1

Infant and Child Health in the United States and France

All grown-ups were once children … but only a few of them remember it.

—Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince

Paris, France. I am standing at the reception of the École Maternelle André del Sarte, a bustling preschool located in the city’s immigrant-rich eighteenth arrondissement (district), trying to enroll my three-year old daughter. There is no language barrier. I speak fluent French. Nor is money an issue. High quality preschool is free and open to all comers in France. But there is a matter of health. A bespectacled middle-aged secretary patiently informs me that my daughter “cannot be enrolled without a carnet de santé, a record of her vaccinations and health history.” “No problem,” I say to myself, as I hand over her multilingual World Health Organization prophylaxis certificate with all her vaccinations dutifully recorded, stamped, and signed by various clinics. The secretary takes only a quick glance at the document before saying, “Unfortunately, sir, this is unacceptable.” I have lived in France long enough to know that failure to produce exactly the right document makes protest futile. “Where might I obtain the required carnet de santé?” I ask. “Your family physician or any Protection maternelle et infantile [PMI] clinic,” she answers.

Little did I know then that “la PMI” would soon become a familiar term in our household. We also had one-year boy who needed a spot at one of the city’s crèches (infant care centers). He too would need a carnet de santé. The PMI clinic on Rue Carpeaux soon became our regular doctor’s office where the children always saw, by appointment and without charge, the same pediatrician who also had a private practice elsewhere in the city. Not only did our children need their WHO records transferred to a carnet de santé; they needed tuberculosis vaccinations (not just TB tests) that are not commonly administered in the United States, well-child visits, and occasional curative care. The PMI provides free preventive and primary care services to women up to age fifty and any child under six years of age, no questions asked, and its precepts are fully integrated into the nation’s maternity leave programs, infant and childcare services, and preschools. In France, women and children are guaranteed access to the PMI because they are women and children. Comparable efforts in the United States rely on a jumble of federally assisted state efforts, primarily Medicaid, the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Eligibility for all of them is tied to poverty assistance; therefore a child’s access to care can fluctuate from one month to the next according to family income. Moreover, US children’s health efforts are poorly integrated, if at all, with maternity leave programs, the federal Family and Medical Leave Act, childcare centers, and preschools, all of which are vital social determinants of child wellness.

In contrast, the French maternal and child health programs, although not without their problems, at least function as a coordinated whole. How did such a comprehensive system to protect maternal and child health come about in France? And what explains the divergence, which began in the early 1900s, between the US and French efforts to protect infant and child health? This chapter traces the historical development of the institutions that affect children’s health in France. These include the early regulation of infant care and milk processing; the building of infant care centers and public preschools; the establishment of universal access to maternal, well-woman, and pediatric care; and the implementation of paid parental leave. Alongside the French story, I examine comparable US initiatives, which more often than not were vanquished by powerful entrenched interests or ran aground on the shoals of political inertia. The US initiatives included state pensions to low-income mothers so they could remain at home with their young children; universal access to children’s health services; and subsidies for women to obtain obstetrical and perinatal care.

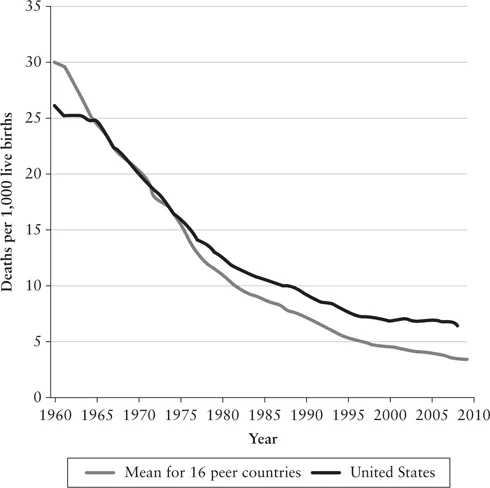

The United Nations considers the infant mortality rate as the “measure of all things” because it is “directly affected by the income and education of parents, the prevalence of malnutrition and disease, the availability of clean water and safe sanitation, the efficacy of health services, and the health and status of women.”1 The infant mortality rate is defined as the annual number of infants per 1,000 live births who die during their first year of life. An Institute of Medicine study that compared the United States with sixteen peer-income nations, including France, found that American infants and children, from birth to age four, are most likely to die or suffer from life-threatening conditions. The United States ranked last in infant mortality (5.8 per 1,000), last in neonatal mortality (4.4 per 1,000), last in low birth weight (8.2 per 1,000) and thirteenth in perinatal mortality (6.6 per 1,000).2 The US child relative income poverty rate (20.9 percent) is much higher than that of similar-income nations (13.1 percent) and nearly double that of French children (11.5 percent).3 US adolescents are also more prone to experience obesity, HIV infection, injury, assault from firearms, and pregnancy. American pregnant and postnatal women are in similar straits. Unlike that of any other wealthy nation, US maternal mortality has been rising for the past fifteen years, and it now stands at 26.4 per 100,000 births; in France the rate has been falling and now stands at 7.8 per 100,000.4 Had the United States achieved just the average childhood mortality rate of comparable-income nations, 600,000 lives could have been saved between 1961 and 2010.5

Like the United States, France is a socially, ethnically, and racially diverse nation with high rates of in-migration from its former colonies in North Africa and Asia. In 2015, 12.1 percent of the French population and 14.5 percent of the US population were made up of international migrant stock. Yet France’s average infant mortality rate (3.8 per 1,000) is below the rate of one of the most advantaged US population subgroups: non-Hispanic white women (5.6 per 1,000).6 Educational attainment, an important marker of socioeconomic status, also fails to explain the relatively poor US performance. Infants of college-educated American mothers with sixteen or more years of education are more likely to die before their first birthday (4.2 per 1,000) than an infant from an average French mother (3.8 per 1,000).7

For much of the last century and a half, France and the United States successfully reduced their infant mortality rates, despite the world wars of 1914–18 and 1939–45 and the Great Depression of the 1930s. Indeed, in no small measure, the absence of war on the US homeland contributed to Americans’ ability to outdistance their French allies in the battle to improve infant survival and child wellness during the first half of the twentieth century. However, by the early 1960s the US advantage in infant mortality rates and child health outcomes had evaporated. Then, beginning in the 1970s, quite to the surprise of American health experts, other wealthy nations, including France, surpassed the United States. The Americans have since fallen further behind with each passing year.8

Figure 4. Infant mortality: United States vs. sixteen peer OECD nations, 1960 to 2009.

Source: National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, U.S. Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health, ed. Steven H. Woolf and Laudan Aron (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2013), 68.

This chapter identifies three historical developments that together explain why the French health system became more effective than the US health system at protecting infant and child health. First, the federal structure of the US government under which states could ignore or block national initiatives impeded child health efforts until the mid-twentieth century. Prior to the 1930s, the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Constitution restricted federal government actions on health and welfare matters, reserving those for the states. In contrast, the French Republic possesses a unified national government whose sovereignty over social policy matters is wide-ranging. Second, US private-practice physicians highhandedly mistook the power of their profession for an effective health system and blocked all government efforts to create universal access to health care services, including those specifically focused on children. French doctors also opposed state intervention into health care but ultimately struck a grand bargain with legislators that permitted the establishment of universal health care while protecting fee-for-service medicine and physicians’ professional sovereignty. Third, the United States deployed means-tested social and health care services, which, when joined with the heavy reliance on employer-based health coverage, created a tragic (and absurd) dichotomy between “deserving” and “less deserving” children. France reserved some of its social services for low-income families, but most maternal, infant, and child health programs are universally available to all comers.

The State, Race, and Class

The federal structure of the US government prevented laws passed in Washington, DC, from being imposed on the states until the 1930s, hindering US progress on infant and child health. Cities often stepped into the breach, implementing bold initiatives on behalf of their youngest residents. In contrast, France has long possessed a unified national government. Its regional administrative units, the départements and régions, although important in some matters, possess neither the political authority nor funding resources of US states. The national government based in Paris could move quickly, imposing its will on even the most recalcitrant regional political leaders. Its most important early success took the form of 1874 Roussel Law.

In the 1870s, a French country doctor, Théophile Roussel, who had been elected to the National Assembly, exposed the living conditions of newborns under the care of wet nurses. France’s industrial centers were woefully short of childcare options, especially for infants. Eventually, there arose a private unregulated wet-nursing and childcare industry that annually accepted some ninety thousand infants and children. Nearly 10 percent of French children ages zero to five lived with wet nurses, and in Paris, half of all newborns were so cared for. To be sure, many wet nurses provided their charges with adequate, even excellent attention. But Roussel exposed others who proffered fatally dangerous environments, especially for newborns. Shortages of breast milk meant the substitution of adulterated and unsanitary cow’s milk; too often the homes lacked sufficient heat; and the ignorance or willful disregard of hygienic practices surrounding defecation and bathing made infection common. Roussel railed against the plight of the suffering children, whom he called “this human capital that is so easily destroyed.”9 France’s Academy of Medicine had also been studying the wet-nursing industry and endorsed Roussel’s bill, assuring its passage. The new law required public health inspections of all facilities that accepted children of less than two years of age for wet-nursing or care in return for compensation. It also obligated wet nurses to demonstrate that their own children under seven months old were receiving proper care.10

The 1874 Roussel Law contributed to a decline in infant mortality by 1915. Equally important, it institutionalized the nation’s commitment to the improvement of infant and child health through the creation of a national health infrastructure. The government divided the country into public health districts; it developed standards of sanitation and methods for their measurement; and it hired hundreds of medical inspectors, drawn from local physicians who were engaged on a part-time, fee-for-service basis. The Roussel Law thereby created an expertise in public health administration that could facilitate subsequent health initiatives.11

Meanwhile, the United States took a different path that at first appeared promising. Health advocates, led by the New York surgeon Stephen Smith, founded the American Public Health Association (APHA) in 1872. Soon thereafter the APHA conducted a national survey of cities and towns greater than five thousand inhabitants in order to document local health conditions. In their responses, city officials commonly complained about courts’ reluctance to enforce health laws, “lest they seem to abridge the rights of property and individual freedom.”12 Determined to empower local health efforts, APHA leaders appealed to Congress and to President Rutherford B. Hayes to create a national board of health. The APHA’s lobbying effort succeeded in 1879, aided by the coincidence of a deadly yellow fever epidemic in the Mississippi Valley. However, Congress funded only seven physicians to cover the entire nation. Undeterred, the new National Board of Health forged ahead. Its first project was to create national quarantine standards to contain outbreaks of infectious disease. Immediately, several powerful state politicians objected. They refused to recognize any federal government authority on health matters and demanded the termination of the board. In 1883, Congress complied.13 Not until 1912 did the United States again create a national health authority, the US Public Health Service (USPHS). Even then, the powers of the USPHS to coordinate state health laws, let alone enforce national measures, paled compared to France’s Ministry of Health. When the US Public Health Service finally succeeded at overseeing infant and child health measures, it relegated immigrants and nonwhites to lower standards rather than ensuring broad-based efforts for all children.

Indeed, social Darwinism and eugenics colored US child health efforts from the beginning. The National Eugenics Society, led by Yale economist Irving Fisher, insisted that public health officials needed to first preserve what he called the “vitality of the national stock,” by which he meant northern and western European white Americans.14 Early US public health officials established the practice of analyzing infant mortality by race and ethnicity, ignoring socioeconomic class, and focusing most of their attention on recent immigrants. This opened the way to nativist, pseudoscientific, racist interpretations that ascribed infant mortality differentials between whites and nonwhites to biological determinism about which public health agents believed nothing could be done. Indeed, the president of the American Statistical Association, Frederick L. Hoffman, denounced those who attributed poor health and infant deaths to environmental or social conditions, saying, “It is not in the conditions of life but in the race traits and tendencies that we find the causes of excess mortality.”15 The ability to appreciate the effects of racial and ethnic discrimination is vitally important in a pluralistic society.16 However, the absence of analysis according to socioeconomic class hindered a comprehensive understanding of the social determinants of infant mortality. If US health officials had studied poor people, regardless of race or ethnicity, the full mix of factors that cause infant death and children’s ill health would have become apparent sooner.

France was hardly a utopia in this regard. Man...