No other city portrays the economic malaise and industrial unrest troubling Britain in the last quarter of the twentieth century more poignantly than Liverpool. This city and the surrounding Merseyside region had frequently been prone to labour strife since the dawn of organised labour. However, it was the emergence of Thatcherism and the ascent of neoliberal economics which placed Liverpool at the forefront of national protest against the encroaching tide of unfettered, free-market capitalism, swingeing cuts in public spending, privatisation of public services and the loss of British manufacturing. The spectre of spiralling unemployment was arguably the most pervasive feature which encapsulated the political economy and social fabric of Liverpool in the last three decades of the twentieth century. Consequently, it can be proffered that in this period joblessness and economic deprivation blighted Liverpool more than any other major British conurbation.

A perusal of archival sources chronicling reports from leading national news agencies illustrates this contention. Evidence of industrial unrest, public demonstrations, workplace occupations, civil strife and political protest can be found almost anywhere in Britain throughout the 1980s, but press reports seemingly focus on Liverpool specifically whenever public dissent was vented. Obviously, an empirical study examining the amount of protest occurring in which cities with the highest magnitude would be a difficult if not impossible task. This is especially true when one considers the major body of evidence available for such a study would have to be taken directly from media sources.

A more detailed comparative analysis will be addressed in the forthcoming chapters. Nevertheless, a brief insight from the archives of a leading national broadsheet show that during the same final twenty-five-year period of the twentieth century when Liverpool’s unemployed were becoming further politicised and mobilised, an attempt to organise the unemployed in Sheffield was also afoot.1 Unfortunately the effort in South Yorkshire failed in this instance, whereas in Liverpool it flourished. Indeed, there were also dispatches of factory occupations and sit-ins in Manchester, Bathgate and Preston during this time.2 Local council workers in Coventry attempted to close off public services in protest at wage and job cuts, just as had been accomplished in Liverpool.3 Nevertheless, the industrial action in Coventry did not result in the local council adopting a revolutionary platform of self-induced bankruptcy as had occurred in Liverpool.

Over 50,000 workers marched in Glasgow against rising joblessness, but some press reports made note of a lingering sense of apathy, despite the large turnout. They also painted a picture of suspicion from rank-and-file workers of their leadership who were ‘strong on rhetoric’ but lacking in details of how they planned to bring back full employment.4 Amongst these notices there were a number of pieces criticising the unusual degree of worker indifference present during this period, with headlines such as ‘Why the unemployed are not in revolt’, ‘March for jobs against apathy’, ‘A generation fuelled by apathy’ and ‘Bitterness, resignation and dwindling hope’, to name only a few.

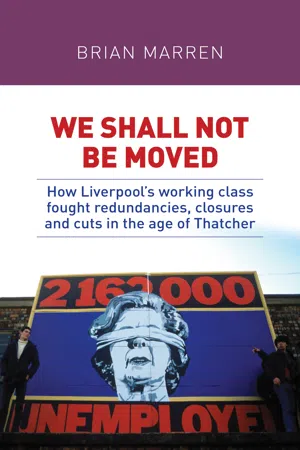

It is interesting, however, that the lion’s share of articles focusing on working-class militancy within Liverpool at this time make little mention or hints of a similar sense of resignation and defeat.5 Indeed, one piece plays into the ‘cheeky chappy Scouser’ stereotype in a report of how some 1,200 soon-to-be idled workers from Liverpool’s Tate & Lyle sugar refinery burst into a rousing rendition of ‘We shall not be moved’ as a sign of their refusal to accept job losses and the plant’s closure.6 Typically, this overly caricatured portrayal of Liverpool in the national media was more common than not. Therefore, when judging the militancy of the region’s workforce, press reports alone do not offer the full insight necessary that such a comparative analysis requires.

Furthermore, there is no doubt that the policies of the Thatcher government and the corresponding de-industrialisation of the British economy had an enormous impact on working class communities in every British city. This analysis would never claim otherwise. However, it will note that Liverpool’s unique history made it particularly vulnerable to such changes, and because of this, the working class of Liverpool reacted against this further intensification of capitalism in a particularly vocal and aggressive manner when compared to plebeian elements in other provincial British cities.

The central concern of this book will be an analysis of the range and depth of organised reaction from large segments of Liverpool’s working class to the many forced redundancies, factory closures and sweeping government cuts in this era of post-industrial decline. It is centred in a time when the neoliberal economic model and Thatcher’s own brand of monetarism were pursued by the British establishment as an elixir for what many saw as a failed experiment in cross-party consensus during the immediate post-war era, culminating in thirty years of a welfare state and Britain’s first and only dalliance with social democracy.

Neoliberalism emerges as a challenge to the post-war settlement

The battle lines between the forces of collectivism and the proponents of the free market had been drawn long before the ascension of Margaret Thatcher as leader of the Conservative Party in 1975. By the late 1980s, with the fracturing of the left and the neutering of the trade unions it became obvious that neoliberalism had won that war. The political right’s campaign against forces supporting collectivism and social democracy was a long-lasting crusade, and Liverpool often found itself to be in the centre of that conflict.

Nevertheless, the clash between capitalism and socialism, between supporters of the free market versus those who advocated a mixed economy, simmered long before it finally exploded in 1979 with the election of the Tories under Margaret Thatcher. The great ideologies of this struggle were represented through the writings of such economic luminaries as Friedrich Hayek on the right, and John Maynard Keynes representing the centre-left. For the first thirty years of the post-war era, it was Keynes who held the upper hand in both British and American politics.

By 1945, after suffering for over three decades from the horrors of two global wars and the destitution of the Great Depression, even ‘conservative’ Britain coveted a radical transformation from the past. The inter-war slump taught many within the British establishment that capitalism had its limits, just as they learned through the war about the positive benefits gained through state planning, collectivism and collaborating with labour. After the peace, most British political leaders recognised that a level of consensus was necessary in order for Britain to rebuild itself, even if that included working within a mixed economy. Maintaining efficient levels of production, balance of payments and industrial output were, of course, key factors if a post-war rebuilding programme had any chance of success.

It was without precedent, but there was at this time majority support for a planned commitment to full employment. It was vowed that work for every hand was to be considered as much a priority for the labouring classes, as profit was for capital. Government would take the bold step of intervening against market forces, if necessary, to ensure such full employment. The election of a Labour government in 1945 inaugurated this arrangement. What followed was thirty years of cross-party commitment towards social democracy, the welfare state and a mutual acceptance of the mixed economy. The arrangement that emerged in 1945 not only pledged full employment as a priority, but there were also provisions made for a national health service, limited public ownership of certain key industries and some semblance of centralised economic planning. A promise to reduce the old vestiges of class privilege also took on a new level of importance.

Trade unions were granted an important role within the new post-war plan. Trade union leaders were included in the decision-making process of economic policy, and their input was sought by both Labour and Tory governments. The security of full employment lent greater autonomy to local trade union branches, and ultimately, more shop-floor democracy via the empowerment of shop stewards – the lowest ranking union official, but nevertheless the face of trade unionism on the factory floor.

From 1945 to 1979, both Labour and Conservative governments would introduce legislation periodically, which diverted or removed the will of market forces. Keynesianism became the prevailing orthodoxy of the period. Unlike Marx, Keynes did not advocate an alternative to capitalism. Indeed, for Keynes the problem was not capitalism itself, but simply ‘laissez-faire’ capitalism. It was his belief that unregulated markets had the potential to destroy capitalism if they were left to the selfish pursuit of profit without any care for the rest of society. Keynes’ belief in the need for ‘responsible capitalism’ was entrenched in his opus The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money.7 Most trade union leaders, often having to answer to the concerns of both sitting governments in Westminster and their rank-and-file, were satisfied with the post-war arrangement and found Keynesianism a tolerable form of controlled capitalism.

Friedrich Hayek, however, in his pivotal work The Road to Serfdom, posed a counterpoint to this arrangement.8 Rather than controlling markets, Hayek insisted the market must be unchained and left to the free-flowing natural order of the ‘invisible hand’. Hayek maintained that it was government meddling in the money supply which increased inflation and depressed corporate profits. According to Hayek all such diversions distorted the market, leading to a continuous crisis of boom and bust, built largely on fictitious capital.

However, just as many on the British left were wary of the absolute dictums of pure Marxism, opting instead for the mixed, social-democratic approach of Keynes, the political right in the UK preferred Hayek only in half-measures. More important to the shaping of neoliberalism, as it metastasized itself in Britain, were the lessons of the Nobel Prize winning economist Professor Milton Friedman, and his circle of followers from the University of Chicago. It was not until the early 1970s when the work of Friedman came into vogue amongst the British right. And only then did neoliberal economic theory gain a sizable momentum in the UK.

The term neoliberal became synonymous with the teachings proffered by Friedman and his colleagues in Chicago. Like Hayek, Friedman and his associates at the University of Chicago extolled the freedom of the individual, they advocated free trade, demanded deregulated markets, celebrated entrepreneurial pursuits, believed in heightened privatisation of public services and less government involvement in personal space. They rejected collectivism in most forms and scorned ‘entitlements’ and the fostering of a ‘dependency culture’. However, unlike Hayek, Friedman and the Chicago School believed the government needed to maintain a role in regulating the central bank and money supply. The Chicago School argued inflation was far more devastating to capital than unemployment. It, therefore, had to be harnessed at all costs: even if that meant sacrificing struggling industries and well-paid blue-collar jobs. In their view, any government that obligated itself to maintaining full employment was part of the problem, not the solution.

The neoliberal model, while radically libertarian in some respects, still derived much of its strength through a veneration for traditional structures such as a strong military presence and strict maintenance of law and order. Combined with a pragmatic approach towards increasing corporate yield, neoliberal ideology ingratiated itself with conservative movements, searching for ways to adapt to the changing nature of the modern world. It promised greater corporate revenues while simultaneously stoking the fires of traditionalism on one hand and individualism on the other.

Furthermore, committed neoliberals argued that allowing the market free rein, unencumbered by government regulation and human manipulation, was the only way to guarantee the economic freedom necessary that could procure political democracy and civil liberty on a global level. Encouraging words, indeed, to many staunch Cold War warriors and corporate chieftains alike. Thus, it was Friedman, and not necessarily Hayek, who won the heart of Tory politicians on the growing right-wing of the Conservative Party such as Sir Keith Joseph and Margaret Thatcher. Neoliberalism was sold to voters by equating its ideals with such cherished Anglo-American values as liberty, individualism and patriotism.

Historians of the Thatcher era have proffered that neoliberalism evolved in Britain through a series of distinct stages.9 Originally, the ideas tendered by Hayek served more as an oppositional philosophical argument to Keynesianism and the evolving post-war consensus, rather than as a strict structural system of administrative governance. However, by the early 1970s as economic volatility grew more apparent due to embedded inflation becoming aberrantly pai...