- 566 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The story of the founding and growth of one of the nation's exceptional institutions for higher learning

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Trinity University by R. Douglas Brackenridge in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

TEHUACANA

It is thought that no more desirable location could have been selected than Tehuacana. It is proverbial for its healthfulness, supplied with an abundance of living water, surrounded with a beautifully romantic scenery and fertile country, capable of sustaining a dense population, central, and easy of access, being on the line of the Central Railroad and now with a short day’s ride of the Terminus, and free from the temptations to vice abounding in the various towns of the country.

Trinity University Catalogue, 1869–1870

CHAPTER ONE

A UNIVERSITY OF THE HIGHEST ORDER

Unanimously resolved that it is proper and expedient that steps be taken at once to locate and establish in the State of Texas, a University of the highest order, to be controlled by the Synods in said state.

SYNOD LOCATION COMMITTEE, 6 DECEMBER 1867

THE CREATION OF THE REPUBLIC OF TEXAS in 1836 marked the beginning of an era of colonization that dramatically changed the area’s social fabric. The expression “Gone to Texas” (or simply G.T.T.) chalked on the doors of houses in the southern states announced the departure of families to the frontier area. Despite lack of resources and conflict with Native Americans, immigrants responded to a generous land policy, and the population burgeoned. By the time Texas attained statehood a decade later, the Anglo population had grown from an estimated 34,470 to 102,961 and the slave population from 5,000 to 38,753. Growth accelerated further, and on the eve of the Civil War, Texas had a population of more than 600,000 residents.1

Among the new arrivals were significant numbers of Cumberland Presbyterians who immigrated from Tennessee, Kentucky, Virginia, Alabama, and other southern states. The Cumberland Presbyterian Church had its origin in the milieu of the early nineteenth-century frontier revivalism referred to by historians as the Second Great Awakening. While some members of the mainstream Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A (PCUSA) embraced revivalism as a valid means of church renewal, others criticized its emotional excesses and lack of decorum.

In dire need of clergy because of the rapid growth of church membership, the Cumberland Presbytery in Kentucky ordained ministerial candidates who lacked college degrees and formal theological training but who had been privately tutored by educated and experienced ministers. As a result, however, the Synod of Kentucky suspended the revivalist supporters for acting “contrary to the rules and discipline of the Presbyterian Church.” After efforts at reconciliation failed, the revivalist Presbyterians separated from the PCUSA and created an independent presbytery in 1810, marking the beginning of a new denomination.2

Characterized by spontaneity and mobility, Cumberland Presbyterians nevertheless valued both experiential religion and higher education. Although they espoused a religion of the heart that emphasized radical conversion and a personal relationship to Christ, they also respected education as a means of producing informed clergy and responsible citizens. To prepare individuals for life and for eternity, Cumberland Presbyterian educational institutions considered the Bible to be foundational to all learning and employed only faculty whose moral values and theological beliefs coincided with denominational perspectives.3

Call for Ministers

If your heart is drawn out by the love of souls, and if you want a field where your labors will tell to the next generation how, and for what purpose you have lived, then go to Texas. But note this fact—the Texans are, and will be, a race of high-minded, ardent, enterprising freemen of the genuine southern stamp—very different from the rude simple-hearted backwoodsman of the west; and therefore it is desirable that he who would minister to such a race in holy things should possess not only ardent piety and a meek Christ-like spirit, but such intellectual advantages as will enable him to grapple with minds of the first order.

The Cumberland Presbyterian, 25 March 1837

Despite a late entry into the field of higher education, the Cumberland Presbyterians founded and/or controlled about thirty-nine institutions identified as colleges or universities during the nineteenth century. Scattered from Pennsylvania to California, including ten in Texas, all but two of the twenty-two institutions established before the Civil War had failed by the end of the war. Between the end of the Civil War and the beginning of the new century, the Cumberland Presbyterians opened the doors of fifteen new schools. Among those that endured were Bethel College (Tennessee), Waynesburg College (Pennsylvania), Lincoln University (Illinois), Trinity University (Texas), and Missouri Valley College (Missouri).4

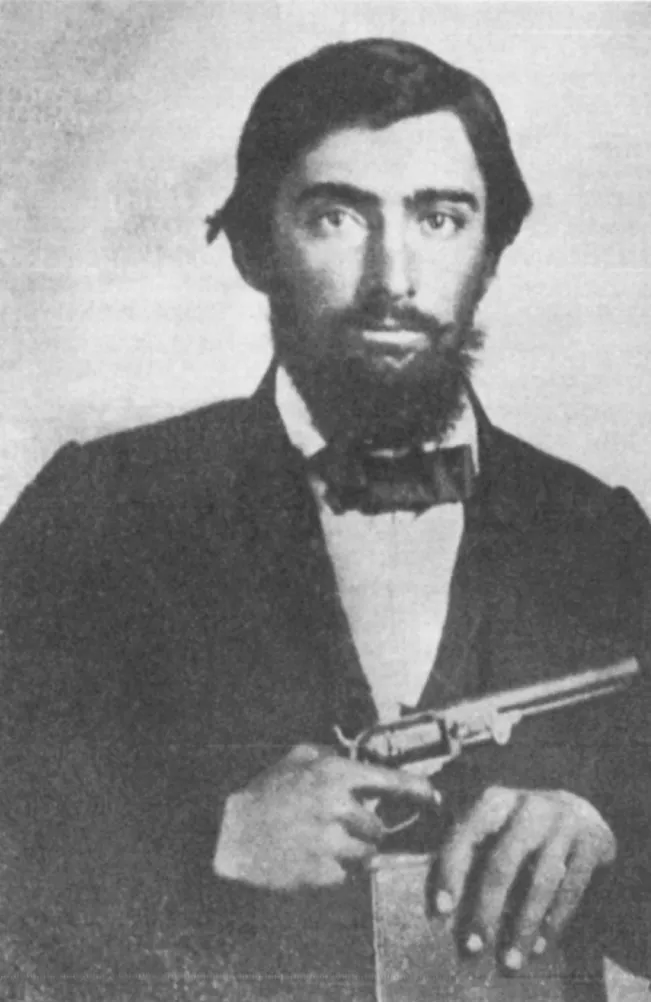

Sumner Bacon, “The Apostle of Texas”

Although lacking physical comforts, financial resources, and pastoral leadership, Cumberland Presbyterians adapted well to frontier conditions in Texas. Their evangelical piety and ecumenical spirit enabled the denomination to take root and outpace the growth of other Presbyterian bodies. As early as 1829, colorful Cumberland lay evangelist Sumner Bacon crossed the Sabine River into Texas and embarked on a missionary career that earned him the sobriquet “the Apostle of Texas.” Defying a Mexican law that permitted only Roman Catholicism, Bacon surreptitiously distributed Bibles and conducted revival meetings in fields. Forced to flee from Mexican troops on numerous occasions, Bacon found conditions more favorable when colonists banded together and drove the Mexican garrisons from Texas soil. After serving as a chaplain and courier for General Sam Houston during the war against Mexico and having secured ordination, Bacon organized one of the first Cumberland Presbyterian churches in Texas during the summer of 1836.5

Following Bacon’s example, pioneer Cumberland clergymen such as Samuel Corley, Andrew Jackson McGown, and Richard O. Watkins commenced evangelistic ministries in the Republic of Texas. Together they recruited members and organized small, rural congregations in east and central Texas. In 1837, Bacon and two other ordained ministers established the Texas Presbytery in a meeting held near San Augustine, Texas. Five years later, two additional presbyteries, Red River and Colorado, were created, and representatives of the three governing bodies met to form Texas Synod in 1843. Because of continuing immigration, Cumberland Presbyterianism experienced remarkable growth in Texas during the antebellum era. In 1840, only a single presbytery existed, with 10 churches, 200 communicants, and 6 ordained ministers. Ten years later, the denomination reported 2 synods (Texas and Brazos), 6 presbyteries, 83 congregations, 2,850 communicants, and 64 clergymen. Just prior to the Civil War, statistics reveal 3 synods (Texas, Brazos, and Colorado), 12 presbyteries, 155 congregations, 6,200 communicants, and 126 ministers.6

Despite their increasing numbers, most Cumberland Presbyterians lived in isolated rural settings that precluded the establishment of large congregations. Cumberland churches usually had communicant rolls of fewer than thirty members and often lacked adequate buildings or permanent pastors. Itinerant ministers depended almost solely on the generosity of people who were able to eke out only a meager existence in dryland farming. Milton Estill reported an annual salary of $145.25 in 1851, and William Travelstead of Red River Presbytery collected only $45.00 in 1854.7 Traveling more than a thousand miles in Stephens County, O. W. Carter held 200 religious services and revival meetings for which he received $75 in remuneration and a promise of $250 for the following year. Fortunately, few ministers reported, as did W. M. Speegle of Elgin, Texas, in 1883, that they “preached fourteen times at twelve different places and received one dollar and that too from a half-drunk man.”8

Nevertheless, Texas Cumberland Presbyterians initiated a number of educational endeavors prior to the Civil War that bore the name of academy, institute, or college. Most were little more than grammar or secondary schools with only a few collegiate-level students in attendance. At the first meeting of Texas Presbytery in 1837, Bacon and his compatriots resolved to establish at an early date “a seminary of learning” primarily for ministerial candidates. Reminiscent of other pioneer Presbyterian educational institutions, the proposed school was to combine “manual labor and literary pursuits.”9 Although the school never materialized, others provided formal education for future Cumberland leaders. In 1846, Red River Presbytery reported to Texas Synod that an academy at Clarksville was operating under its supervision. At the same time, the Texas and Colorado presbyteries were taking steps to enter the educational field in the near future. Other presbyteries instigated similar ventures, although, in many cases, the precise relationship between the school and the governing body is obscure.10

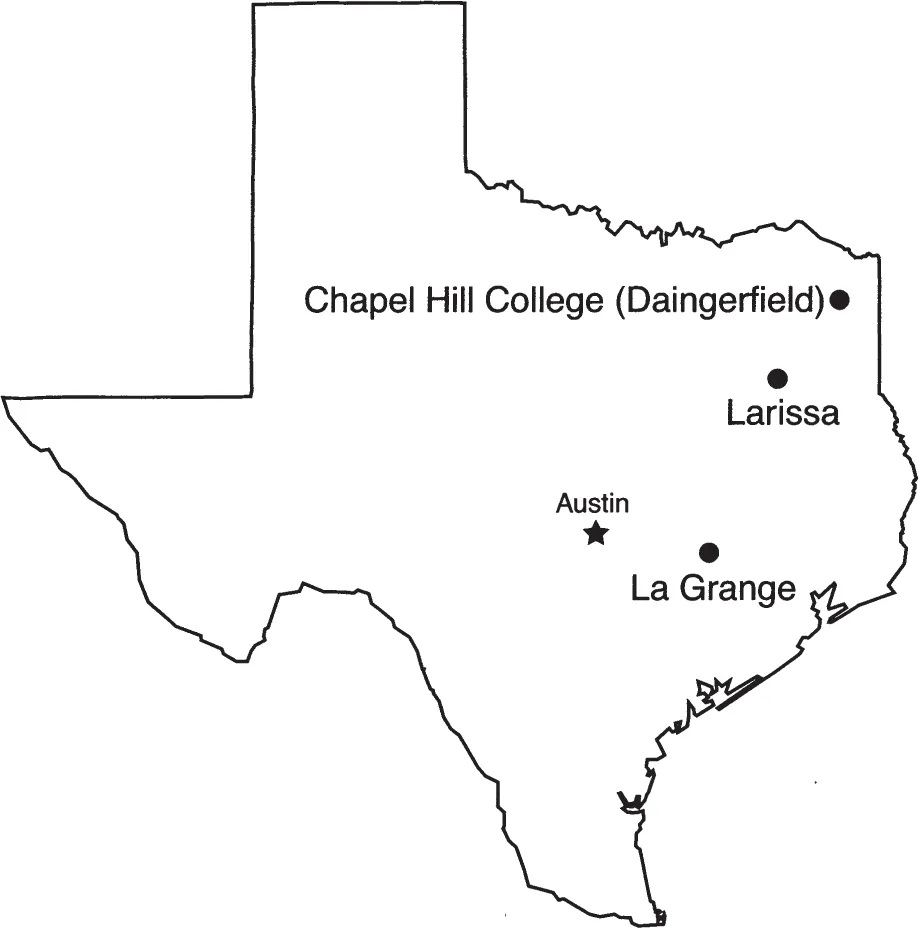

Map of the three college locations

Three schools that attained collegiate rank under the care of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church in Texas—Larissa College, La Grange Collegiate Institute (later Ewing College), and Chapel Hill College—are considered to be the forerunners of Trinity University. Although some sources refer to the “merger” of these three institutions to form Trinity University, in fact, there is no legal connection between Trinity and the three schools.11

All three institutions shared similar characteristics and met identical fates. Each was located in a rural village, free from what were deemed the negative influences of city life and in close proximity to a cluster of Cumberland Presbyterian settlers. Each school sought the formal endorsement of a governing body (synod or presbytery) and secured a charter that granted legal ownership and “general supervision” to its respective ecclesiastical body. “General supervision” consisted primarily of receiving an annual institutional report and approving charter amendments and trustee appointments. Otherwise, the schools retained considerable autonomy regarding internal operations such as faculty appointments, curricular decisions, and fiscal policies.12

Commencing operations with little or no endowment, the three colleges relied almost exclusively on tuition income to cover operating expenses. Consequently, any drop in enrollment imperiled institutional stability. Over time, gifts of land and cash from Cumberland supporters generated income for buildings and equipment but were insufficient to provide the endowment needed to acquire a strong faculty and to maintain and upgrade facilities. Like most other peer institutions in Texas, the three schools would never recover from the economic impact of the Civil War and Reconstruction and, after hostilities ceased, were unable to resume collegiate operations.

The origins of Larissa College date back to 1846 when a group of Cumberland Presbyterians from Tennessee led by Thomas N. McKee emigrated to Cherokee County, Texas. Eight miles northwest of what is now the town of Jacksonville, they established the village of Larissa. Utilizing a small log hut on the outskirts of the village, McKee’s sister, Sarah Rebecca Erwin, opened a school in 1848 under the auspices of Trinity Presbytery. The following year, Brazos Synod reported that the school was in a “permanent and flourishing condition” and urged congregations and individuals to give financial support to the new educational venture.13 In 1850, completion of a two-story frame building enabled the school, initially known as Larissa Academy, to attract students from surrounding towns and villages.14

The institution entered a new phase of educational activity in 1855 when it obtained a charter and incorporated as Larissa College under the ecclesiastical supervision of Brazos Synod. Although the synod granted administrative autonomy regarding faculty and curriculum, it retained the right to veto what it deemed “improper appointments” to the school’s board of trustees.15 Immediately following incorporation, Larissa College enjoyed a brief period of prosperity and gr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Part One: Tehuacana

- Part Two: Waxahachie

- Part Three: San Antonio

- Epilogue: Into a New Century

- Appendix

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index