![]()

![]()

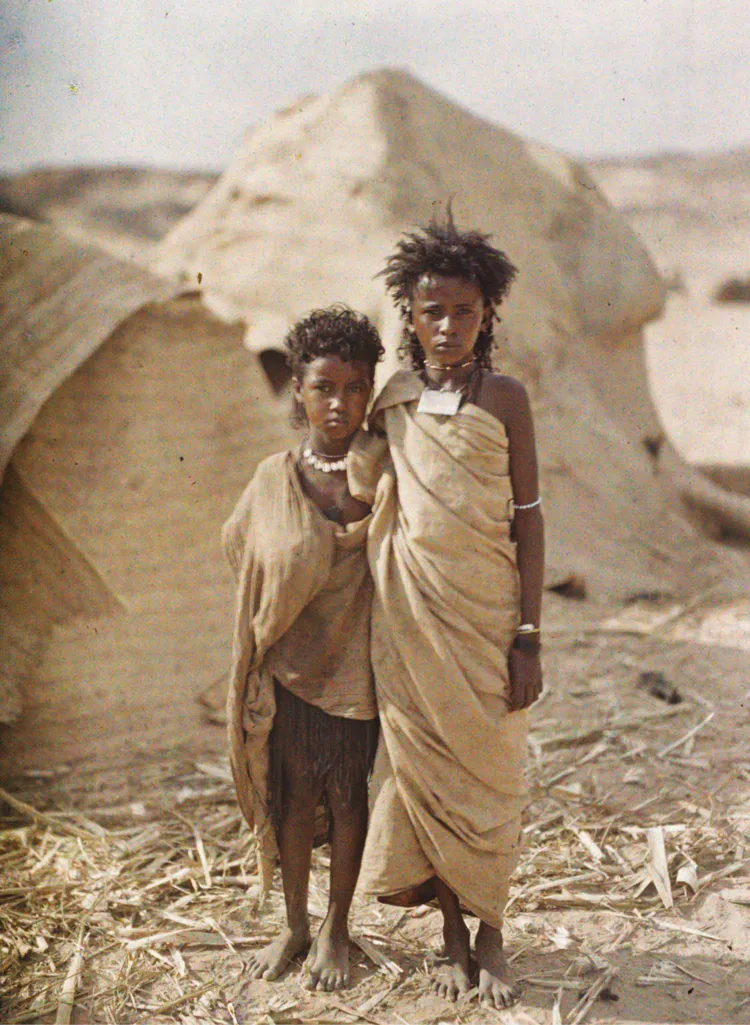

Rich banker, enlightened amateur and humanist artisan of a huge peace-making project, Albert Kahn invested most of his personal fortune in promoting progress of the social sciences and humanity, wanting to give human beings the means to know each other better.1 From this desire there remains a theme park of four hectares (ten acres) – a miniature world where different landscape sensibilities meet, as well as the collection of The Archives of the Planet, an inventory of cultural realities captured in nearly 72,000 autochromes and more than a hundred hours of films.

Within the relative homogeneity of the three media of The Archives of the Planet, autochromes, film and stereographs, a polysemic project plays itself out that exhibits the real heterogeneity of the treated subjects by crossing different types of stories, disciplines, influences, and relations with the Other. However, this project inscribes itself into the heart of a complex period of transition between two centuries with multiple references. It gives an account of a world that undergoes profound changes by simultaneously expanding and circumscribing itself; a world where parts that have only recently entered into contact and began to communicate mutually come to influence each other and to clash; a world where unprecedented technological progress makes possible the shortening of distances, the exploration of the infinitely large and the infinitely small and the mechanical recording of reality.

In this context, The Archives of the Planet originates from the encounter of two personalities and two visions respectively, sometimes parallel and sometimes competing, sometimes complementary and sometimes contradictory. Albert Kahn and Jean Brunhes, both men of conviction, each engaged in his own way, one moulded by parliamentarianism and cosmopolitan pacifism, the other by social Catholicism. The Archives of the Planet is shaped by these tensions. They make this program complex, difficult to understand and read, but they also turn it into an unequalled testimony of the upheavals of this period. It is at the very heart of these contradictions that we must look for the intrinsic coherence of this prolific work made of images that are conventional or unexpected, beautiful or banal, quickly forgotten or permanently inscribed in the collective imagination. The premise of this chapter is to question the purpose and the vocation of such a visual project: Do the images constitute an autonomous archive or do they have to be accompanied by a critical apparatus in order to make sense? Do they safeguard what will disappear, or do they testify to the reality of a changing world? Do the images address their contemporaries or future generations? Are the images positivist data or do they offer the means to act on reality?

Between Travelogue and Scientific Approach

Thanks to technical progress that facilitates travel, the nineteenth century pursues and amplifies the inventory of the world undertaken by the natural scientists of the time of the Enlightenment by expanding the initially nature-, fauna- and flora-centred fields of investigation towards an interest in populations and cultures. This movement is accelerated by the development of mechanical modes of recording reality.

The photographic image incarnates right from its beginning a form of representation able to capture this new perspective on humanity. Shortly after the process is made public in 1839, travellers, adventurers, officials, tradesmen, idealist scholars and missionaries bring the first images from regions and peoples hitherto unknown to Westerners. Disrupting the techniques of recording visual reality through drawing, photography is at first considered as a surface on which a directly capturable reality beyond any ideological or aesthetic choice is inscribed. The illusion is so perfect that the subjectivity or personal talent of each photographer is reduced to nothing. This belief endows the photographic and then cinematographic image with an irrefutable, anonymous, distanced and objective proof value. It is perceived to be an authentic archive that constitutes a flattened ‘reality’, easy to store and easily communicable and comparable.

These visual archiving projects are very generally based on a principle of collecting and classifying pre-existing images that are usually diverted from their original use. In contrast to this approach, the work done for Archives of the Planet first appears similar to the work of a production company. As Kahn states, in a letter to Brunhes, 26 September 1912, direct practice in the field by photographers and cinematographers is a key element of the project: ‘Field studies seems to be the only way to do real geography. They will take their full value and produce their full effect when our whole little planet has become familiar to you’.2 The experience of travel is central to Kahn. In 1898, after a journey in the Far East he conceives the first opus of his works: Scholarships should give young people an opportunity to discover the world other than via books; candidates should be interested in social, colonial and economic questions, in a gentlemanly fashion. Ten years after his first trip, Kahn undertakes a world tour mainly for business purposes. He is accompanied by his mechanic-chauffeur Albert Dutertre, whom he has initiated into photography. The banker envisions total representation and seeks to accumulate as many facets of reality as possible. To this end he invests in two stereoscopic cameras, a film camera and a wax cylinder phonograph. However, sound recording was deemed a failure in the end. It would no longer form a part of Archives of the Planet; other enterprises would take care of it.3 Nevertheless, thousands of images were taken by Dutertre. This trip can be seen as a preparatory mission. The images brought back correspond largely to those of a pleasure trip. The amateur photographer creates the material chronicle of the voyage (transportation, meetings and logistics). The many snapshots result in a corpus of picturesque everyday life scenes and views of remarkable monuments. This inaugural campaign, a veritable crucible for experimentation, remains closely linked to the banker’s personal activities and travels. The project then takes on scale and is organized and professionalized as technological choices are developed, camera operators are recruited and a scientific direction is established.

Although Dutertre succeeds in taking some autochromes during the journey round the world, Kahn actually discovers the potential of this process during the projections organized by Jules Gervais Courtellemont. Since November 1908 the photographer explorer has been offering his Visions of the Orient, lectures accompanied with images from his voyages. These photographs have nothing to do with a topographic survey but they result from compositions that sometimes lean towards the Orientalist genre scene. Some of them soon enrich the embryonic fund of The Archives of the Planet and thus confirm the ambiguity of the ‘scientific’ departure, far removed as they are from the supposedly objective recording of the real that is essential to any positivist approach. Still, the impact of these projections on the banker marks the actual starting point of the autochrome collection.

Auguste Léon, a trained master in the art of autochrome, is the first professional photographer recruited by Kahn in 1909. In the following years he accompanies the banker during the majority of his travels in France and abroad. Another meeting with a soon-to-be-retired ‘artillery warrant officer’ takes place a few months later. Able to handle the photographic and film cameras indiscriminately, Stéphane Passet comes across as an adventurer ready to take risks, in the tradition of the nineteenth-century scientific explorer. The operating chain then distinguished the collecting work provided by the traveller from the analysis produced by the ‘cabinet’ scientists. Field work did not require any particular university experience, but it required a solid constitution and a pronounced taste for adventure alongside a real technical know-how. In the tradition of the great explorers, Passet gives an important place to the story of his adventures, to the point where one sometimes wonders if his own journey is not the real subject of his missions.

In general, given the short duration of their stay and with the range of interlocutors generally limited to official representatives, the photographers’ virtual absence of scientific training severely limits their ability to understand the internal logic of the studied culture. Travelling alone, accompanied only by their tourist guides and exposed to chance meetings, it is difficult for them to escape the influence of conventional images when trying to depict the Other. Kahn is obviously aware of this problem and goes quickly in search of a scientific director, ‘an active man, young enough, accustomed both to travel and education, and with recognized skill as a geographer’.4 This providential man incarnates himself as Jean Brunhes.

Introducing a Scientific Approach

At the time when Kahn launches his visual inventory of rapid world changes, the relevance of images to the constitution of archives still remains to be demonstrated (the written document represents the only source of historical analysis considered reliable). However, in human geography, which is established as a discipline of the human sciences and has practical on-site experience as one of its essential methodological elements, photography is adopted to a previously unknown scientific extent. This very young discipline is interested in the dynamics between man and his environment, as well as in activities that enable the occupation and transformation of space. As such, it asserts itself as the science of the visible and gives the recording of concrete space...