way of being is affecting the whole of society is his predicted demise. Smith’s volume concludes with the following prophetic lines:

We trust the day will come … when the Gent will be an extinct species … And then this treaties may be regarded as those zoological papers are now which treat of the Dodo: and the hieroglyphics of coaches and horses, pheasants, foxes’ heads, and sporting dogs found on the huge white buttons of his wrapper, will be regarded with as much curiosity, and possibly will give rise to as much discussion and investigation as the ibises and scarabæi in the Egyptian Room of the British Museum.2

The gent as a type according to Smith is at once fixed and fluid, ubiquitous and doomed, a distinct ‘species’, whose traits nevertheless ‘characterize[s] everybody’.3 I argue that alongside figures such as the navvy, the poor Irish immigrant, the prostitute and the seamstress, the gent was at once marginal and central, acting as a lightning rod for a number of tensions that characterize the mid nineteenth century. Smith’s writings precisely define the gent as a type and locate him within the entertainment venues and shopping streets of late-1840s London. This functioned to distance the gent’s threatening vulgarity from middle-class respectability. In this sense Smith’s volume should be viewed alongside etiquette books that aimed to help the newly moneyed avoid social embarrassment as they rose socially. Although seemingly a figure of fun, because taste and class were elided in his ‘offensive body’, the gent was central to thinking about consumerism at this moment. The gent became a cipher for what was wrong with a society based on mass production, sweated labour, frivolous and vain spending, and uneducated buying choices. Surprisingly, consumption could even be linked to revolution through the gent’s performance of class.

Smith’s fullest explorations of the gent, The Natural History of the Gent published in 1847 and the essay ‘The Casino’ published in 1848, coincided with both Chartism and revolution in Europe. Beginning with a close, reconstructive reading of ‘The Casino’ this chapter works outwards to reveal the larger themes and more serious issues that lay behind the intense interest in the gent at this moment. Too prevalent to be wished into extinction as Smith had hoped, the gent’s untutored form of consumption ultimately motivated the design reform programme of Cole and his circle at the Great Exhibition and the Museum of Ornamental Art, which display prejudicial attitudes to novel mass-produced items of the kind linked with the gent, as will be explored in the concluding chapter of this book.

West Strand: locating the gent in 1848

Early in 1848 Smith identified Laurent’s Casino, adjacent to the Lowther Arcade just to the east of Trafalgar Square, as a special haunt of the gents. This public dancehall was a space of urban leisure with a specific history and associations, where social aspirations could temporarily be put into play through consumer goods and cheap entertainments. The discourse about this location in the late 1840s, which had previously been used for didactic exhibitions of practical science, prefigured questions of the relationship of the serious and the popular, vulgar and respectable, that swirled around the Great Exhibition. Smith’s taxonomy of the gent in the late 1840s was an extension of a project begun much earlier in the decade in the pages of Punch. Although aiming to amuse, the motivation to define social types has parallels in social investigation, such as Henry Mayhew’s contemporary project to document the working class in London. Such projects aimed at control and regulation, as well as description and categorization, but often how these texts aim to do their work reveals as much about the preoccupations of the describer as the subject described. This is no less true in the case of Smith’s work on the gent as urban type.

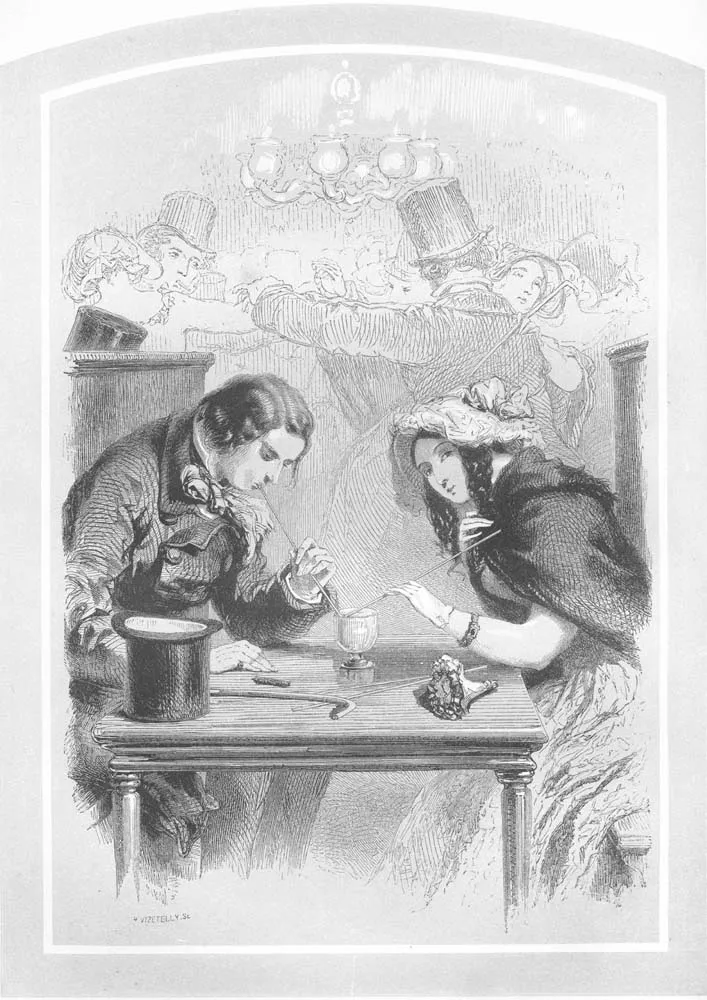

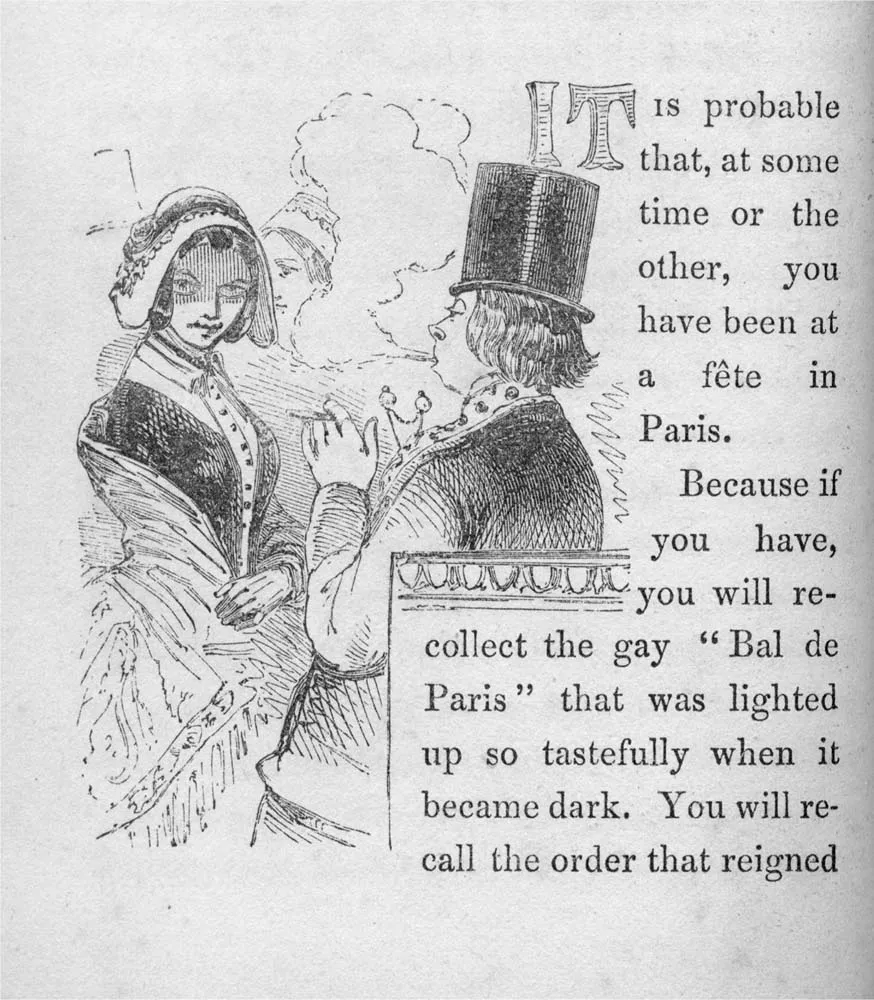

Smith’s essay, ‘The Casino’, appeared in the first instalment of Gavarni in London: Sketches of Life and Character with Illustrative Essays by Popular Writers, also edited by Smith, which appeared in late March 1848.4 Full-page chiaroscuro wood engraving by Henry Vizetelly accompanied the piece, from a drawing on the wood by the celebrated French lithographer and watercolourist, Paul Gavarni.5 The engraving depicts the gent and his female companion at Laurent’s Casino and was one of the twenty-three that eventually comprised the contents of the completed series (see Figure 1.1).6 Gavarni was perfectly placed to undertake this work, having produced illustrations for a series that earlier in the decade had defined Parisian types: the Physiologies. Gavarni may have known Smith’s ‘Social Zoologies’, or Smith or his publisher may have showed them to the artist, as some of the engravings for Gavarni in London seem derived from those publications. For example, Gavarni’s image of two young women with a foot-servant, which illustrates the essay ‘A Sketch from the West-End’, is probably copied from the vignette which appears on page twelve of The Natural History of ‘Stuck-Up’ People. Likewise the image of ‘The Casino’ seems to be a combination of illustrations from The Natural History of the Gent that illustrated the chapter ‘Of the Gent at the Casinos’, notably the initial vignette for this chapter on page sixty-four (see Figure 1.2).7

Gavarni’s image of Laurent’s Casino depicts two figures, one male and one female, seated on opposite sides of a table in a booth. Behind the couple, beneath one of four ‘monster chandeliers’ that lit the venue, we can make out at least five couples dancing, and a man’s top-hat is visible over the partition to the left.8 From the text we also know that the couple is drinking a ‘sherry-cobbler’ through straws.9 Contemporary advertising reveals a popular connection between the sherry-cobbler and Laurent’s Casino.10 Made with sherry, ice, sugar and fruit, it was, Smith writes, ‘not strong to be sure; but this is an advantage, in addition to that of the corresponding modesty of price’.11 The drinking straws form a bridge between the two figures meeting at the rim of their shared glass, suggesting flirtation or courtship. This linkage is echoed by the two additional straws that lie on the table in front of the couple, and pass from the male figure’s cane to the female figure’s posy and bare arm. Other items on the table are the man’s up-turned top-hat and cigar, which together with the woman’s bouquet and prominently displayed bracelet mark out their gendered territory on either side of the table. The phallic cane and the folds between the flowers read as sexually suggestive. The man’s slightly long, curled hair, his ring and short cane, the large buttons to his double-breasted sac coat, and his cigar are all the accessories of the gent, and would have been instantly recognizable. Smith’s essay records that gents were the ‘overwhelming class’ present at the casino.12

The Adelaide Gallery, the hall that housed Laurent’s Casino, occupied a specific yet shifting site within the array of entertainments to be had for a shilling in London. The venue had opened in 1832 as part of a new development on the site of a former slum at the end of the Strand closest to Trafalgar Square. Overseen by John Nash and completed in 1830, the building development was and is known as West Strand.13 On a triangular plot stood a neo-classical, stucco-fronted building supported internally by iron columns. The facade still stands today. The development was bordered by the Strand, William IV Street and Adelaide Street, the latter running behind the church of St Martin-in-the-Fields, which stood on the newly cleared Trafalgar Square. Bisecting the West Strand block was the Lowther Arcade, an indoor shopping street modelled on the Royal Opera and Burlington Arcades that had opened around a decade earlier and were located further west near the fashionable retail districts of Regent Street and Bond Street.14 To the west of the new development were the National Gallery (opened in 1838), the club-land of Pall Mall, Whitehall and St James’s Park beyond. To the east were the less salubrious Hungerford and Covent Garden markets and the slum of St Giles. In many ways the development of the West Strand was an attempt to expand bourgeois and upper-class West End commercial traffic further east, or at least to provide a barrier between the west and east.15

1.1 Henry Vizetelly after Guillaume Sulpice Chevalier (called Paul Gavarni), full-page illustration to ‘The Casino’ by Albert Smith, chiaroscuro wood engraving from Albert Smith (ed.), Gavarni in London: Sketches of Life and Character with Illustrative Essays by Popular Writers (London: D. Bogue, 1849), opposite p. 13.

1.2 Unknown wood engraver after a drawing by Archibald Henning, title letters to chapter 10, ‘Of the Gent at the Casinos’, wood engraving from Albert Smith, The Natural History of the Gent (London: D. Bogue, 1847), p. 64.

1.3 J. Rogers after Nathaniel Whittock, ‘Lowther Arcade’ (detail), engraving from Tallis’s Street Views and Pictorial Directory of England, Scotland and Ireland with a Faithful History and Description of every object of Interest by William Gaspey ([London]: J. & F. Tallis, [1847]), plate following p. 44.

By 1848, it was the gent and more broadly the lower middle class that was the urban type most associated with the West Strand. Besides the entertainments of Laurent’s Casino at the Adelaide Gallery, the development offered forms of consumption that mirrored aristocratic styles, just as its architecture recalled the look of high culture through the vocabulary of neo-classical forms (see Figure 1.3). By mid century, the Lowther Arcade had became famous for its toy and trinket shops, including Dowie’s Emporium of Novelty, Sampson’s Toy Warehouse and the Civet Cat Bazaar, in addition to milliners, confectioners and a seller of sheet music. The woman in Gavarni’s image wears a bracelet and the man a ring. Both could have been purchased at the Lowther Arcade. Indeed, Smith observed in his The Natural History of the Gent that the gent’s flashy and outrageous stock pins in the form, for example, of a girl on a swing, were only sold there (see Figure 1.4).16 An advertisement for Richard’s Repository, at No. 1 Lowther Arcade, gives a flavour of the kind of jewellery up for sale: ‘All is not Gol...