eBook - ePub

Adapting Frankenstein

The monster's eternal lives in popular culture

- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Adapting Frankenstein

The monster's eternal lives in popular culture

About this book

Mary Shelley's Frankenstein is one of the most popular novels in western literature. It has been adapted and re-assembled in countless forms, from Hammer Horror films to young-adult books and bandes dessinées. Beginning with the idea of the 'Frankenstein Complex', this edited collection provides a series of creative readings that explore the elaborate intertextual networks that make up the novel's remarkable afterlife. It broadens the scope of research on Frankenstein while deepening our understanding of a text that, 200 years after its original publication, continues to intrigue and terrify us in new and unexpected ways.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Adapting Frankenstein by Dennis R. Cutchins,Dennis R. Perry, Dennis R. Cutchins, Dennis R. Perry in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Dramatic adaptations of Frankenstein on stage and radio

1

Frankenstein’s spectacular nineteenth-century stage history and legacy

Lissette Lopez Szwydky

MUCH OF THE SIGNIFICANCE of Mel Brooks’s Young Frankenstein (1974) lies in its engagement with Frankenstein’s adaptation history and early cinema conventions, which it accomplishes through a brilliant mix of parody and homage. The more they are well versed in Frankenstein’s film history, the more viewers are able to appreciate the jokes in Young Frankenstein that cover a full range of characters, scenes, props, and film techniques, alongside literary, film, and cultural critiques.

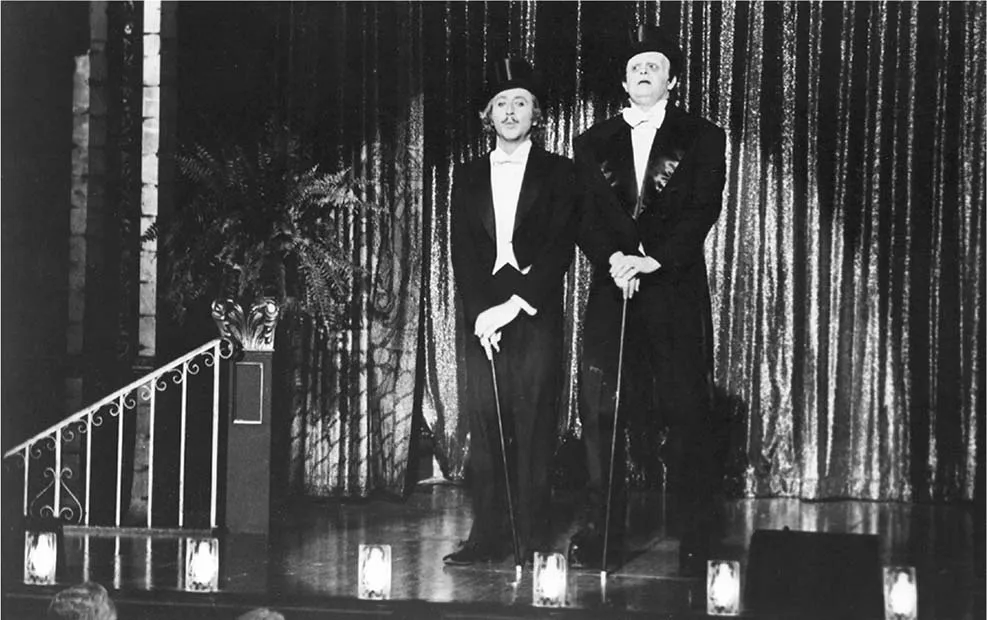

Audiences familiar with Frankenstein’s full adaptation history might find another layer in Young Frankenstein. In one of the film’s most memorable scenes, the Creature dances a duet to Irving Berlin’s ‘Puttin’ on the Ritz’ and performs tricks for treats to a sold-out theatre audience (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Gene Wilder as Frederick Frankenstein and Peter Boyle as the Creature in Young Frankenstein (1974). Directed by Mel Brooks. © 20th Century Fox.

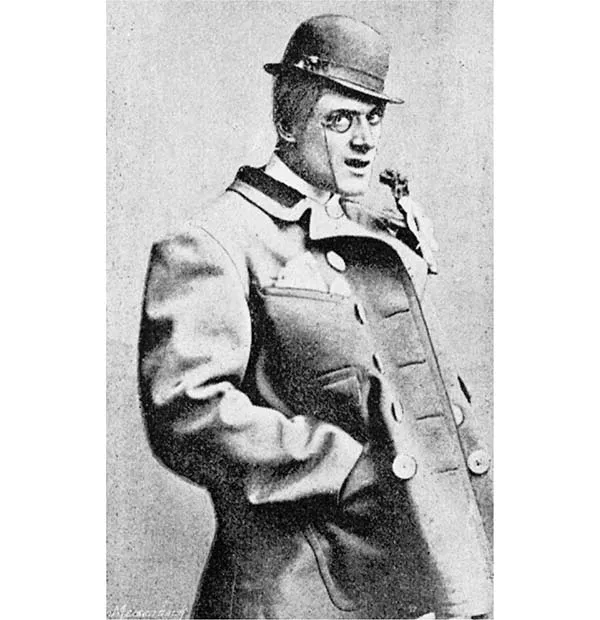

The scene may be original to Frankenstein’s film history, but it directly invokes the novel’s nineteenth-century stage history, which also took many forms – melodramas, farces, and burlesques. Song-and-dance routines such as the one in Young Frankenstein were common in nineteenth-century stage productions, such as Frankenstein; or, The Vampire’s Victim, a musical first staged at London’s Gaiety Theatre in 1887. Like the 1974 parody, the 1887 burlesque took its most immediate inspiration from several earlier Frankenstein adaptations, Gothic thrillers, and other popular entertainments. One might say that Frankenstein; or, The Vampire’s Victim was the Young Frankenstein of its day. Both adaptations recycle scenes and situations from previous dramatisations, suturing them into new fabrications of the Frankenstein legend. Where Young Frankenstein both lampoons and pays homage to the Frankenstein films of the 1930s and 1940s produced by Universal Studios, Frankenstein; or, The Vampire’s Victim borrows from early melodramas and comedies that began the work of transforming Frankenstein’s monster into a cultural icon, starting in 1823 (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Promotional image of Fred Leslie as the Creature in Frankenstein; or, The Vampire’s Victim (1887). First performed at the Gaiety Theatre. Photo credit: Mander and Mitchenson / University of Bristol / ArenaPAL.

Although much of Frankenstein’s film history is well known to scholars and fans alike, the nineteenth-century dramatisations are less known outside of specialised circles. The most influential study to date is Steven Forry’s ground-breaking book, Hideous Progenies: Dramatizations of Frankenstein from Mary Shelley to the Present (1990), which includes a comprehensive list of plays appearing between 1823 and 1986 and production details and commentary for many of those plays. Audrey A. Fisch’s Frankenstein: Icon of Modern Culture (2009) builds on Forry’s formative work, providing extensive summary and analysis of the nineteenth-century plays, as well as Victorian political cartoons (also discussed by Forry), and twentieth-century adaptations on stage and screen. Two twentieth-century plays are given extended discussion: Peggy Webling’s Frankenstein (1927), the most direct predecessor to James Whale’s iconic treatment of the monster; and The Last Laugh (1915, co-written by Paul Dickey and Charles Goddard), the first original Frankenstein drama of the twentieth century, which also happened to take cues from a comic 1849 predecessor, Frankenstein; or The Model Man (Fisch 156). Fisch brackets her study of Frankenstein’s adaptation history with discussions of the novel’s literary history, early reception, and later critical history. Ultimately, Fisch demonstrates how feminist scholars in the 1970s and 1980s paved the way for the literary canonisation of Shelley’s novel, while adaptations transformed Frankenstein; or The Modern Prometheus from novel idea to cultural icon.1

Like all narratives that are repeatedly repurposed, Frankenstein adaptations must be considered within their respective historical, political, and cultural contexts, as Susan Tyler Hitchcock does in Frankenstein: A Cultural History (2007). While Forry and Fisch delve into the specific details of the early plays, including their reception and production details, Hitchcock’s socio-historical approach narrates the evolution of the Frankenstein Complex across multiple media from the nineteenth century to the present, showing how these adaptations provide unique takes on the relevance of the Frankenstein Complex.2

Frankenstein is certainly one of the most adapted novels, but it is not alone. Adaptations were a common sight on London’s nineteenth-century stages. Diane Long Hoeveler’s ‘Victorian Gothic Drama’ shows the overwhelming proliferation of adaptations, including stage versions of John Polidori’s The Vampyre (1819), Victor Hugo’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1831), and Alexandre Dumas’s The Corsican Brothers (1844), to name a few. Victorians saw at least eight adaptations of Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre in the fifty years following the novel’s publication.3 Charles Dickens’s works were staples of the Victorian stage, often while the novels were still in serialisation.4 Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde was transformed for the stage only months after its publication in 1886.5 Gothic narratives in particular found themselves at the centre of the century’s fascination with adaptation. Hoeveler’s Gothic Riffs: Secularizing the Uncanny in the European Imaginary, 1780–1820 (2010) tracks popular Gothic narratives and themes through the multiple media and genres available to nineteenth-century consumers, including opera, drama, melodrama, ballads, and chapbooks.6 Of all of these, nineteenth-century popular theatre provides the most obvious legacy to contemporary afterlives of nineteenth-century novels like Frankenstein. As Hoeveler explains, ‘There is no question that contemporary viewers of the horror film … owe a visual and cultural debt to the many advances and experiments made by the Victorian Gothic drama’ (69). The proliferation of adaptation in the age of film and digital media is an extension of the nineteenth-century’s fascination with emerging technologies and commercial popular culture.

Much of the existing Frankenstein-focused scholarship has worked to recover, catalogue, and contextualise Frankenstein’s early stage history, bringing to light for modern audiences pieces that have long been forgotten, despite their importance in shaping the Frankenstein story over nearly two centuries. The trend in scholarship is, unsurprisingly, to focus on individual adaptations and highlight their respective distinctions. My work builds on the earlier scholarship by taking a different approach – foregrounding trends (as opposed to individual plays) established by the early dramatisations that have become central to the iconography of Frankenstein. In this chapter, I track several major scenes and trends that have come to dominate the Frankenstein Complex today – creation scenes, death scenes, and rehabilitation plots – and trace their developments to the nineteenth-century stage. By better understanding the origins of iconic moments and trends in Frankenstein’s adaptation history, we not only better understand the connections between past and present but also gain a stronger awareness of adaptation’s role in Frankenstein’s narrative evolution from novel to what Paul Davis calls a ‘culture text’. Unlike most existing scholarship, I treat melodramas and comedies based on Frankenstein with equal interest because the latter genre is typically ignored but has equal cultural force as the more ‘serious’ adaptations of the nineteenth-century stage and later films.

Presumption sets the stage

Returning to England from Italy in the summer of 1823, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley wrote to Leigh Hunt (her late husband’s long-time friend and publisher), ‘Behold! I found myself famous!’ (378). The reason? A melodrama based on Frankenstein was a hit at the English Opera House and a second printing of the novel now featured her name (the novel was originally published anonymously). The 1823 printing (arranged by her father, William Godwin) owed its appearance to the drama’s popularity. Shelley attended the play on 29 August and was impressed, as she tells Hunt:

The play bill amused me extremely, for in the list of dramatis personæ came, ——— by Mr. T. Cooke: this nameless mode of naming the un[n]ameable is rather good. … The story is not well managed – but Cooke played ——’s part extremely well – his seeking as it were for support – his trying to grasp at the sounds he heard – all indeed he does was well imagined & executed. I was much amused, & it appeared to excite a breath[less] eagerness in the audience. (378)

Shelley enjoyed the excitement Cooke’s performance produced for the audience, but was less pleased with the plot changes. As in the novel, the Creature in Peake’s drama is nameless. His creator’s name is Frankenstein. They don’t get along. These were some of the only similarities between Shelley’s Frankenstein and the version staged nightly in London.

Richard Brinsley Peake’s Presumption; or, The Fate of Frankenstein premiered on 28 July 1823 at the English Opera House and forever changed the fate of Frankenstein in popular culture. The play notably introduced several alterations that would set new standards for subsequent adaptations. For example, the hunchbacked assistant Fritz (often Ygor/Igor in later film adaptations) was introduced in a comic role written expressly for Robert Keeley, the theatre’s resident comedian. The character was a hit with audiences and would be reconfigured in most nineteenth-century dramatisations as well as in twentieth-century adaptations such as James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931).7 Sometimes this ‘assistant’ is more of an intellectual equal who collaborates on experiments, such as the diabolical, and humorous, Dr Pretorius in Bride of Frankenstein (1935) or the ethically conscious, and more serious, Dr Krempe in The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), as well as several other assistants in the Hammer Films. In Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994), Victor is joined by both Henry Clerval and Professor Waldman in his initial experiments (although they remain unaware of the human project that builds on their earlier findings). All examples differ widely from Shelley’s novel, where Victor Frankenstein’s isolation not only enables his experiments but also shapes his mental and emotional instability.

Since the introduction of the lab assistant character in 1823, one is hard pressed to find an adaptation where Frankenstein works alone. On the nineteenth-century stage, Fritz served as an interlocutor between Frankenstein and theatre audiences by narrating the creation scene in the first two stage adaptations. He became a ‘fall guy’ of sorts in James Whale’s 1931 film by bringing the well-meaning scientist an ‘abnormal’ brain and then serving as a convenient and justifiable first victim, due to his cruel treatment of the monster. In Bride of Frankenstein (1935), Fritz is temporarily replaced by the forgettable Karl (played by Dwight Frye, who also played Fritz in the previous film), before Bela Lugosi introduced ‘Igor’ to the Frankenstein lexicon in Son of Frankenstein (1939). Karl makes a comeback in The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958), becoming a willing (although tragic) participant in the scientist’s monstrous experiments. ‘Eye-Gor’ is one of the most memorable characters of Young Frankenstein (1974), where he serves as Frederick’s guide in navigating the Frankenstein castle, its secrets, and the family history, while also guiding audience interpretation through his exaggerated inferences and inflections. Some more recent reimaginings expand the role significantly. The animated film Igor (2008) makes the hunchback assistant’s role central to the mad scientist trope. Victor Frankenstein (2015), the most recent big-budget release, starring James McAvoy and Daniel Radcliffe, tells the story that everyone ‘already knows’ from Igor’s perspective. All of these lab assistants find their ancestor in Peake’s 1823 play.

Peake’s Presumption had other permanent influences on the Frankenstein Complex. For example, although many of the 1820s melodramas included avalanches or nautical imagery from the novel’s frame narrative, Peake eliminated the frame narrative featuring Robert Walton’s Arctic expedition. Later adaptations followed suit and Walton was omitted in most adaptations for the next two centuries.8 Instead of the cross-continental travel that we get in the novel, the action in Peake’s play is confined to a single geographical setting and all scenes take place very close to the Frankenstein home. Forry and others have chalked up this change to the necessity of nineteenth-century dramatic conventions that would have required the plot to unfold over a shorter time period with fewer scenic changes. However, films are typically more flexible with regard to scene changes and timelines, suggesting that the continuation of this trend in later adaptations is less easily explained. Why, for example, is Frankenstein’s laboratory located in his own cellar in the first Hammer film, The Curse of Frankenstein (1957)? Budgetary limitations are often used to explain the change; however, much of this film’s plot plays up the proximity of home and family, and although it seems a major departure from the portrayal of the Frankenstein family’s demise in the novel, the relocated lab still enables the domestic destruction seen in this film.

The ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Notes on contributors

- Introduction: The Frankenstein Complex: when the text is more than a text: Dennis R. Cutchins and Dennis R. Perry

- Part I: Dramatic adaptations of Frankenstein on stage and radio

- Part II: Cinematic and television adaptations of Frankenstein

- Part III: Literary adaptations of Frankenstein

- Part IV: Frankenstein in art, illustrations, and comics

- Part V: New media adaptations of Frankenstein

- Frankenstein’s pulse: an afterword: Richard J. Hand

- Index