- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

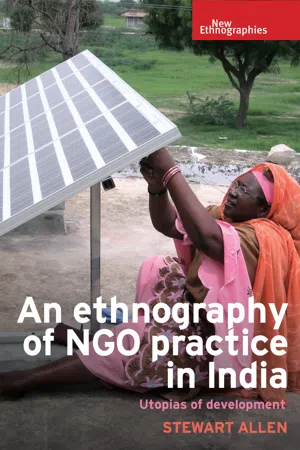

Through an ethnographic study of the 'Barefoot College', an internationally renowned non- governmental development organisation (NGO) situated in Rajasthan, India, this book investigates the methods and practices by which a development organisation materialises and manages a construction of success.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access An ethnography of NGO practice in India by Stewart Allen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Strands of history

‘Please understand, Your Excellency, that India is two countries in one: an India of Light, and an India of Darkness. The ocean brings light to my country. Every place on the map of India near the ocean is well off. But the river brings darkness to India—the black river.’

Arvind Adiga, The White Tiger, 2008

In The White Tiger (2008), Arvind Adiga's award winning novel of modern-day India and its rise as a world power, the protagonist, Balram, describes an India of binary opposites: one of progress, enlightenment and renewal represented by the ‘light’ of the urban spaces; the other of backwardness, superstition and want represented by the ‘darkness’ of the rural areas. These contrasting symbolic worlds have played a pervasive role throughout India's development in the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

The dichotomy of rural and urban India looms large in the consciousness and imagination of modern India, a land commonly portrayed as one of striking contrasts and polarised social cleavages. On the one hand, the economic ‘miracle’ of modern-day India is predominantly an urban miracle with approximately 60 per cent of GDP attributable to urban areas in 2008, estimated to rise to 70 per cent by 2030 (Sankhe et al. 2010). By 2030 it is further estimated that India will have sixty-eight cities with more than one million inhabitants, thirteen cities with more than four million inhabitants and six megacities with populations of ten million or more. The cities are the engines of economic growth and the hubs through which India's newly emerging globalised elite reach out to the rest of the world.

By contrast, the Indian village has long been viewed as the authentic signifier of traditional Indian social life, the beating heart of an ancient and contradictory land. As an ideological category and reference point by which nationhood and culture, values and purity have all been judged against the corrupting influences of modern life, the village is often referred to as the ‘real’ India and the ‘basic unit’ of Indian society. In the government census in 2011, the number of villages in India was put at 640,876, which contained 68.84 per cent of the populace.1

Indian villages have existed for thousands of years; however, it was during the British colonial era that villages were constructed as ‘village republics’ complete with qualities of autonomy, stagnation and continuity, ostensibly to help justify Britain's own case as foreign rulers to their subjects back home (Jodhka 2002: 3343). Since this time, as Jodhka (2002) notes, the idea of the village has continued to persist in the Indian imagination and has been employed by a variety of groups for different ends. The nationalist movement and, subsequently, leading political parties have invoked the village in different guises throughout the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. It is also the village that leading politicians today often visit to demonstrate their bond and empathy with ‘traditional’ India and the struggle and plight of its rural people. Gandhi is perhaps the most recognisable proponent of the Indian village, invoking it variously to critique the West and modern Western culture, and as an alternative way of living. Such commentaries have become popular with many environmental action groups and NGOs that have drawn from Gandhi's writings to propose alternative remedies to the country's social problems.

One such organisation that has persistently summoned the spirit of this rural-urban divide is of course the Barefoot College. The College has invoked, in various ways throughout its history, the imagery of the rural ideal and its sometimes-fraught relationship with the outside world. Through the summoning of these binary opposites, the College has sought to project itself as a forward-thinking, progressive, yet ultimately authentic space in contrast to a corrupt and globalised metropolitan imaginary. In the following chapter I argue that by situating itself within both places at once, equally rural and authentic, yet also modern and progressive, the College as a heterotopic space could exist outside the vagaries of time. Being of ‘no place’, neither past, present or future, but rather floating free above the fray, the College has been able to situate itself, at different times, within different development trajectories, altering its vision in line with changing political and economic concerns. In the process of this, through the implementation and reflection of a changing nationalist and development landscape, the College, I suggest, was able to navigate and in a sense, stay ahead of the game to ensure its success.2

Such imaginings are highlighted through the tripartite nexus of civil society/the market/the state and the entangled ways in which these institutions dynamically constitute one another. Through an outline of pre- and post-independence practices and policies of voluntarism and community development in India, I demonstrate how the College situated itself and became enmeshed within such trajectories. Through an examination of early documents, archival materials, official reports and media releases, I chart the organisation's development and growth as its founding members – urban educated doctors, teachers and engineers – experimented with different approaches and struggled with rural realities. What emerges is less a picture of a design in practice, and more a series of ad hoc trials and tribulations, the outcome of which is never lastingly determined, but rather shifts and transmutes over time and circumstance.

Pre-independence development: from philanthropy to resistance

Voluntary work in India can be traced back to the medieval period through the operation of social institutions in the fields of medicine, education and drought relief (Inamdar 1987). However, it was in the mid-colonial period from the early nineteenth century onwards that voluntarism really hit its stride when large-scale voluntary efforts were instigated by Christian missionaries and the philanthropy of the Indian bourgeoisie (Sen 1992). While their foremost goal may have been propagating Christianity, Christian missionaries were among the first organised groups to build schools, hospitals and orphanages for the uplift and benefit of the marginalised and socially excluded.

In Bengal the local bourgeoisie were among the first to be influenced by the philanthropic actions of the Christian missionaries and began a similar missionary drive, this time derived from both Hindu and Christian writings under the leadership of Keshab Chandra Sen. Sen was a young radical and disciple of Debendranath Tagore, one of the early founders of the Brahmo religion, himself a disciple of the social reformer Rammohun Roy (Jones 1989). Tagore revived Roy's reformist organisation Brahma Sabha, subsequently changing its name to Brahmo Samaj. It was Sen, however, who helped spread the reformist ideals of the Samaj throughout Bengal and beyond by establishing small hospitals, orphanages and leper asylums, and addressing issue-based social reforms such as the abolition of child marriage, education for women and remarriage for widows (ibid. 38). With a view to regulating and monitoring these new organisations, the colonial government enacted the 1860 Registration of Societies Act. As Sheth and Sethi (1991: 51) note, these new self-help philanthropic organisations increasingly acquired an anti-colonial political dimension as they became associated with social reform programmes, which in turn came to be understood as non-governmental.

From 1850 to 1900 a growing educated middle-class stratum and increasing nationalist consciousness led to the spread of ideas of indigenous self-help in opposition to colonial administered state development programmes. By the turn of the century, such sentiments were further stimulated through the Swadeshi movement and Gandhi's increasingly vocal championing of voluntary activity as the solution to rural poverty through self-governing, self-reliant village republics free of external influence and dependence (Sen 1992: 178).

By 1916 Gandhi had entered politics and began a series of strikes at Champaran Satyagraha in 1917 and Ahmedabad in 1918, culminating in his campaign of non-cooperation in 1920. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s Gandhi implored the youth of India to go out and work among the rural poor, the dalits and tribals (Sooryamoorthy and Gangrade 2001: 46).3 Gandhi's belief that India's heart lay in the villages inspired him to commit his energies to rural development, and he established a wide network of institutions, voluntary associations and social welfare programmes.

The outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 marked the beginning of the end of the British Raj after India was made party to the war without consultation. Mass walkouts by congress leaders followed. The successful Quit India campaign, launched in congress in 1942, convinced the British government of the strength and depth of the congress’ support base. With Britain left virtually bankrupt following the end of the war and resources stretched thin, an inevitability slowly built up, culminating in the Independence Act 1947 (Guha 2007).

Post-independence India: nation-building and integrated development

In the years that followed independence, from 1947 until the early 1960s, a newly independent India – under the leadership of Nehru – embarked upon a series of wide-scale planned development strategies with significant support from international donors, particularly the United States (Ebrahim 2003: 35). In contrast to Gandhi, who advocated decentralisation and the establishment of autonomous village republics, development under Nehru was understood as centrally planned economic progress and growth. Many such strategies were carried out by voluntary organisations already on the ground, broadly divided into those of a Gandhian bent and those founded on religious principles. As Sen (1992) notes, such groups can generally be described as providing development and empowerment programmes on the one hand, as the Gandhian organisations did, and welfare and relief efforts on the other. Gandhian groups tended to be involved in handicrafts, village industry projects and educational programmes, while religious groups were more likely to provide relief for flood and famine victims and the provision of health and nutrition programmes for the poor (ibid. 180). While religion-based groups were primarily motivated by religious philanthropy, the Gandhian groups were closely linked to the emerging policies of the new government and the establishment of new funding opportunities for development work, in particular the formation in 1953 of the Central Social Welfare Board (CSWB) for the administration of funds to these organisations (ibid.).

Sheth and Sethi (1991: 53) suggest that the reliance of many of these organisations on central government funding led, in large part, to the dissolution of difference between government social welfare programmes and these independent organisations, with many implementing official government projects through local political systems such as the Panchayati Raj. As such, this comprehensive stream of social-reform-based voluntary work, from health and education to disaster relief, has been described as a phase of nation-building whereby many of the targeted sectors were eventually assimilated and co-opted in official government strategies (Society for Participatory Research 1991).

From the early 1960s onwards, centrally planned development initiatives came under increasing scrutiny as a succession of untimely events led to disillusionment and comprehensive re-evaluations. The apparent failure of the ‘trickle-down’ theory of development manifested in a series of famines, inflations, rises in unemployment, political and social instabilities, and militant movements, which forced a radical re-think on government development policies (Sheth and Sethi 1991). Ebrahim (2003) notes that such events contributed to a move away from macro-level growth targets to those focused on the individual and meeting the needs of the identified poor. Changes in policy duly followed, the most noteworthy of which was the adoption of ‘Green Revolution’ technologies as India sought to become self-sufficient in terms of food supply, improvement of nutrition and the overall health of the populace.

This period also witnessed changing social and political conditions in many parts of India, including the defeat of congress in several state assemblies in 1967, the Naxalite uprisings in 1967–70, and an increasing divide between urban and rural areas (Society for Participatory Research 1991). This era was also notable for the implementation of new and alternative development models, most notably ‘integrated development’ in the late 1960s, which sought to develop communities from a more holistic perspective, focusing not only on economic initiatives but also on health, education and the environment. The independence of Bangladesh in 1971 also led to tremendous upheaval, prompting many young people to become involved in social and voluntary work. A growing student movement from 1967 to 1969 was given impetus by the National Service Scheme (NSS), which was launched in 1969 and provided support to newly graduated students wishing to work on a voluntary basis to help the poorer sections of society. It was against this background of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series page

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Series editor’s foreword

- Introduction: selling the Barefoot College

- 1 Strands of history

- 2 An award controversy

- 3 India is shining

- 4 Solar spectating: the witnessing of development success

- 5 Circuits of knowledge

- 6 Replication and its troubles

- Conclusion: the frayed edges of the spectacle

- References

- Index