- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Analyses the phenomenon of literary disenchantment after the First World War

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Writing disenchantment by Andrew Frayn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Social History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Patriotism, propaganda and pacifism, 1914–1918

The expression of disenchantment in wartime was difficult: any challenge to orthodoxies, official and officially sanctioned discourses was most often made from an already dissenting position. People marginalised by gender, sexuality, politics, religion and profession spoke out against the war; rarely did establishment figures show dissent. The small number who chose not to participate in the war effort showed their disenchantment by not fighting or, in the case of women and men officially disbarred from combatant service by age or physical condition, by refusing to labour in its service. In this chapter I discuss the ways in which literary texts react against official narratives. The alterity of dissenting voices allows publication, but also suggests they can be disregarded. I understand official narratives broadly to mean both explicitly sanctioned work such as propaganda, laws, official war reports and other texts which are in sympathy with governmental aims, objectives and language.

Max Weber points to the role of reportage in demotic language in fostering community. In war it also purports to provide information:

The importance of language is necessarily increasing along with the democratization of state, society, and culture. For the masses a common language plays a more decisive economic part than it does for the propertied strata of feudal or bourgeois stamp. […] Above all, the language, and that means the literature based upon it, is the first and for the time being the only cultural value at all accessible to the masses who ascend toward participation in culture.1

As the state is democratised and, notionally with it, services such as education and political representation, there comes a need for effective mass engagement. The democratisation of communication is also the disenchantment of faith, and the beginning of a challenge to the old orders. Patrick Brantlinger sees the mass media as complicit in perpetuating social decline.2 Where religion was previously mostly unifying, mass forms begin to provide an alternative shared language, although the hegemony of conservatism and church is slow to dwindle. Oswald Spengler explicitly characterised the press as another form of war technology: ‘Gunpowder and printing belong together – both discovered at the culmination of the Gothic, both arising out of Germanic technical though – as the two grand means of Faustian distance-tactics’ (DW, 2, 460). The press is equally culpable as long-range artillery, and has perhaps even greater power to shape narratives of war: it is not a coincidence that Marshal Joffre and Field Marshal Haig disliked the press.3 Equally powerful are the texts that are given official sanction in other ways, such as the rousing, patriotic poetry of Rupert Brooke, Julian Grenfell and others, discussed in the Introduction, and Horatio Bottomley’s patriotic magazine John Bull.

There was not initially such a clear mandate for war as early studies of the conflict supposed: patriotic fervour was limited, and influential newspapers such as the Manchester Guardian initially opposed the war.4 However, when war became inevitable even the Manchester Guardian, which had opposed the Boer War throughout, fell into line. There were doubts about the validity of the war, but there was a clear sense that it must be supported fully and effectively,5 drawing on the British love for the underdog to defend ‘little Belgium’ just as that principle had been evoked to stimulate recruitment for the Crimean War sixty years earlier.6 Adrian Gregory states that ‘it provided both an excuse, and a cover, for the Liberals who had already decided that Germany should be resisted.’7 The war was justified as a defensive war in favour of freedom and civilisation, honourably carrying out Britain’s treaty duties in the face of Prussian militarism. The mobilisation of the British Army was just as successful an act of militarism, drawing on the enchantments of the public school spirit discussed in the Introduction. The recent creation of proto-militarist, muscular Christian organisations such as the Boys’ Brigade (1883) and Robert Baden-Powell’s Scout movement, whose bible Scouting for Boys (1908) was a bestseller throughout the twentieth century, meant that a generation of boys was indoctrinated with the values which defined the British Empire; the Girl Guides promoted similar values, with an emphasis considered appropriate for young Edwardians. The propagation of knightly virtues was reinforced by the stories of derring-do and adventure in the Boy’s Own Magazine (1855–90), the more successful and enduring Boy’s Own Paper (1879–1967) and their derivatives.8

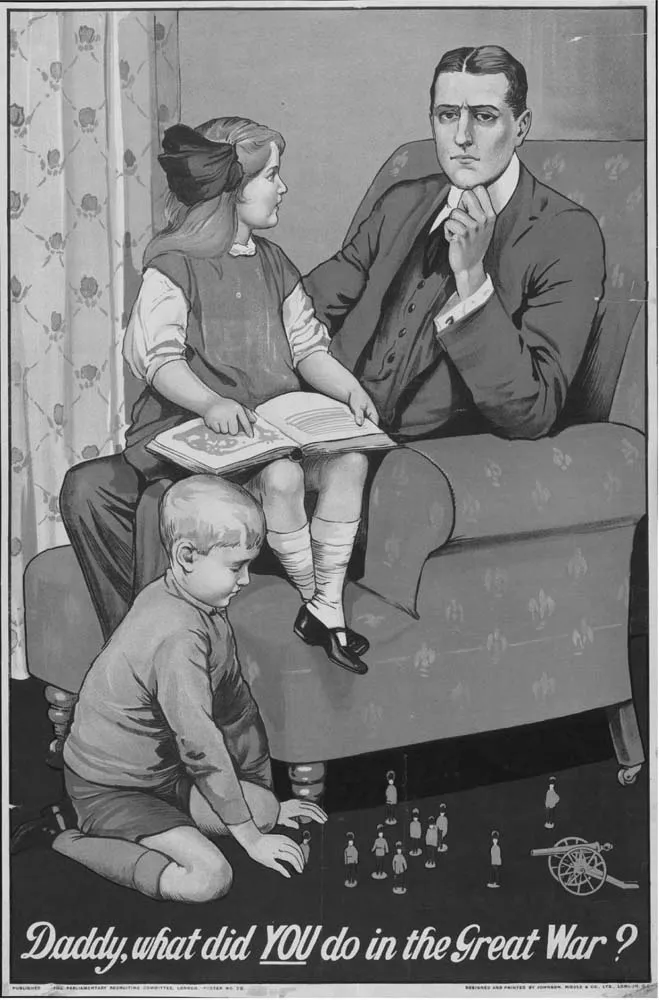

Propaganda emphasised heteronormative masculinity and femininity. Military recruitment posters tended to separate male, public and active, and female, domestic and passive, in such slogans as ‘Women of Britain say – “Go!”’ There was a significant degree of intersectionality between pacifism and other marginal groups such as feminists, socialists, artists, homosexuals and Jews. Any expression of pacifism stood out in wartime, and unofficial social enforcement ensured that such publications were by and for marginal groups. Challenges to the system and the way the war was being conducted looked increasingly well-founded as the war continued; consequently, they were increasingly the subject of censure as the need to continue fighting was reasserted. Culture was scrutinised carefully, and private letters written by serving soldiers were subject to censorship. The army circumscribed individuality by the Field Service Post Card, which allowed only pre-filled comments: no additional text could be appended.9 Angela K. Smith observes that during wartime: ‘Private writing [… is] built around the empty phrase and the euphemism, entrapped and lifeless within a hollow discourse.’10 This is certainly true, but the hollowness is necessary to provide a space which can be filled imaginatively by the reader on the understanding that there were things which were better not and could not be said. In the post-war decade John Masefield asserted that ‘the events of all wars are obscure; history is only roughly right at the best. The events of this last war will be more obscure than those of most, because of the power of silencing opinion and hiding facts possessed by those who waged it.’11 A notable example was C. R. W. Nevinson’s painting ‘Paths of Glory’, depicting dead Tommies, which was banned from his Leicester Galleries exhibition.12 In Rose Macaulay’s Non-Combatants and Others, discussed below, the protagonist Alix notes that ‘Painting and war don’t go together’ (NC, 33). However, context was all; newspapers did not shy away from publishing photographs of the front lines, but when framed as artistic interpretation, a more explicit attempt to create affect in the audience, such images were unacceptable.13 John Horne describes censorship as ‘a negative means of safeguarding security and promoting consensus’, and notes the greater state control over art during wartime.14 That control continued after the war: novels about the war comment on events which had been subject to extreme official control, of which vestiges endured.

Wartime prose both reinforces and poses challenges to such narratives. I take as brief case studies the renowned propaganda posters about the war and Ian Hay’s The First Hundred Thousand (1915), which extols the virtues of the training camp; against those I set Ford Madox Ford’s official works of propaganda, which show support for the war effort without resorting to jingoism. I then show the polyphonic nature of wartime novels, both those which ultimately advocate the necessity of continuing to fight, focusing on H. G. Wells’s Mr Britling Sees It Through (1916) and his lover Rebecca West’s The Return of the Soldier (1918), and those which offer more ambivalent assessments, such as Rose Macaulay’s pacifist Non-Combatants and Others (1916) and Rose Laure Allatini’s Despised and Rejected (1918), which discusses pacifism and conscientious objection. Allatini’s novel was published under the pseudonym A. T. Fitzroy, and in late 1918 it was banned for hindering the war effort.

Patriotism and propaganda: mobilising Britain

The hegemonies that propaganda bolsters are retrenched by marginalising criticism and circumscribing challenges to official discourses by legal and covert means.15 The focuses for First World War propaganda are summarised by the two best-known posters of the war, which address national identity, gender and age. Lord Kitchener’s penetrating stare from beside the slogan ‘Your country needs you’ invokes a language of duty which draws on the Christian moral code and vestiges of hierarchical feudal loyalty, but also the ability of the nation to ‘inspire love, and often profoundly self-sacrificing love’.16 In the other, the child’s question ‘Daddy, what did YOU do in the Great War?’ (Figure 1.1) puts pressure on the father to avoid exclusion from a defining shared masculine, patriarchal experience, and emphasises his duty to protect. The gender identities of the children are distinct: the boy is preparing for military service, playing with soldiers and cannon on the floor, while the submissively domestic, immaculately coiffed girl sits on her father’s lap to read. Cate Haste states that ‘the essence of propaganda is simplification’, and women did valuable war work, most visibly making munitions, but this could not appear in posters which encouraged men to enlist.17 The possibility of return to a stable national and domestic environment had to be maintained. The father’s role as protector is asserted, but in later disenchanted fiction such as Richard Aldington’s Death of a Hero the Victorians, the absent grandparents of this picture, are often held responsible for creating the world which led to the war and allowed it to endure.

Figure 1.1 ‘Daddy, what did YOU do in the Great War?’

Propaganda was understood immediately as a literary endeavour, and one of the men who participated in the pre-war discourse of disenchantment was given the responsibility for its organisation. The irony of C. F. G. Masterman’s appointment as head of the War Propaganda Bureau run from Wellington House is compounded by the fact that, as Mark Wollaeger points out, ‘by rallying support for the war on idealistic grounds he ultimately contributed to the disillusionment of the postwar years’.18 One of Masterman’s earliest actions was to call together, on 2 September 1914, twenty-five high profile authors including critically and popularly acclaimed people such as J. M. Barrie, Arnold Bennett, John Galsworthy, Thomas Hardy, H. G. Wells and the Poet Laureate Robert Bridges. A meeting with influential newspaper editors and publishers quickly followed. Masterman himself wrote in 1915 stressing the achievement of Britain and the need for endurance and fortitude in preparation for a long war.19 Not only did Wellington House produce literature and journalism, it also operated in the new medium of cinema and produced such diverse materials as picture postcards and translations of official reports.20 Propaganda centred on the combination of prose and images. The cinema was still silent, although The Battle of the Somme (1916) ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures

- Acknowledgements

- List of abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Patriotism, propaganda and pacifism, 1914–1918

- 2 From hope to Disenchantment, 1919–1922

- 3 Modernism, conflict and the home front, 1922–1927

- 4 Sagas and series, 1924–1928

- 5 Popular disenchantment: the War Books Boom, 1928–1930

- Conclusion

- Select bibliography

- Index