![]()

1

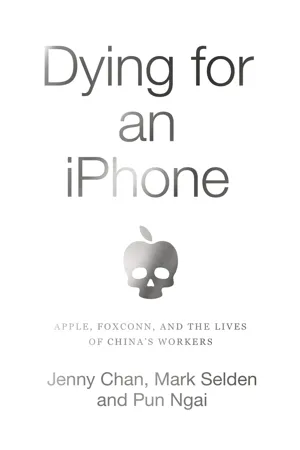

A Suicide Survivor

I was so desperate that my mind went blank.

—Tian Yu, a 17-year-old suicide survivor1

At about eight in the morning on March 17, 2010, Tian Yu threw herself from the fourth floor of a Foxconn factory dormitory. Just a little over a month earlier, she had come to Shenzhen city, the fast-rising megalopolis adjacent to Hong Kong that has become the cutting edge of development in China’s electronics industry. While still a predominantly rural area when it was designated as China’s first Special Economic Zone in 1980, Shenzhen experienced extraordinary economic and population growth in the following decades to become a major metropolis with a population exceeding 10 million by 2010, with nearly 8 million internal migrants from within Guangdong and other provices (who were also known as the “floating” population).2

Yu, who hailed from a farming village in the central province of Hubei, landed a job at Foxconn in Shenzhen. At the moment that she attempted to take her life, global consumers were impatiently waiting for the revamped iPhone 4 and the first-generation iPad. Working on an Apple product line of Foxconn’s integrated Digital Product Business Group (iDPBG), Yu was responsible for spot inspections of glass screens to see whether they were scratched. An ever-shorter production cycle, accelerated finishing time, and heavy overtime requirements placed intense pressures on Yu and her coworkers.

Miraculously, Yu survived the fall, but suffered three spinal fractures and four hip fractures. She was left paralyzed from the waist down. Her job at the factory, her first, will probably be her last.

Tian Yu, half-paralyzed after jumping from the Foxconn Longhua factory dormitory, received treatment in the Shenzhen Longhua People’s Hospital in Guangdong province.

Surviving Foxconn

Our first meeting with Yu took place in July 2010 at the Shenzhen Longhua People’s Hospital, where she was recovering from the injuries sustained in her suicide attempt. Aware of her fragile physical and psychological state, the researchers were fearful that their presence might cause Yu and her family further pain. However, both Yu’s parents at her bedside, and Yu herself when she awoke, put them at ease by welcoming their presence.

Over the following weeks, as Yu established bonds of trust with the researchers, she talked about her family background, the circumstances that led to her employment at Foxconn, and her experiences working on the assembly line and living in the factory dormitory. During interviews with Yu and her family, it became clear that her story had much in common with that of many Foxconn employees, comprised predominantly of the new generation of Chinese rural migrant workers.

“I was born into a farming family in February 1993 in a village,” Yu related. What was recently a village is now part of Laohekou (Old River Mouth) city, which has a population of 530,000. Located on the Han River close to the Henan provincial border, it was liberated in the course of the anti-Japanese resistance of the 1940s. Following a redistributive land reform, in the mid-1950s, agricultural production was organized along collective lines. During the late 1970s, with the establishment of a household responsibility system in agriculture, followed in 1982 by the dismantling of the people’s communes, farmland was contracted to individual households.

“At best my family could earn about 15,000 yuan on the land in a year, hardly enough to sustain six people. Growing corn and wheat on tiny parcels of land and keeping a few pigs and chickens might not leave us hungry,” Yu said, “but making a better life is challenging if one seeks to eke out a living on the small family plot.”

Yu belonged to the generation of “left-behind children” as both parents joined the early out-migration wave that enveloped China’s countryside. Yu’s grandmother brought her up while her parents were far from home supporting the family as migrant factory workers. Like many of the 61 million children who were left behind, she spent her early childhood playing with other neighborhood children.3 There was little parental guidance. Eventually, her parents returned home to resume farming having earned just enough money to renovate the house. Yu, the eldest child, has a sister and a brother. She hoped, in the future, to be able to help look after her brother, who was born deaf.4

From Farm to Factory

China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001 brought about great challenges to villagers, who faced a flood of cheap subsidized crops imported from overseas even as export-driven industrialization expanded. Despite gains associated with the elimination of agricultural taxes in 2005 and the subsequent establishment of a social insurance scheme under the new socialist countryside campaign, as most young people departed for the cities and industrial jobs, the prospects for household-based agriculture and rural development generally darkened. Sporadic efforts toward cooperative rural construction and alternative development initiatives aside, opportunities for sustainable farming and lucrative nonfarm work in remote villages remained scarce.

After graduating from junior secondary school and completing a short course at the local vocational school, Yu decided to leave home to find a job. For her cohort of rural youth, the future, the only hope, lay in the cities. By 2010, TV and especially internet technology and mobile communications had opened a window on the real and imagined city lifestyle. “Almost all the young people of my age had gone off to work, and I was excited to see the world outside, too,” Yu explained.

Soon after the Spring Festival, the Chinese New Year, in early February 2010, Yu’s father gave her 500 yuan to tide her over while searching for work. He also provided a secondhand cell phone so that she could call home. He asked her to stay safe.

In the morning, “my cousin brought me to the long-distance bus station,” Yu recalled of her departure for the city. “For the first time in my life I was far away from home. Getting off the bus, my first impression of the industrial town was that Shenzhen was nothing like what I had seen on TV.”

On February 8, at the company recruitment center, “I queued up for the whole morning, filled out the job application form, pressed my fingertips onto the electronic reader, scanned my identity card, and took a blood test to complete the health check procedures.” Yu was offered a job and assigned a staff number: F9347140. She also received a color-printed Foxconn Employee Handbook, which was replete with upbeat language for new workers: “Hurry toward your finest dreams, pursue a magnificent life. At Foxconn, you can expand your knowledge and accumulate experience. Your dreams extend from here until tomorrow.”

Later, after a quick lunch, a human resources manager at an employee orientation told a group of new recruits, including Yu, “Your potential is only limited by your aspirations! There’s no choosing your birth, but here you will reach your destiny. Here you need only dream, and you will soar!”

The manager told stories of entrepreneurs like Apple chief Steve Jobs, Intel chairman Andrew Grove, and Microso...