eBook - ePub

Psychological socialism

The Labour Party and qualities of mind and character, 1931 to the present

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Psychological socialism

The Labour Party and qualities of mind and character, 1931 to the present

About this book

This book explores the neglected theme of individual character in British social democratic thought and Labour Party history from the 1930s to New Labour. How important was it for the centre-left that citizens should be 'good people'?

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Psychological socialism by Jeremy Nuttall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Theatre History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

The main purpose of the book

This book focuses on the Labour Party’s attitude to the idea of ‘mental progress’. This idea is perhaps most closely associated with Victorian Liberals and socialists. Stefan Collini suggests:

Progress was the pattern into which the educated late-Victorian Englishman naturally fitted both his perceptions of the past and his expectations of the future. Unless challenged, this was usually implicit … Economic and technological growth was certainly the most tangible manifestation of Progress, and the one which in the later part of the century could be most easily demonstrated. But this was not the most important aspect: it was the, frequently related, assumptions of intellectual and moral advance which provided the fundamental motif of the pattern.1

‘Mental progress’ is defined in this book as incorporating both the moral and the intellectual advance mentioned by Collini. It relates to the idea of citizens both behaving more caringly and less selfishly towards others, and thinking more rationally and logically. Aspects of it are encapsulated in the Victorian idea of ‘character’. Bellamy notes that

character consisted in the ability to rise above sensual, animal instincts and passions through the force of will. A variety of conventional Victorian middle-class virtues clustered around this key concept, such as sobriety, self-help, frugality, industry, duty, and independence, which taught thrift and effort as the means to worldly success rather than luck and an eye to the main chance. Underwriting this liberal outlook was a fundamental faith in the goodness and rationality of humankind and the belief that individual moral improvement would lead to social progress.2

The idea of ‘mental progress’ could underpin both Liberal and socialist thinking. For example, according to Bellamy, the Liberal thinker T.H. Green hoped that ‘once everyone valued the “higher” goods for themselves, then the market would be transformed from a competition in which each person sought to beggar his or her neighbour into one in which everyone strove to outdo each other in moral virtue’.3 And the socialist Graham Wallas, one of the contributors to Fabian Essays (1889), wrote in his chapter: ‘in the households of the five men out of six in England who live by weekly wage, Socialism would indeed be a new birth of happiness. … Education, refinement, leisure, the very thought of which now maddens them, would be part of their daily life.’4

It is not the purpose of this book to suggest that the achievement of ‘mental progress’ was the main purpose of the Labour Party since 1931. Attention to and support of such a goal was clearly only a strand in Labour’s thinking and usually not the most central. But as the Labour Party has been widely seen, by historians and contemporaries, as the most important vehicle for progress in twentieth-century Britain, it is illuminating to study both the ways in which it did explore means of achieving ‘mental progress’, and also, to the extent that it did not focus on such a goal, why that was so, why other goals were deemed more important. A central focus will be on how Labour’s leading thinkers and actors defined socialism, and what role they saw for ‘mental progress’ within that socialist vision. How far was it deemed essential that to achieve a socialist, and thus, perhaps, more cooperative society, individuals must behave more generously towards each other? How much was a popular recognition of the supposed rational superiority or even scientific inevitability of socialism dependent upon the average citizen becoming more intelligent, and therefore better able to realise this superiority or inevitability? And how important was ‘mental progress’ relative to other branches of the left’s and centre-left’s visions, such as the creation of social structural, material and institutional equalities?

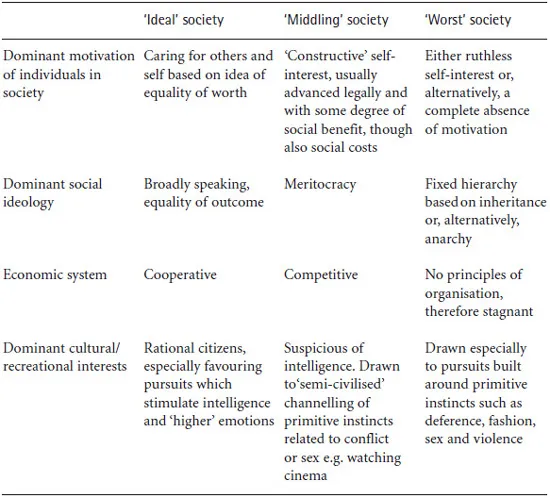

The book is also concerned with how Labour figures’ interpretation of the ‘moral level’ of the citizenry affected their thinking in relation to ‘mental progress’, and indeed to progress as a whole. If most people had not yet reached the ‘higher’ moral and intellectual level, how much of a constraint was this on the achievement of progress, and in what ways could socialist politicians validly operate in the meantime? In such a ‘mental context’, did Labour have a duty not simply to promote ‘ideal’ motives and behaviour, such as altruism, caring, cooperation and rationality, but also to work with, and indeed, seek to spread more ‘middling’-level motives, like competition or ‘common sense’? In other words, if the alternative to ‘middling’ motives was sometimes not ‘ideal’ motives, but ‘worst’ motives, for example, laziness, aggressive militancy or apathy, then did Labour need to take care to ensure its ideal did not become the enemy of society’s mediocre?

Table 1.1 helps illustrate such questions. It is not designed as a rigid definition of what constituted ‘ideal’, ‘middling’, and ‘worst’ societies in the eyes of socialists. Clearly, few, if any socialists saw things in such a systematic way, and many would have placed some features in different columns. Clearly, also, not all the categories are mutually exclusive, and they are often multi-dimensional. The ideal behaviour in cultural terms, for example, has, at different times, been defined on the basis of such diverse features as being active yet reflective, or highly emotionally stimulated and yet tranquil. There were also plenty of twentieth-century progressives who regarded sex as one of the highest, or at least most fulfilling emotions. Instead, then, the table serves as a framework, illustrating some specific features of some socialists’ thought, but also the very broad idea of different ‘levels’ of social advancement. These differing levels help explain why different ideologies at times slid into each other in the twentieth century, in the sense that Labour’s ‘realism’ in accepting a need sometimes to promote ‘middling’, and not just ‘ideal’-level qualities of mind and values was in a sense an acceptance of some validity in the gradualist approach to politics more commonly associated with Conservatism.

Table 1.1 ‘Ideal’, ‘middling’ and ‘worst’ features of society

Finally, the book is also interested in the motivations of Labour thinkers and actors themselves, or, more precisely, in how much they deemed those motivations to matter to the achievement of progress. If ‘mental progress’ was an important component in socialism, was setting a personal example of good behaviour as morally necessary and/or potent a means of achieving socialism as specific policies or even ideas? And if ‘mental progress’ was important, did this mean that a ‘good example’ included one’s behaviour in personal relationships as much as decisions to resist the temptations of private medical care or private schools for one’s offspring? How far could ambitions of elevated personal political or social status be justified if one professed adherence to socialist principles of equality of status and worth?

Having stated the purpose of the book, the remainder of this introductory chapter addresses four main aspects. First, it discusses the existing focus of the historiography of the Labour Party, and asserts the absence of a systematic consideration of its attitude to the issue of qualities of mind and character. Second, it highlights some reasons for this absence. Third, it suggests, in five separate sections, how the theme of this book will illuminate five central issues and debates relating to Labour’s history. Fourth, it outlines the particular approach of the book, and considers methodological questions.

Inattention to qualities of mind in Labour Party historiography

Victorian and early-twentieth-century attitudes towards altruism and ‘character’ have been given some attention, notably by Stefan Collini in his Public Moralists (1991), though Jose Harris could still reflect in 1993 that whilst ‘the role of moral character in late Victorian and Edwardian social thought has been almost universally noted by interpreters of the period, … [it] has rarely received the kind of scrutiny that its historical importance seems to require’.5 But such attention as has been given has not been extended beyond the first quarter of the twentieth century, that is to say into the period when Labour, not the Liberals, were the dominant political party. Throughout the Labour Party’s history, its members and leaders have pursued various aims, their progress towards which has been correspondingly chronicled by historians, including to: build and develop the party as an institution;6 win elections;7 secure internal victories for particular factions;8 differently run, or better manage the economy;9 create egalitarian social structures and institutions;10 fulfil personal ambitions (numerous biographies have charted the course of these ambitions);11 implement policy;12 or think and write about socialist ideology.13 Much enlightenment has resulted from these historiographical focuses, but attention to the role of qualities of mind and character in Labour Party history is not amongst them. The party’s historians have not examined the multi-faceted issue of ‘mental progress’ in relation to Labour’s history to the degree that they have considered, say, economic progress or progress towards equality.

This is not to say that the issue of qualities of mind and character has been entirely ignored in Labour Party historiography. In fact, there have been a number of works, especially in recent years, which have considered themes relevant to that of this book, and from which it benefits. Specifically, the book draws on four existing strands of writing, even though their principal concerns lie elsewhere than a systematic consideration of Labour in relation to qualities of mind and character since 1931. The first strand consists of the loosely connected writing on ethical socialism, ‘moral politics’ and emotions in relation to the party. Peter Catterall has written on the relationship between the Labour Party and Protestant Nonconformists in the inter-war years.14 David Marquand has highlighted the difference between those politicians with a ‘moral’ vision for the citizenry and those without as a cleavage in twentieth-century British political history meriting consideration alongside the more remarked upon division between left and right.15 Borrowing the terminology of Peter Clarke, Marquand suggested that ‘moral’ reformers sought ‘inner changes of value and belief’, whereas ‘mechanical’ ones settled for mere ‘outward changes of structure and law’.16 Which label Marquand applied to which reformers will be discussed later in this chapter. Martin Francis has emphasised that the Attlee governments had a strong ethical vision, as well as one concerned with combating material inequalities through the welfare state.17 Finally, Francis has also explored Labour’s commitment to restraint, rationality and order in the immediate post-war period and its corresponding suspicion of uncontrolled emotion.18

The second strand of writing can be characterised, again loosely, as that relating to the political culture of the party, and to the attitudes of the citizenry towards socialism, or of the Labour Party towards the citizenry. Chris Waters has considered socialist attitudes to popular culture between 1884 and 1914.19 Stuart Macintyre has written about Labour’s and Marxists’ response to working-class political apathy in the 1920s, and reflected on Labour’s sense then that ‘the raising up of public mentality was the regulator of its political progress’.20 Steven Fielding has explored the political mood of the electorate at the 1945 election, suggesting it was not as idealistic as had traditionally been supposed, and, building on this, in collaboration with Peter Thompson and Nick Tiratsoo, he has examined popular political attitudes during the Attlee governments, highlighting both the ethical, moral side of Labour’s vision, even of apparent apparatchiks such as Herbert Morrison, and also the constraint which a relatively non-idealistic citizenry imposed upon the achievement of this vision.21 Lawrence Black has highlighted Labour’s hostility towards what it saw as the immorality of the affluent society between 1951 and 1964, and the electoral damage the party did to itself by the undiscriminating nature of this hostility.22

Third, there has been analysis of the main political parties’ attitudes to specific issues relating to individual morality. Stephen Jones has narrated Labour’s attitudes to alcohol consumption in the inter-war years.23 Peter Thompson has explored aspects of Labour’s perspectives towards the alleged creation of the ‘permissive society’ in the 1960s.24 Turning to the role of specific moral issues in the broader context of British politics, Martin Durham has examined the ways in which the Conservative Party under Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s was unhappy with this ‘permissive society’, and attempted to toughen the rules in such areas as pornography and abortion, though not by as much as many campaigners would have wished.25 Nevertheless, Conservative Party historiography, much less voluminous than writing on Labour, even after the surge of work in recent years, has also given little systematic attention to the issue of qualities of mind and character.

The fourth strand emanates from writers of political science and philosophy. These have begun to highlight the importance of personal attitude and choice to the achievement of progress or socialism, on the basis of the assumption that society is, to some to degree, an accumulation of the personal decisions of the individuals whom it comprises. G.A. Cohen, in his If You’re an Egalitarian, How Come You’re So Rich?, has explored the complex arguments surrounding the neglected question of whether those who profess egalitarianism should give away various percentages of their own income in order to promote it through their personal example.26 Central to Cohen’s thinking on this is his sense that political philosophy has neglected the issue of attitude:

Egalitarian justice is not only, as Rawlsian liberalism teaches, a matter of the rules that define the structure of society, but also a matter of personal attitude and choice; personal attitude and choice are, moreover, the stuff of which social structure itself is made. These truths have not informed political philosophy as much as they should inform it …27

Similarly, Adam Swift has examined the moral issues relevant to the question of how left-leaning parents should make the decision as to whether to send their children to non-compr...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Series editors’ foreword

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 1931–51

- 3 1951–64

- 4 1964–79

- 5 1979–94

- 6 1994–the present

- 7 Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index