eBook - ePub

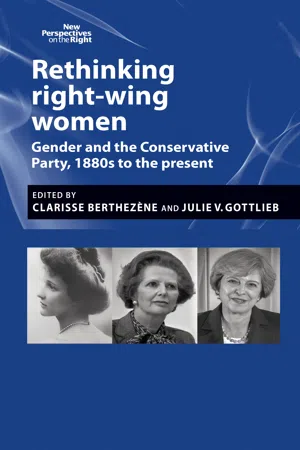

Rethinking right-wing women

Gender and the Conservative Party, 1880s to the present

- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Rethinking right-wing women

Gender and the Conservative Party, 1880s to the present

About this book

Rethinking Right-wing Women traces the mobilization of women for the UK Conservative Party from the period before their enfranchisement to Theresa May. As party workers and organisers, MPs and leaders, and as voters, women have been fundamental to the success of the Conservative Party.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Rethinking right-wing women by Clarisse Berthezène in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politica e relazioni internazionali & Politica comparata. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

‘Open the eyes of England’: female unionism and conservatism, 1886–19141

Diane Urquhart

Women were often active agents of change. Their involvement in elections, political protests and petitioning pre-dated the establishment of formal women’s political associations in the 1880s and partial female enfranchisement in 1918. Women could, and did, influence the voting practices of men and female political writings were commonplace, although they frequently obscured their identity by the means of pseudonyms or anonymity which raises the question of gendered political boundaries. Involvement in national reform campaigns for married women’s property rights, women’s suffrage, the repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts and Irish land reform also prompted Irish and British female political cooperation in the mid- to late nineteenth century.

However, social class often dictated the type of political activity women could perform with the upper-class political hostess typifying the heady influence that some women exerted as conduits between the conjoined socio-political domains of the Victorian and Edwardian eras. Yet, despite the visibility of politically active women, they have often been understudied and excluded from histories of party and popular politics. In relation to conservatism and unionism, this lacuna minimised considerations of women’s political contribution and led to both ideologies being depicted as largely and – at times – wholly male manifestations.2 Women are being written back into these histories and it is an indication of the maturity of women’s history that the female Unionist movement can now be placed into a broader backdrop of popular conservatism. A gender inclusive approach also allows for a more nuanced understanding of political machinations, power and the unprecedented popularity of both conservatism and unionism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Women were drawn into more formal political associations not by any evolutionary process from their early political activism, but by a combination of party self-interest and the impending political crisis over Irish home rule. Conservatives were conscious of the need to widen their support base beyond the traditional rural heartland by the early 1880s, but the Corrupt and Illegal Practices Prevention Act of 1883 had a more pressing impact on the need to popularise conservatism. This Act inadvertently changed the political worth of women as party workers. Expectations of the Act were high as it was hoped that it would ‘work well in the interests of electoral purity’ to establish ‘a new form of electioneering law’3 and ‘confer upon the constituencies much greater freedom in the choice of candidates’.4 Despite the passage of the Corrupt Practices Act of 1854 and the Ballot Act of 1872, the 1880 election saw eighteen members unseated, owing to electoral corruption, and cumulative electoral expenses were estimated at £2–3 million.5 Many thus welcomed the 1883 Act which forbade treating, undue influence, bribery, personation and the payment of canvassers and workers taking voters to the polls or posting electoral posters.6 The number of electoral agents, meetings and expenditure was also tightly regulated by constituency size. Fines, imprisonment, bans on voting and candidature were the fate of those who attempted to evade its strictures.

However, from the Act’s passage in September 1883 there were concerns that it would be violated or, to use the press’s more colloquial expression, that the ‘proverbial four-horse coach will be driven’ through it.7 There was also consternation regarding the practicalities of levelling political expenses: ‘the rich man’ was still in possession of ‘an enormous pull over his poorer neighbour … but it [the 1883 Act] seeks to interpose an effectual barrier to the production of swollen election bills’.8 Candidates could still amass £100 personal expenses during electoral contests and, as the Trades Union Congress averred, more support might have been forthcoming for Labour candidates. However, a Commons’ motion to pay Labour candidates’ expenses from the rates was defeated by 167 to 80 votes.9 There were further charges of undue state influence with ‘many’ reportedly ‘afraid of legislation of this kind getting too “grandmotherly”’.10 The press’s adoption of this female idiom underscored the widely held view of women’s political unsuitability. The Act, however, also impacted on political party organisation beyond that likely envisaged by its Liberal sponsors; women were quickly encouraged to become politically active on an unprecedented scale.

As Rix suggests, the ‘obvious solution’ to the electoral conundrum posed by the 1883 Act was to augment existing party organisations, but this too had its critics. Many Conservatives were ‘suspicious of the much-reviled caucus’ and the associated curtailment of candidates’ independence. To the Saturday Review, for example, candidates would become ‘practically the slaves of local associations’.11 Some Conservatives also believed that the Liberals would benefit more from increased volunteer political labour, but this proved ill-founded. Any remaining Conservative misgivings on popularising the party association were also countered by the increase in the electorate in 1884 and their subsequent electoral defeat in 1885: the percentage of enfranchised adult males in England and Wales rose from 18.1 per cent in 1861 to 62.2 per cent in 1891 and in Ireland, over the same period, from 13.4 per cent to 58.3 per cent.12 Conservative expediency thus led them to form the first politically inclusive organisation. This was the Primrose League, established as a male-only association in November 1883, but women were admitted to its ranks in the following month. The reach of this new body thus went beyond the enfranchised and the elite; it was a defender of tradition with a clear attachment to the Anglican Church, monarchy and empire.13

Using a potent mix of imperialism, heraldry and Masonic modelling, Primrose League habitations (the name for male, female and mixed-sex branches) with male Knights, female Dames and Junior Leagues of ‘Buds’ became the largest party association. In 1884 its membership comprised 747 Knights and 153 Dames; by 1891 it recorded 63,251 Knights, 50,973 Dames and 887,068 associate members and by 1899 it had a million and a half members.14 Some degree of inflation was caused by the organisation’s practice of including lapsed members in its figures, but its entertainments were hugely popular although Lady Salisbury expressed this somewhat differently: ‘Vulgar … of course it’s vulgar. But that is why we have gone on so well.’15

The role of women within the League was carefully defined from the outset and these gender boundaries were rarely breached. This built on women’s earlier philanthropic work, political hostessing and involvement in bodies like the Anti-Corn Law League, which was ‘conceptualised as an extension … of domestic concerns, not as an intrusion into the ‘male’ political arena’.16 The led to domesticity being foregrounded for Primrose League Dames. In consequence, women’s work centred on political education, canvassing and ‘political sociability’ which developed ‘into a strong associational culture’.17

Owing to Lord Claude Hamilton’s initiatives, Irish Unionists formed a distinct grouping within the Conservative Party from 1886.18 An unwavering attachment to notions of a ruling elite, monarchy and especially empire also placed the Primrose League firmly within the Unionist camp. With Randolph Churchill, author of the ‘Ulster will fight, and Ulster will be right’ mantra, as a key League promoter, links to the augmenting Unionist campaign of the 1880s were perhaps inevitable.19 Theresa, 6th Marchioness of Londonderry also typified the connection between conservatism and unionism. This leading Conservative hostess, Primrose League Dame and member of its executive committee, was later president of the Ulster Women’s Unionist Council (UWUC). Her portrayal of the Conservative’s Party’s defining principles as Anglicanism, education and opposition to Home Rule further underscores the affinity with unionism.20 The Irish question was also, at times, ‘an excellent recruiting sergeant’ for the Primrose League; Pugh estimates that the first home rule bill and the Nationalist plan of campaign increased membership by 550,000 in the twelve months from March 1886.21

The League was also active in Ireland. By 1888 there were thirty-five Irish Primrose League habitations. However, the three Belfast habitations, which were in operation in the 1890s, constituted a third of the total Ulster representation. Indeed, the League was never overly popular in the heartland of unionism, the north-east of Ireland, where it faced competition from indigenous male and female Unionist associations as well as the Orange Order.22 By comparison, there was an identifiable Primrose concentration in the south and west of Ireland. Membership and gender profiles are not clear for all habitations, but few of the Ulster branches shared the popularity, albeit self-proclaimed, of St Patrick’s in Cork, with over 3,500 members in 1888. This was one of eight local Cork habitations, comprising 23 per cent of the total Irish branches, which established this city as the Irish centre of the Primrose League.23

There was a clear identification with the Unionist cause in the Irish habitations. In 1902, William Ellison Macartney, Conservative MP for Tyrone, addressed those attending a mixed-sex meeting of the Kingstown habitation in Co. Dublin as Unionists: ‘Every one of them was imbued with the principles of loyalty to the person of the Sovereign, and also to the Constitution.’ Yet, they were also branded as imperialists with a duty to support the government in bringing the Boer conflict to a successful conclusion despite the same administration having ‘neglected’ Ireland: ‘whatever legislation had been passed for Ireland, was, so far as it affected Unionists, to their detriment’.

The bulk of Macartney’s address, however, exhibited a preoccupation with maintaining the union and Irish affairs: land agitation; municipal politics and the Nationalist United Irish League.24 As such, his address underlined a variation in right-wing political priorities as interest in unionism outside of Ireland waned from the 1890s to such an extent that Henderson Robb claims that the ‘public bored’ of home rule.25 This is not without foundation; interest in the home rule issue temporarily diminished after the defeat of the first and second Home Rule bills in 1886 and 1893 and a heightened imperialism was evident in many English Primrose...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of figures and tables

- Notes on contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Clarisse Berthezène and Julie V. Gottlieb

- 1 ‘Open the eyes of England’: female unionism and conservatism, 1886–1914: Diane Urquhart

- 2 Christabel Pankhurst: a Conservative suffragette?: June Purvis

- 3 At the heart of the party? The women’s Conservative organisation in the age of partial suffrage, 1914–28: David Thackeray

- 4 Conservative women and the Primrose League’s struggle for survival, 1914–32: Matthew C. Hendley

- 5 Modes and models of Conservative women’s leadership in the 1930s: Julie V. Gottlieb

- 6 The middlebrow and the making of a ‘new common sense’: women’s voluntarism, Conservative politics and representations of womanhood: Clarisse Berthezène

- 7 Churchill, women, and the politics of gender: Richard Toye

- 8 ‘The statutory woman whose main task was to explore what women … were likely to think’: Margaret Thatcher and women’s politics in the 1950s and 1960s: Krista Cowman

- 9 Conservatism, gender and the politics of everyday life, 1950s–1980s: Adrian Bingham

- 10 Feminist responses to Thatcher and Thatcherism: Laura Beers

- 11 The (feminised) contemporary Conservative Party: Rosie Campbell and Sarah Childs

- 12 Conserving Conservative women: a view from the archives: Jeremy McIlwaine

- 13 Women2Win and the feminisation of the UK Conservative Party: Baroness Anne Jenkin, introduction by Sarah Childs

- Index