![]()

1

Chineseness: theoretical, historical, political Chineseness as a theoretical, historical, and political problem in global art and exhibition

The California-born Chinese American artist Patty Chang is well known for her bodily-oriented artworks, exemplified by performances on video such as In Love (2001), Eels (2001), and Melons at a Loss (1998). Since the late 2000s, Chang has continued her bodily-oriented exploration through video, adopting the transparent, self-reflexive form for expressing the act of crossing borders transnationally as an aesthetic experience. She has traveled to the outer regions and metropolitan areas of China in order to create a series of complex performative and peripatetic engagements, including works such as Shangri-La (2005) based on her trek to the Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Yunnan province; Minor (2010) exploring the ancient Silk Road area of the Turkic Uyghur region of Xinjiang; Letdown (2017), and Invocation for a Wandering Lake, Part II (2017) representing her travel to Muynak and the Aral Sea in Uzbekistan. The more recent projects were part of the collection comprising the retrospective exhibition at the Queens museum titled Patty Chang: The Wandering Lake, 2009–2017.1 Included in the show was the video project Configurations (2017) (see plates 1 and 2), whereby Chang tracks the South-to-North Water Diversion Project and the development of the three aqueducts redistributing the waters of the Yangtze, Huai, Yellow, and Hai rivers. The water had been transferred through the Danjiankou Reservoir in central China to purportedly 53.1 million people in Beijing and Tianjin since it opened in 2014.2 The extent of Chang’s work located in China is significant, and while Chapter 2 is devoted entirely to her transnational embodied expressions, the introduction of her work here in the beginning of this chapter emphasizes her role as a US citizen in China who is ethnically Chinese. The ability to reconceptualize diversity in Chinese identity is made possible by Chang’s use of her Chinese self as a subject and object of video in her continuing bodily-oriented and performative practice. In this way, the artist often functions as a metaphysical representation of her own video observations.

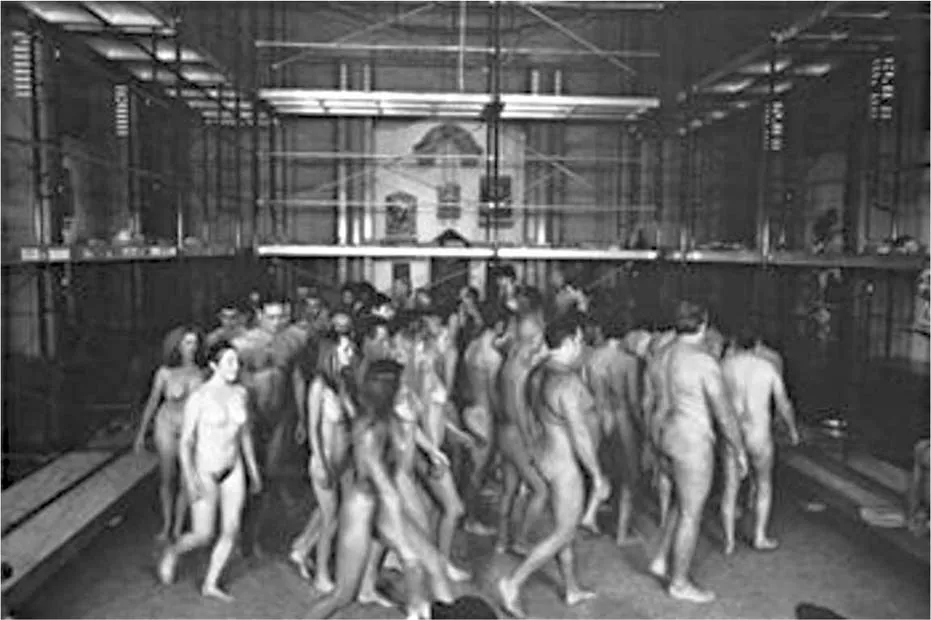

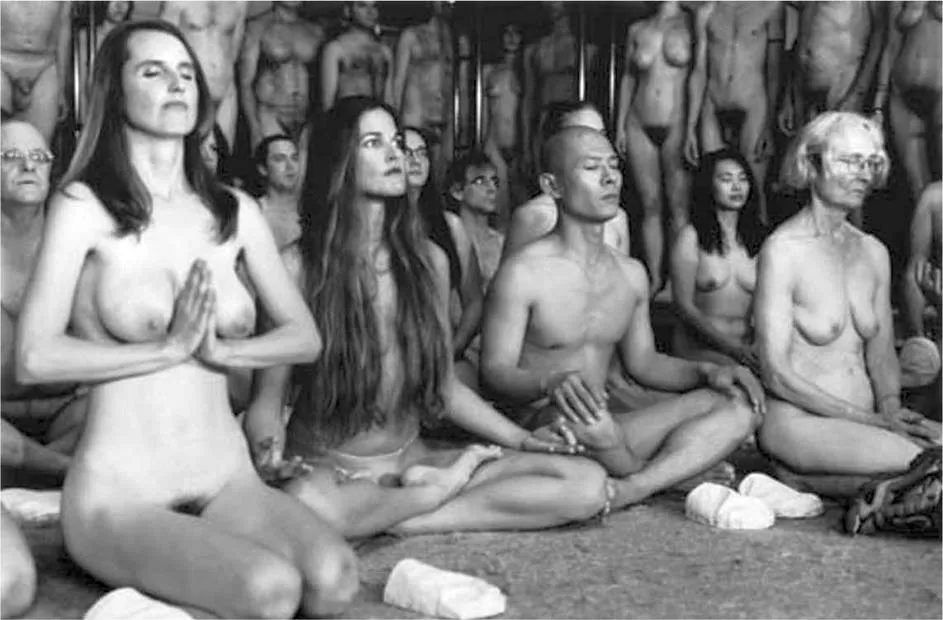

As the counterpart to Chang’s border-crossing, the more conventional concept of transnational movements was expressed by artist Zhang Huan, who presented a series of body-art engagements on the subject of Chinese immigration in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Moving to live in the United States from Henan province, Zhang is a key figure of the post-1980s shiyan meishujia experimental artists and xianchang yishu live-art practices from China. In his 1989 essay, ‘The Peripatetic Artist,’ Jason Kuo had interviewed the artists leaving China for the United States during the country’s conflicted political period because they could ‘express diverse opinions about global exhibitions, about nationalism vs. internationalism and about their relationships to cultures other than their own.’3 But Zhang was well known for staging collaborative performances (with other performers as well as local townspeople) mostly in the environs of Beijing.4 And instead of focusing on difference, as demonstrated in his 1999 performance in Seattle, Hard to Acclimatize (see figures 1.1 and 1.2), Zhang continued to collaborate with artists and members of his new community in the United States while presenting his body art in group and solo shows around the world. Hard to Acclimatize explores the dynamics of how individuals ‘acclimate’ to the actions of the group at large, resulting in a dramatic expression about assimilation. The fifty-six performers, presenting an hour-long performance at the Seattle Asian Art Museum, consisted of academics, gallery owners, and Seattle residents who were invited to the event. Zhang theatricalizes the role of the Pied Piper by leading a group of nude performers through a series of physical movements such as running rapidly around in a circle and exercising methodically using Tai Chi motions. As each performer attempts to ‘follow the leader’ under the simplest rules of the childhood game, the challenge is to stay in step with the rest of the crowd. Viewers are led to feel the awkward effort made by the group as they attempt to synchronize their physical movements.

1.1 Zhang Huan, Hard to Acclimatize, 1999, performance at Seattle Asian Art Museum

1.2 Zhang Huan, Hard to Acclimatize, 1999, performance at Seattle Asian Art Museum

By conceptualizing the complex process of assimilating into a new social environment, Zhang’s bodily-oriented expression creates an entirely different visual-sensory understanding of what constitutes a community. Performance artists adopt the bodily-oriented medium to connect with the audience in a somatic way, and in Zhang’s expression of the immigrant subject, the issues of ethnicity and race become personal in the body to body connection with the audience. In his artist’s statement, Zhang explains the objective of his ‘staged actions’ as aiming to ‘explore migration and relocation, reinscripted meanings, and anxieties about shifting cultural boundaries.’5 The huayi ethnic Chinese who lives outside of China is different from the huaqiao who is staying elsewhere temporarily. Zhang went on to emphasize the personal nature of the performance by adopting the new title, My America, for the series of works initiated by Hard to Acclimatize, including My New York for the 2002 Whitney Biennial. Zhang’s exploration of different forms of ‘acclimatization’ are expressed through foregrounding the actual body in immigration as the subject of art, thereby staging an embodied human representative that supplants the abstracted figure of ‘the immigrant’ in American political discourse. Exacerbated in the age of Trump with his border wall and refusal of asylum seekers, immigration in the United States is generally reduced to the statistics for legislated quotas that signify refugee movements at any given moment in history. The very origin of the restrictive exclusion act in US legislation began in 1875 with Chinese immigration and the Page Law. The historical figure of the ‘cheap laborer’ is usually defined by the racial stereotype as differentiated from the figure of China’s ‘new wealth’ associated with the moneyed-class of visa-holders. Zhang provides an aesthetic experience that upends the political dynamic by making a human connection with the viewer, an exchange that shows the potential of the medium of body art for expressing issues of immigration in the twenty-first century.

As exemplified by Chang and Zhang’s works, the performance of Chineseness is related to issues of nationalism, migration, citizenship, boundaries, and embodiment; through an exploration of these determinants of identity, the engagements of global art today can be connected to the modern history of art and cultural representation. The potential for making these issues apparent is one that bodily-oriented art engenders, and the case studies of artists like Chang and Zhang in this book focus on the artistic medium that can reveal the difference among diverse Chinese identities, usually ascribed to mainland China. As established in the corpus of theory by Amelia Jones, performance and bodily-oriented art have expanded the vocabulary of contemporary art, and their integration with video art provides another key form of engagement through phenomenological encounters of an ontological ‘self’ mediated by film.6 Artists adopted the embodied expression because of the significance of artistic identification by Chinese affiliation, but the emergence of post-1980s Zhongguo xiandai yishujia as the new contemporary art from China has brought to the fore questions regarding what should be considered as ‘Chinese art.’ The change after Deng Xiaoping’s 1980s reforms was a paradigmatic shift in regard to both the Western views toward China’s economic modernity and the emergence of a hybrid form of contemporary Chinese art. Under Deng’s ‘famous four-character policy gaige kaifang, a reform of the economic system and an opening up to the outside world’ brought the import of Euro-American legacies through literature, materials and new exchanges.7

By the 1990s, the first generation of artists who graduated from the reopened universities and art schools that were closed during the Cultural Revolution (1966–76) had established a syncretic Chinese/Western form of contemporary art. Art theorist Zhu Qi explains that the ‘forms of modern art, performance art, installation, video and conceptual photography, which emerged with the New Wave or Avant-garde Movement in 1985, are often referred to as pioneering or experimental art.’8 But Zhu states clearly that in China, none of these ‘pioneering’ movements exist in the ‘narrow sense of the terms as the Western world defines them. In fact, it can only be said that such forms of art in China are elite forms of art that derived their sense of modernism, post-modernism, postcolonialism from the particular experiences engendered with in those rising industrial countries in Asia.’9 The rapid changes for art in China have unfolded over the decades since the 1990s – from a repressive regime for government-controled exhibitions to the state sanctioning of corporate-sponsored museums. By the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century, the ‘elite forms’ of China’s art became a dominant factor in the emergence of the global art category, verifying the growth of contemporary artistic production outside of exclusively European and North American countries. But, as Zhu emphasizes, the pioneering movements in China were perceived as such by the Euro-American art institution. Moreover, Chinese American artists were never considered as part of the movements in China. In the aftermath, the question of artistic authenticity and what constitutes ‘Chinese contemporary art’ compels new approaches to addressing identification and artistic subjects – primarily the difference in identifying artists from Hong Kong, Taiwan, and diasporic Chinese artists from elsewhere – which is the question addressed by this book. In other words, an inquiry into ‘Chineseness’ is a historical and specific one that involves the contested meaning of the term, used both in the Orientalist distinctions of the past and, more recently, as a fluid, unstable, unfixable meaning of ‘Chinese’ in historical and contemporary discourses for the staging of art and culture.

A discursive history of Chineseness

The conceptualization of Chinese identity as related to artistic representation specifically can be clarified by reviewing the history of the word Chineseness in cultural analysis. The 1990s shift in China and in the greater global order provides the key historical periodization for marking the critical theoretical discourse in Chineseness. As defined by Meiling Cheng, Chineseness is an ‘ambiguous, fluid and [a] potentially deterritorialized concept which may be employed by individual subjects – native, diasporic, sinophonic or affiliated by choice – as a multivalent identity marker.’10 Cheng describes a diverging and variable form of identification that is particular to Chinese constituents and communities in the flux of changing political administrations and migrating populations in the twenty-first century. The term has been adopted in today’s vocabulary and used in both scholarly and mainstream descriptions including the Discovery Channel’s 2014 television series, Chineseness: The Rise of Chinese Art.11 The use of the term by the television program was primarily to denote the production of Chinese artists who move across borders between China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

The general acceptance of this terminology in the contemporary zeitgeist has shifted from the earlier context. As late as 2005, many scholars considered Chineseness to be a contentious term and it was rarely used in discussions about art. In the aftermath of Edward Said’s 1978 book, Orientalism, the recognition of the Orientalist imaginary led to the quest for authentic cultures that were not produced by the European imagination. When Rey Chow published her influential 1998 essay ‘On Chineseness as a Theoretical Problem,’ she argued that the very ‘notion of “Chinese” is the result of an overdetermined series of historical factors, the most crucial of which is the lingering, pervasive hegemony of Western culture.’12 Chow refers to the Orientalist debates predicated on the European representation of ‘subject races’ explained by Said as inclusive of ‘Arab, Islamic, Indian, Chinese, or whatever’ in the colonialist ideology reducible to the most simplified logic: ‘There are Westerners, and there are Orientals.’13 Asian Americans, in particular, considered Chineseness to represent the reductivist logic of Orientalism and as an appropriation of Chinese culture by the West...