![]() Part I

Part I

Russia and Central Asia![]()

Russia

1

Russia's response to terrorism in the twenty-first century

Ekaterina Stepanova

Introduction

The definition of terrorism used in this chapter interprets it as premeditated use or threat to use violence against civilian and other non-combatant targets intended to create broader intimidation and destabilization effects in order to achieve political goals by exercising pressure on the state and society.1 This definition of terrorism excludes both the use of force by insurgent–militant actors against military targets and the repressive use of violence by the state itself against its own or foreign civilians. This author's definition predates and is more narrow and concise than the 2011 so-called ‘academic consensus definition’ of terrorism.2 It is also close to the list of criteria that are employed, for the purpose of data collection, by the world's largest database on terrorism – the US-based Global Terrorism Database.3

An emerging degree of consensus in academia on the definition of terrorism does not, however, question – and, further, even underscores – the fact that terrorism displays a wide variety of forms and manifestations and is a highly contextual phenomenon. Terrorism's main hallmark is its unique ability to disproportionately affect politics and its asymmetrical communicative, intimidation and destabilization effect, intended to far exceed the immediate, direct human and physical damage caused by a terrorist attack. This broader destabilizing effect largely depends on how well terrorist activity is tailored to a specific political context. For instance, a single or rare Islamist–jihadist terrorist attack with a limited number of fatalities anywhere in an otherwise peaceful, developed and democratic Europe may produce a much larger political resonance than either hundreds of minor non-lethal terrorist incidents by local separatists, or a series of mass-casualty terrorist bombings in the midst of ongoing hostilities in the world's major conflict spots, such as Iraq, Syria or Afghanistan.

Along with other systemic factors and more concrete specifics of counterterrorism as a security function, it is the highly contextualized nature of terrorism itself that partly explains why the main centre of gravity of anti-terrorism remains at the national (state) level. The national dimension in countering and preventing terrorism remains critical, even as terrorism itself is increasingly transnationalized and international cooperation on countering terrorism has significantly intensified in the early twenty-first century, especially following the attacks of September 11th, 2001, in the United States. All international agreements on anti-terrorism notwithstanding, an individual nation's response to terrorism is highly contextual and is shaped not only by the dominant type and level of terrorist threat (which varies significantly from one state and society to another), but also by the general functionality of the state; type of political and governance system; and degree of social, ethnic and other diversity and integration, etc. This is true for Western and non-Western nations alike, as well as for such a ‘special-case’ country with a hybrid identity as Russia, with strong historical and cultural ties to the West, but firmly and, perhaps, irreversibly outside the West as a political and security space and value system.

In the 2010s, the main context and source of terrorism in post-Soviet Russia – the protracted armed conflict in the North Caucasus – has largely faded away from the world's attention as a hotbed of high-profile terrorism and a major jihadist battleground. This is only partly explained by the shift of global attention to other or new major centres of terrorism activity of the Islamist bent, such as Iraq, Afghanistan, the Maghreb, or West and East Africa, and to growing manifestations of Islamist–jihadist terrorism in Western countries. The main explanation draws upon a set of major changes that occurred domestically in the Russian/North Caucasian context over the decade following the mid-2000s.

First, Russian perceptions of the centrality of terrorism and other violence linked to the North Caucasus and its impact on Russian national politics have changed significantly. Through the mid-2000s, two bitter wars in Chechnya (the first one 1994–96, and the second one lasting from late 1999 to the late 2000s) and terrorism generated by that on-and-off armed conflict had dominated domestic violence and the security agenda in Russia. Violence in and from the North Caucasus had been the first-order issue in national politics. In contrast, from the late 2000s to the early 2010s, the North Caucasus case no longer dominated national politics, as the situation there started to stabilize and the violence started to decline. It was also effectively overshadowed both by other domestic developments (e.g., a wave of mass non-violent civil/pro-democracy protests in 2011–12) and by select crises in the neighbouring states with major domestic implications for Russia (the 2008 conflict in South Ossetia/Georgia, the accession of the Crimea to Russia following an unconstitutional change of government in Ukraine in early 2014, and the separatist armed conflict in Donbass that started in late spring of 2014).

Second, even in terms of domestic sources of violent threats, the North Caucasus no longer poses the single largest, overwhelming problem. Instead, it has become just one of at least three main domestic security issues, along with two other, closely interrelated processes:

- The rise of right-wing extremism and nationalism in the late 2000s, directed especially against migrants, mostly from Central Asia and the Caucasus (with violent manifestations mostly taking forms other than terrorism: i.e. provoking violent scuffles, public beatings, ethno-confessional vandalism, and even pogroms and mass disturbances)

- Mass, uncontrolled and largely illegal labour migration and the growing problems of integration of migrants.

By the early 2010s, a combination of these two issues had arguably become more problematic on a national scale than any terrorism/militancy of North Caucasian origin.

Third, the main form of violent extremism in the North Caucasus – the insurgency that combined guerrilla-style combat with terrorist tactics – has itself undergone some major shifts in the early twenty-first century. The critical ones have been the gradual disintegration of what was a more consolidated ethno-separatist insurgency in Chechnya and a shift to a fragmented, less intensive violence of a more explicit Islamist–jihadist bent that spread across the wider region, while its original hotbed – Chechnya – became relatively pacified.

While the North Caucasus at large remains one of the most problematic regions in the Russian Federation and low-level violence resurfaces in different spots across the region, terrorism of North Caucasian origin ceased to be the most destabilizing domestic security threat in Russia. How did Russia arrive at this stage, following two bitter wars in Chechnya – wars of the type that, in principle, cannot be won – and despite major past failures and deficiencies in confronting terrorism? How did Russia's response to terrorism evolve over time, especially in the twenty-first century? What are the main specifics of Russia's response to the problem that allowed it to significantly diminish the threat in the 2010s, as compared with the previous decade? Why does this response fall short of a long-term solution? What new sources of terrorist threats, beyond the North Caucasus, have emerged for Russia, domestically and transnationally, and how are they managed? And finally, what broader lessons, if any, may be learnt from Russia's response to its main type of terrorist threat? Before addressing these questions, it is useful to have a look at where Russia stands, in terms of the scale, intensity, level and dominant type of terrorism threat, compared with the rest of the world.

Terrorism in Russia in the global context

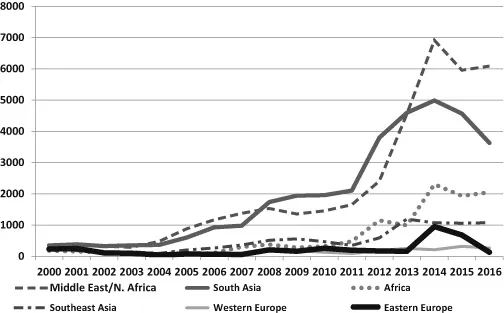

A useful starting point is to acknowledge the fact that, in the first decade and a half of the twenty-first century, global terrorism dynamics were heavily and increasingly dominated by regions other than Eastern Europe or post-Soviet Eurasia. The most explicit global pattern of terrorism during this period involves a combination of two trends. The first trend is a sharp general increase in terrorism (with 2013 and 2014 as peak years not only for the period since 2001, but also for the entire period since 1970 that is covered by the best available terrorism statistics).4 The second trend is a sharp increase in and disproportionately high concentration of terrorist activity in two regions – the Middle East and South Asia (figure 1.1) – with all other regions lagging far behind (including Eastern Europe, where terrorism statistics were heavily dominated by Russia until 2014).5

This sharp increase of terrorism in the Middle East and South Asia in the 2000s was primarily driven by a spike in terrorist activity in Iraq and Afghanistan, and occurred not before but after both countries had become central targets for the US-led ‘war on terrorism’. The military involvement led by the United States was the key factor that set forth the dynamics of escalating armed resistance in these two Muslim countries that was directed against US/Western troops backing weak proxy governments, and gradually morphed into and overlapped wit...