- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Approaching the Bible in medieval England

About this book

Traces how the Bible came to be known by lay people through different mediums. It brings together intellectual and religious history with art history, music, literature and social history to trace how the Bible was sung and preached, revered and studied in thirteenth- and fourteenth-century England.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Approaching the Bible in medieval England by Eyal Poleg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Bible and liturgy: Palm Sunday processions

Introduction

And when they drew nigh to Jerusalem, and were come to Bethphage, unto mount Olivet, then Jesus sent two disciples; Saying to them: Go ye into the village that is over against you, and immediately you shall find an ass tied, and a colt with her: loose them and bring them to me. And if any man shall say anything to you, say ye, that the Lord hath need of them: and forthwith he will let them go. Now all this was done that it might be fulfilled which was spoken by the prophet, saying: Tell ye the daughter of Sion: Behold thy king cometh to thee, meek, and sitting upon an ass, and a colt the foal of her that is used to the yoke. And the disciples going, did as Jesus commanded them. And they brought the ass and the colt, and laid their garments upon them, and made him sit thereon. And a very great multitude spread their garments in the way: and others cut boughs from the trees, and strewed them in the way: And the multitudes that went before and that followed, cried, saying: Hosanna to the son of David: Blessed is he that cometh in the name of the Lord. (Mt 21:1–9)

The Gospel of Matthew was read during the Palm Sunday procession and served as the rationale for the day’s liturgy. A comparison between the biblical narrative (with parallels in Mk 11:1–11; Lk 19:28–38; Jn 12:12–16) and its liturgical re-enactment, however, may result in a few raised eyebrows. If ‘The liturgy was the primary context within which medieval Christians heard, read and understood the Bible’,1 then why are many of the liturgy’s crowning moments nowhere to be found or marginalised in the biblical narrative; where are elements that defined the day in medieval England: the children and the palms, the ornate gates and the familiar hymns? These liturgical traits reveal a gap between the Bible and its re-creation; they appear, time and again, in visual images and literary narratives and attest to the way liturgy has shaped the knowledge of biblical events. This chapter traces the gap between Bible and liturgy through a close analysis of the liturgical event, to reveal how texts, locations, performances and objects brought the Bible to life while simultaneously subjecting it to the demands of faith and exegesis. Beyond the seamless unity of the liturgy, we can appreciate how the Gospel narrative was joined with other biblical episodes, as well as apocryphal or extra-biblical texts presented in biblical guise.

Palm Sunday provides a fertile ground for the study of biblical mediation. Located at the end of Lent and the beginning of Holy Week, it combined joy and sorrow, the unmasking of images and contemplation of the Passion. In the form of a procession, it brought the Bible into a local landscape and made parishioners into active participants in re-creating the Gospel narrative. Palm Sunday was widely depicted on church walls and lavish manuscripts; its texts reverberated in Middle English literature; and its performance was re-created in civic processions. What makes the day even more significant for the study of biblical mediation is the fact that this memorable biblical story does not lend itself easily to liturgical re-enactment. Liturgical processions were made to emulate Christ’s reception at the outskirts of Second-Temple Jerusalem in the towns and villages of medieval Europe. Transforming the biblical event into a liturgical spectacle required a high degree of creativity and led to unexpected logistical problems, such as the need to procure palms in cold climates. The liturgy sustained ancient Hebrew words and Graeco-Roman rituals within the medieval world, long after the reasons for their existence had ceased to exist. Liturgical ingenuity preserved the peripatetic nature of the biblical event as a procession, and came up with solutions to problems of protagonists, location and emotional response, inherent in the Gospel narrative. This chapter follows the course of the Palm Sunday procession in late medieval England. It begins with its spatial dimension, then the liturgical paraphernalia are considered, as are the stations: the chants of the first station; the Gloria laus and its spectacle that follows; a para-liturgical moment in the speech of Caiphas at the third station; and the move into liturgical time in the fourth. The chapter ends with a model for the evolution of Bible and liturgy.

Palm Sunday was celebrated in variety of liturgical elaborations, from those performed in modest parish churches to those in wealthy cathedrals.2 Recreating these requires use of a range of sources. Liturgical manuscripts, such as processionals, customaries, missals and breviaries, contain a wealth of information on the medieval ritual with its texts, tunes, and performance. Nevertheless, these manuscripts have two shortcomings. First, they usually describe the rituals of monasteries and cathedrals; only a handful of surviving manuscripts belonged to parish churches, and even these often portray a liturgy designed for a larger community. Rather than evidence of performance, these liturgical manuscripts witness attempts to impose hegemonic uses on local communities.3 Secondly, the practicalities of the performance, from dress and actors to paraphernalia and locations, are discussed only briefly in rubrics that are few and far between. These manuscripts were commissioned by trained professionals for their peers, and much information regarding the practicalities of recurring rituals was taken for granted.

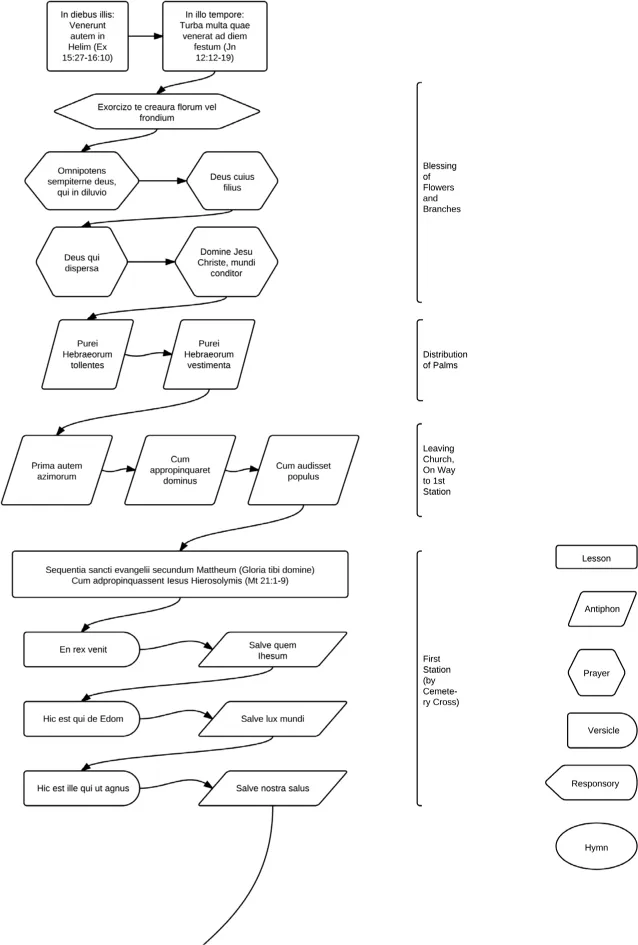

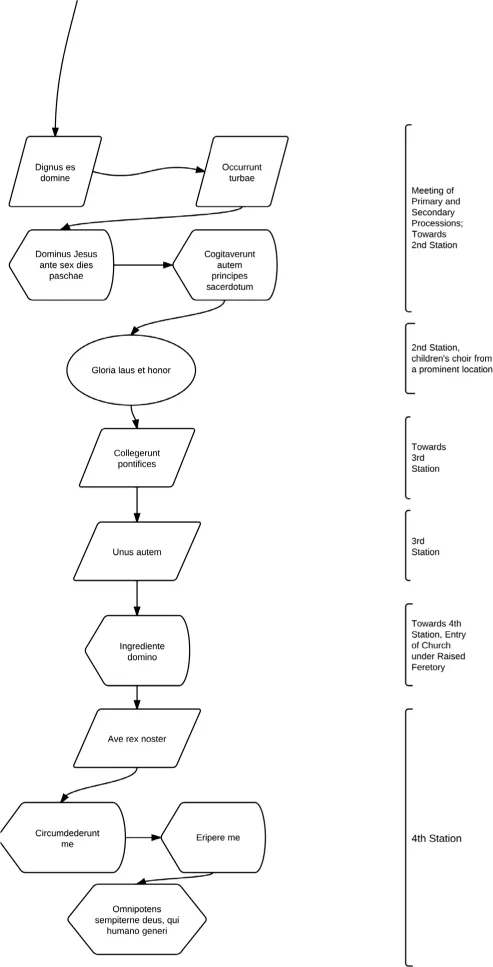

Figure 1 Palm Sunday procession according to the use of Sarum

In order to provide a fuller picture of the day’s liturgy, this analysis draws on a variety of sources both within and without the immediate remit of liturgical manuscripts. In illuminated manuscripts, church murals, literary narrative or chronicles, ample evidence exists for the liturgical celebration, often intertwined with a description of the biblical event itself. Beyond the simplicity of printed editions, the manuscript evidence is complex. It tells of local variations and bears witness to unfamiliar customs and hidden controversies, all of which help to trace the hidden facets of the medieval rite. This survey gives precedence to the use of Sarum, the liturgical rite performed in the Cathedral of Salisbury that became hegemonic in the later Middle Ages, while also addressing local uses and variations from religious houses in Norwich, Lincoln, York, Hereford, and Barking Abbey.4 The overwhelmingly textual nature of the ritual described by the liturgical manuscripts should not divert one’s attention from the performance of these texts. As argued by Tom Elich, the sensory qualities were key to the medieval liturgy.5 In order to encompass the richness of this experience, the actors, gestures, locations and objects – whenever known – are portrayed. Similarly, the musical qualities of the text are examined, to demonstrate how these served to highlight specific components or preserve the integrity of a liturgical scene. The performative strata corroborate written texts to create a complex and challenging picture of the biblical event, which was presented to lay and clerical audiences alike.

Locating Palm Sunday

Attempts to follow the path of Christ and his followers raised an obvious question, where was one to commemorate Palm Sunday? Other biblical stories such as the Last Supper, Crucifixion, and Resurrection took place in identifiable locations: the places which came to be known as Cenaculum, Golgotha, or the Holy Sepulchre. Re-enactment within the confines of a church posed little difficulty. Yet, Palm Sunday took place on the road between the Mount of Olives and Jerusalem. This is not merely an unnamed location, but one outside the city of Jerusalem. The peripatetic nature of the event was modified already in the emerging liturgy of the early Christian Church. In late fourth-century Jerusalem, the Spanish pilgrim Egeria witnessed a liturgy that preserved the transitional essence of the day, and re-created the acts of Christ in the very places where he trod. Even this early liturgy tied the day’s performance to sacred landmarks, which had more to do with the theology of the emergent religion than with the biblical narrative. The crowning moment of the day took place on the slopes of the Mount of Olives, where the biblical narrative was re-created in its original setting with hymns and the carrying of palms. Unlike the biblical story, the day began and ended within the city of Jerusalem, at the churches of the Golgotha and the Holy Sepulchre.6 The joy of welcoming Christ was linked to the memory of his Passion, manifested for all to see in the places of the Crucifixion and Resurrection.

In medieval Europe a less literal route had to be employed in the re-creation of the biblical narrative. A sacred procession came to dominate the commemoration of the day, preserving the biblical narrative and wording (procedere, Jn 12:13), while introducing an array of fixed locations to ground the biblical event in the local landscape and to ease in its dissemination. This was a gradual transition. The Constitutions of Lanfranc (c. 1070), which introduced a new monastic liturgy to Canterbury and St Albans after the Norman Conquest, combined stationary and transitory elements by referring to the activity of ‘statio facere’ (making a station).7 Later uses omit the accompanying verb, as stations became the places where the bulk of the liturgy was performed. Two types of processions emerged in post-Conquest England: one circled a church, and the other had entered through a city’s gate. In Sarum, where the former prevailed, there were four stations: the graveyard cross, a prominent location for Gloria laus, the west door of the church, and in front of the rood. In Hereford and Lincoln, the procession went further afield, and the town’s gate became the place of the second or third station. Some variations were permissible owing to church size or weather, and the York processional offers the option of leaving the city or staying near the church. The two variants shared more than their differences suggest. When the procession exited a city, it was often done nearby its main church, as in York or Lincoln, where the procession remained by the Minster, keeping mostly within the close.8 Both variants preserved the outdoors element, emphasised the idea of entry (either to a city or church) and designated a raised platform for the chant of the Gloria laus.

In the common use of Sarum the first station took place at the cemetery found adjacent to churches or cathedrals. There the congregation assumed the role of the crowd of Jews awaiting the coming of Christ. The link between liturgy and landscape endowed the graveyard cross with a new meaning. The 1229 constitutions of William de Blois, Bishop of Worcester, refer to Palm Sunday procession in their discussion of cemeteries:

De Coemeterio. Cap V.

nulla pars coemeterii aedificiis occupata sit, nisi tempore hostilitatis. Crux decens et honesta, vel in ipso coemeterio erecta, ad quam fiet processio ipso die Palmarum, nisi in alio loco consuevit fieri.9

nulla pars coemeterii aedificiis occupata sit, nisi tempore hostilitatis. Crux decens et honesta, vel in ipso coemeterio erecta, ad quam fiet processio ipso die Palmarum, nisi in alio loco consuevit fieri.9

The graveyard cross was firmly linked to the celebration of Palm Sunday. When the dean of Sarum visited the chapel of St Nicholas in Earley, Berkshire, in 1224 he witnessed a Palm Sunday cross set to mark a plot of land in a (failed) attempt to make it into a cemetery.10 Palm Crosses became an integral part of the liturgical landscape of medieval England. Such crosses, however, had existed long before the Norman Conquest and the introduction of the Palm Sunday procession of the high Middle Ages. Still present in churchyards throughout the British Isles, they tower over their surroundings and are carved with narrative scenes, marking the place of preaching and worship.11 These sacred stone crosses did not originate with the post-Conquest liturgy, but were rather a remnant of its Anglo-Saxon past. They were incorporated into the route of the procession as a local interpretation for the meeting place of Christ and the welcoming crowd.

Palm Crosses served an important symbolic function. They grounded the biblical re-enactment in the landscape and provided a location both hallowed and familiar. At the next station, a marginal location in the Gospel narrative became central. Having met Christ by the Palm Cross, the combined entourage made its way to a city’s gate or a church’s west portal, where children s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- List of plates

- List of figures

- List of music examples

- List of tables

- Preface

- Note on transcription

- List of abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 The Bible and liturgy: Palm Sunday processions

- 2 The Bible as talisman: textus and oath-books

- 3 Paratext and meaning in Late Medieval Bibles

- 4 Preaching the Bible: three Advent Sunday sermons

- Conclusion

- Appendix: a survey of Late Medieval Bibles

- Bibliography

- Index