- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Full participation is the first book-length study of compulsory voting to be published in the English language. The volume provides a comprehensive description, analysis and evaluation of an institution that is becoming increasingly attractive in the context of declining rates of electoral participation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Full participation by Sarah Birch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Mezzi di comunicazione e arti performative & Storia e critica del cinema. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Why compulsory voting?

Why write a book on compulsory voting? A total of 29 countries in the contemporary world legally oblige their citizens to participate in elections, including about a quarter of all democracies. Yet in many voluntary voting states, the common view of this institution is of an outdated and largely disused relic from the past that will eventually disappear altogether as voters flex their liberal muscles and struggle to free themselves from all forms of compulsion. In fact, this view is distinctly at odds with much contemporary political thought, which is increasingly coming to see rights and duties as going hand in hand. Moreover, in many states where participation in elections remains voluntary, falling turnout has led a growing number of voices to call for making it a legal requirement. In 2006 alone, three major reports were issued on the subject in the UK–by the Electoral Commission, the Hansard Society and the Institute for Public Policy Research (Ballinger, 2006; Electoral Commission, 2006; Keaney and Rogers, 2006). The situation is similar in countries such as France and Canada, where prominent members of the political élite have recently called for electoral participation to be made mandatory.1 The fact that compulsory voting has recently received so much attention from practicing politicians suggests that the time is ripe for a scholarly review of the institution.

Oddly, there has not been a single English-language monograph on compulsory voting in over 50 years.2 This is not to say that the topic is not studied; it has been the subject of a range of scholarly journal articles (as detailed in subsequent chapters), and it is touched on in literatures as diverse as those on wealth inequality and support for the far right. Yet compulsory voting tends to be studied mainly in the context of analyses that have other principal objects of investigation.

This volume aims to fill this gap in the scholarly literature by providing a detailed overview of the history, practice, causes and effects of the legal obligation to vote, as well as an analysis of the normative arguments surrounding it. Recent debates about the possibility of introducing mandatory voting in those states where going to the polls remains voluntary call for a detailed discussion of the normative advantages and disadvantages of this institution. If compulsory voting is ever to be introduced in any of these polities, the normative debate will have to be won; it is thus useful to have a clear understanding of the various arguments for and against compulsory voting. One of the main functions of this study is thus evaluative.

A second main function of the book is explanatory. Compulsory voting has been introduced in a variety of contexts to address a range of problems, from low turnout in Belgium in 1893 to electoral corruption in Thailand over a century later in 1997. Yet the focus of most academic literature on the subject has been on the question of turnout alone. This volume seeks to broaden the study of compulsory voting by elaborating the effects it is frequently held to have, and by systematically examining each of these effects against comparative evidence from around the world. Compulsory electoral participation significantly alters the incentive structures faced by all the actors in the electoral arena, from parties and candidates, to voters, to electoral administrators. Its proponents and detractors alike have pointed to a range of likely impacts on the way elections are carried out, on the choices that are made at election time by key actors, and the effects of electoral results on wider political outcomes. At the same time, there has been scant effort systematically to examine these conjectures in the light of empirical evidence. The investigation to be undertaken in this volume will thus seek to elucidate the impact of the institution on phenomena such as political engagement, party strategies, electoral integrity, electoral outcomes, and policy outcomes.

Before moving on to these tasks, however, it is necessary to specify what exactly is meant by the term ‘compulsory voting’. That will be the role of this opening chapter, which will seek to conceptualise and construct a typology of electoral obligation, before examining variations in the way the institution of compulsory voting has been implemented in different states. The chapter will conclude with an overview of the structure of the book.

What is in a term?

Compulsory voting can be defined very simply as the legal obligation to attend the polls at election time3 and perform whatever duties are required there of electors. As is often recognised, the inherent constraints of the secret ballot mean that in most modern democracies (and even in many less-than-democratic settings) compulsory voting is, strictly-speaking, impossible. The state cannot typically monitor the behaviour of the elector in the privacy of the polling booth and can therefore do nothing to prevent him or her from casting an invalid or blank ballot; in very few states is any legal effort made to do so.4 The Dutch language recognises this distinction by employing a term – opkomstplicht – which can be translated as compulsory (or obligatory) attendance at the polls,5 as does a recent Institute for Public Policy Research Report, which refers to ‘compulsory turnout’ (Keaney and Rogers, 2006). Most European languages fail to make this distinction, however, and use terms that translate roughly as ‘obligatory voting’. The French speak of le vote obligatoire, the Italians of il voto obbligatorio, the Spanish of el voto obligatorio and the Portuguese of o voto obrigatório. In German the terms employed are (gesetzliche) Wahlpflicht and Stimmpflicht, while most Slavic languages use variations on the Polish term głosowanie obowiązkowe.6

The terms ‘obligatory voting’ and ‘mandatory voting’ do make their appearances in the English-language literature, yet the most commonly used term to designate this practice is ‘compulsory voting’. This is somewhat unfortunate, given the pejorative connotations of the term ‘compulsion’ in English; certainly ‘obligation’ has a rather different sound. Use of the term ‘compulsion’ thus casts the institution in a negative light in many English-languages debates on the subject (despite the fact that the Australians have been happily using this term to describe their electoral system for over 80 years). This usage has the further consequence of precluding an automatic semantic link between the institution and the broader notion of political obligation. A more appropriate term might be ‘the legal obligation to participate in elections’, but this being cumbersome, the present study will employ the terms ‘compulsory voting’, ‘mandatory voting’, ‘compulsory electoral participation’ and ‘mandatory electoral participation’, which will be used interchangeably.

Conceptualising compulsory voting

As has long been recognised by electoral behaviouralists, there are a wide variety of factors that bring people to the polls. We can conceptualise the incentive to vote as falling into two broad categories; pull and push and factors. ‘Pull’ factors include the standard range of motivations for voting, including the desire to influence electoral outcomes, expressive aims, identification with political contestants, and perceptions of civic duty (e.g. Campbell et al., 1960; Riker and Ordeshook, 1968; Verba et al., 1978; Powell, 1980; 1982; 1986; Crewe, 1981; Rosenstone and Hansen, 1993; Dalton, 1996; Franklin, 1996; 2002; 2004; Gray and Caul, 2000; Blais, 2000; Norris 2002; 2004). The legal obligation to vote is a principal ‘push’ factor; voters are urged to the polls by the law, with the threat of sanctions if they do not comply. Yet there are also other types of pressure that can be exerted to encourage people to vote, including social and political influence which, operating outside the ambit of formal political institutions, can nevertheless be remarkably effective. Indeed it is through this type of pressure, rather than legal compulsion, that the highest known turnout rates have been achieved in the world – the USSR’s regularly reported 99.99% levels of electoral participation (Bruner, 1990).7 Coercive mobilisation may also take the form of undue influence by political parties (see Cox and Kousser, 1981; Hasen, 2000; Lehoucq 2003). Finally, ‘ordinary’ social pressure can prove a powerful force in encouraging people to attend the polls (Campbell et al., 1960; Rosenstone and Hansen, 1993; Blais, 2000; Franklin, 2004).

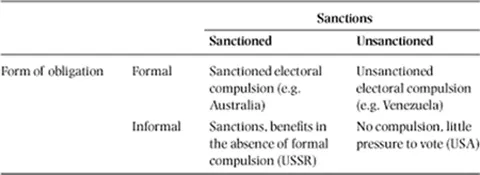

Table 1.1 A Typology of compulsory voting

In considering compulsory electoral participation, we are mainly interested in cases where electors have a legal obligation to attend the polls, but legal and informal socio-political forces interact in complex ways. The legal obligation to participate in elections can be congruent with social and political norms, or it can be at odds with one or both of these. There may also be considerable variations within a state – along geographical, sub-cultural, or other lines – in patterns of congruence. In schematic terms, we can understand there to be two types of obligation to vote: informal (social, political) and formal (legal). It should be noted that the enforcement of formal compulsory electoral participation requirements is often linked to a political and/or cultural environment that helps reinforce voting (i.e. congruence between legal and socio-political forces).

The interactions between these two dimensions of obligation yield a fourfold typology (see table 1.1). In the upper left-hand quadrant, we find the case of a formal obligation to vote combined with effective sanctions. The archetypal case of this is Australia where voting is compulsory, sanctions – though small – are effectively imposed, and there is considerable popular support for the institution. The upper right-hand quadrant represents a situation found in many Latin American countries, where compulsory electoral participation is a legal norm, but sanctions are either non-existent or are not applied. In the lower left-hand quadrant, we find cases where the formal obligation to vote is absent, but informal social and/or political pressures are so strong that a large proportion of the citizenry nevertheless exercise their franchise. The USSR was a good example of this type of system; on election day Communist Party activists would repeatedly knock on the doors of non-voters and urge them to the polls. Though there is little evidence that non-voting had nefarious consequences for Soviet citizens, there was a widespread perception that it might be harmful to one’s career or one’s chances of obtaining scarce goods (Mote, 1965: 76–83). There is a similar situation in contemporary North Korea; Mark Suh reports that ‘although voting is not compulsory by law, the political prescriptions laid down in the party catechism prescribe it as the correct behaviour of every citizen. A simple negligence, let alone denial [sic] to take part in the polls, would be followed by harsh discrimination in the living and working sphere of the person concerned’ (Suh, 2001: 399–400). Finally, in the lower right-hand quadrant, we find the situation in the vast majority of established democracies, but perhaps best represented by the United States, where voting is voluntary and there is little social pressure to vote.

It should be noted that the categories in this typology are not mutually exclusive, in as much as the formal obligation to vote is often reinforced by informal sanctions. Legal obligation and sanction may therefore be viewed as two overlapping but not coextensive spheres. On the one hand, there may be a legal obligation to vote in the absence of any formal sanction for non-voting. Such an obligation does potentially have importance, as it often represents a touch-stone in political debates, and it reflects an act of collective self-binding – it can therefore be seen as an indication of, and mechanism for perpetuating, a certain cultural attitude toward voting. On the other hand, a state can impose formal sanctions for non-participation in the absence of any formal requirement to vote. This is the case, for example, in Iran where ‘though voting is not compulsory, citizens may have to show the stamp impressed on voters’ identity cards in polling stations when applying for passports’ (Kauz et al., 2001: 64). Until recently, Italy provided a democratic example of this practice. Electoral participation is not obligatory, yet voting is described as a duty in the Italian constitution (Art. 48). This prescription was reflected in Italian electoral law between 1946 and 1992 (Caramani, 2000: 64f), when light sanctions were applied to non-voters (lists of non-voters were posted at polling stations).8 Another example is the US state of Illinois, which for a time put non-voters at the top of the list of those chosen for jury service, though voting was not technically compulsory (Abraham, 1955: 15–16).

Alternatively, the state can provide positive incentives for participation, either in the form of ‘vote facilitation’ mechanisms such as automatic registration, the availability of proxy voting, holding voting on a rest day, holding elections over more than one day, allowing absent and/or early voting, covering the travel expenses of voters who are temporarily away from their places of residence (see Franklin, 1996; 2002; Norris, 2004: 171–74), or by offering selective incentives to voters (see below).

Where voting is legally mandatory, a distinction is sometimes made between states that enforce the legal obligation to participate in elections strictly or weakly (e.g. Gratschew, 2004). The problem with this approach is that there are virtually no instances in the contemporary world of truly ‘strict’ enforcement. Commonly cited examples of ‘strictly’ enforced compulsory electoral participation are Belgium and Australia, but closer examination of these two cases reveals that in fact enforcement mechanisms take a light touch.

Stengers (1990: 105) writes that once compulsory electoral participation was introduced in Belgium it became a way of life, and compliance was due more to social norms than to actual sanctions, which were in any case only sparingly applied; he notes that ‘it is more a matter of habit than of obligation’9 (1990: 105). Belgians simply got used to voting and took it for granted that if an election were held, they would be expected to turn up at the polls. This view is confirmed by Pilet, who reports that in Belgium in 1985, only 62 of 450,000 non-voters were punished (Pilet, 2005: 20). Similarly, Lieven de Winter and colleagues point out that in 1999 the chances of being subject to a fine were only 1 in 10,000, and they note that ‘Given its scarcely civic behaviour in many domains, and given the tradition of impunity before the law, the massive electoral participation of Belgians ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of tables

- Preface

- 1 Introduction

- 2 A history of compulsory voting and an overview of contemporary experience

- 3 Normative arguments for and against compulsory voting

- 4 Compulsory voting and election campaigns

- 5 Compulsory voting and electoral turnout

- 6 Compulsory voting, electoral integrity and democratic legitimacy

- 7 Compulsory voting and political outcomes

- 8 Conclusion

- Appendix: sources of data and variable construction

- References

- Index