![]()

1

BRITAIN’S FORGOTTEN

WOMEN SEAFARERS

Challenging huge Japanese whalers, Susi Newborn’s brief time life at sea was sometimes as exciting as that of women pirates 250 years earlier. For mobile women, wanting to explore their own selves as well as the world, seafaring can be the ultimate in adventuring and acting with agency. In the 1970s this Greenpeace activist described herself as leaping accurately – glad of her T’ai Chi training – into one of the Rainbow Warrior’s tiny fast Zodiacs (rigid inflatable boats) ‘as it thrashes and jerks like a rodeo yearling’. Barefoot and braced for bullets, she sailed at her targets in the name of peace and protecting the environment.

Green Campaigner Afloat

Susi Newborn (b. 1950s) became a founding director of Greenpeace and crewed on Greenpeace’s iconic campaigning vessel Rainbow Warrior in the 1970s and early 1980s. She is from an Argentinean diplomatic family but was born in London. Like most people on board Greenpeace ships, she had many roles, from Zodiac crew to deckhand to cook. Today she is a filmmaker and the campaigns co-ordinator for Oxfam New Zealand. She is still on the water every day, taking the Fullers’ ferry Quick Cat (many of whose crew are women) from Waiheke Island, where she now lives.1

Susi Newborn on the Rainbow Warrior in 1978 during the campaign against Icelandic whaling. (David McTaggart, courtesy of Greenpeace, GP026C6)

Susi loved the challenge, and her daring was rather akin to that of the world’s most famous women pirates, Anne Bonney and Mary Read, who swashbuckled in the Spanish Main in the eighteenth century. Their sailing era ended in 1720, thirty years before the period covered by this book, but such female boucaniers whetted the appetite of potential seafaring women and influenced common ideas today of ‘lady tars’ on all the world’s seas. (‘Tar’ is short for tarpaulin, the bitumen-covered cloth garments that seafarers – so-called ‘knights of the tarpaulin’ – used to wear to repel water.)

Archetypal Pirates of the Past

Cork-born Anne Bonney (1698–1782) is probably the most famous woman pirate, and always linked to her cross-dressed counterpart, Londoner Mary Read (1691–1721). Now archetypal ‘piratesses’, these two adventure-seeking footloose women sailed on the pirate sloop Revenge in the 1710s. Anne was Captain Jack Rackham’s lover, later his wife. By contrast, Mary (whom she heterosexually fancied) was passing as a male crewmember. Both were able to succeed in this seafaring lifestyle because in their childhood relatives had disguised them as boys, as a way to make enough money to live on. This meant that they grew up bold and relatively unconstrained by ideas of normality. Anne gained her chance to sail because she was enterprising (ready for a new life, free of a feckless husband), in the right place at the right time (Nassau waterfront bars where buccaneers recruited) and attractive to a captain who had the power to keep a partner on board. Mary gained her opportunities because she was already skilled at passing as a soldier.2 Their stories reached the public through popular potted, excitingly written biographies, especially Captain Johnson’s General History of the Pyrates. It’s hard to disentangle myth and fact; they may have sailed for several years. Their careers ended when they were arrested and brought to trial. They escaped hanging by swearing they were pregnant (an unborn child could not be punished for the sins of its mother).3

Susi Newborn of Greenpeace, too, was outside the law. And she learned firsthand about opportunistic sea tactics, violent enemy ships, storms, long-haired, hoop-earringed shipmates – and tedium. The reason she, a woman without seafaring skills and without that crucial seafarer’s passport, the British Seaman’s Discharge Book, could even be on board was that she was effectively one of the owners. As a volunteer on a small ship, she could freewheel between tasks. She even did the dirty work of cleaning bilges; as the smallest person aboard, she could fit into the narrowest spaces.

Susi was unusual, like Anne and Mary. Almost all the thousands of British women working at sea since 1750 were essentially domestic employees. Like my Great-Aunty May going to and fro, to and fro, between Liverpool and West Africa, these stewardesses travelled regular routes, making passengers’ beds as routinely as any chambermaid might. Their floating hotels initially seemed more exciting, and were certainly more challenging socially and geographically, than below-stairs life in a hotel or grand house. They had few choices and no stashes of Spanish doubloons.

‘Yes, I’m a woman.’ 1720s Pirate Mary Read reveals herself to a vanquished enemy. (Image from P. Christian, Historie des Pirates et Corsaires’, 1852, engraving by A. Catel from a sketch by Alexandre Debelle)

But many elements of Susi’s experience were typical of those early women’s sea lives too. They saw the world. They seized opportunities. They defied restrictive views of a woman’s place. And they survived months on the Atlantic, Pacific, South China Seas and beyond, with male crewmembers who thought a ship no place for a lady. Unlike Anne or Mary, these women were ‘out’ as women, meaning they were visibly female (which brought them into contact with the ship’s gendered hierarchy). Ironically, they gained their freedom to rove because of the limited and confining contemporary idea that lady passengers must be waited upon by females, oceangoing maids.

Two other categories of women sailed too. There were those who got opportunities because they were relatives of the master (as captains are called). An accommodating husband who wanted a travelling wife, and had the authority to take her with him, was a ticket to ride. US wives in the nineteenth century seemed to travel far more readily their British counterparts.

A further category includes women like Anne Jane Thornton, who disguised themselves as men and did men’s jobs. They belonged to the world of the vessel, the technical machine, rather than the neat bedroom. It was only in the second half of the twentieth century that it was possible to really combine being an out woman (meaning not pretending to be a man) and sailing before the mast,4 as a deck officer or engineer undisguised.

As of the 2010s, the UK’s 3,000 Merchant Navy women were 13 per cent of the total 22,830 UK seagoing workforce. Worldwide, women made up a smaller proportion, about 2 per cent of the total maritime labour force. Seawomen in the early twenty-first century are mainly on cruise ships, in hotel-type jobs. In the UK’s case, about two thirds of all its women seafarers are on such ships, not cargo vessels.5 Women are still mainly found doing these lowly paid ‘chambermaiding’ jobs on ships.

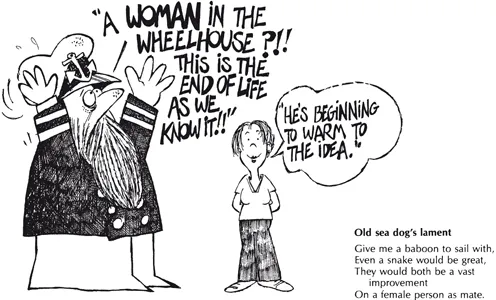

‘The end of life as we know it.’ Jim Haynes illustrates the typical reactions that faced a woman, Sally Fodie, when she first ventured on the bridge of a ship. (Captain Sally Fodie, Waitemata Ferry Tales, Ferry Boat Publishers, Auckland, 1995)

WIFE, ‘BOY’, ‘MAID’ AND EQUAL HUMAN BEING

These women seafarers were working far from home, in a field marked ‘men only’, or even ‘ruggedly masculine men only’. Yet they managed to break through into operating the vessel and taking the decisions at the very top, rising from the lowly domestic servicing of the ship’s hotel operations. It is a complex story, but the first women who went to sea for a living did so in the following three ways.

Sea Wives

First were the women who were ‘out’ as women: the seagoing wives of officers. The ‘plucky’ wife of Martinique-bound Warrant Officer William Richardson was one. William went to say goodbye to her one summer in the 1780s but ‘found that she had fixed her mind to go with me, as it was reported the voyage would be short and the ship would return … [However] in parting from her parents [she] almost fainted … but was still determined to go with me.’6 In the King’s (Royal) Navy wives sailed the oceans, including into battle. They did support work in crises from Africa to China, from the Baltic to the Mediterranean, from the East Indies to Central America. Invaluable auxiliaries and undervalued support workers, they were a bit like the sutlers and vivandières (sometimes called ‘camp followers’) who looked after armies on the battlefields of France and in the US Civil War by selling services and goods including hot food and nurture such as laundering. The Navy expected husbands to share food with wives; it didn’t victual or pay them (except for some rare pensions). Naval men sometimes struggled to control this group, which wasn’t organised under the same naval disciplinary codes. Horatio Nelson, England’s inspirational naval leader, said that women on ship ‘always will do as they please. Orders are not for them – at least I never yet knew one who obeyed.’7

Whaling wife Eliza Underwood was one of at most a thousand British wives on merchant ships, in the period from 1750 to roughly 1900, whose ships were sometimes called ‘hen frigates’ (interestingly, implying that the rest were cocks; today all-male RN ships are called stag ships). US and Antipodean wives avidly sailed. It’s their accounts, popularised by New Zealand historian Joan Druett,8 that today help us imagine the far less recorded situation of British wives. We certainly know wives had borrowed status, and they often took their offspring with them: ‘The captain and his wife and children were members of the royal family of a tiny but very wealthy, kingdom,’ explains historian Linda Grant De Pauw.9 Some spouses wanted each other’s company regularly, despite the privations. Cosying up in the best space on ship was cheaper than maintaining an additional home on land. Historians of whaling wives argue that when these women sailed they were not necessarily choosing a ‘feminist’ or ‘boyish’ adventure. Rather it was often a case of ‘whither thou goest I will go’, dutifully and no matter what the hardship.

Married to the Captain

Eliza Underwood (b. 1794, probably at Lewes, in Sussex) got her opportunity to sail because she married Samuel, who was already master of the London whaleship Kingsdown when they met. She had no children to tie her to home, and at that period captains’ wives were increasingly sailing on whalers (at least in the US). By 1829–31 Eliza was sailing to the Sulu-Sulawesi Seas whaling grounds and visiting many islands in Indonesia. Her journal reveals her isolation, tolerance (of the seamen’s limited domestic skills, for example: ‘they would make sad charwomen’) and remarkable tenderness towards her irate, seemingly mentally ill, husband. Tales of encounters with Muslims and exotic ports mingle with domestic rumblings: ‘He does not much attend to woman’s knowledge,’ she remarked, but she didn’t crow when her weather predictions proved better than his, yet again. And she was always concerned about his gout. She enjoyed collecting – and assessing the value of – rare shells, which she would later sell on in London.10

On very small ships wives got their chance to sail because they were useful. As auxiliary cooks and mates they supported the family business, when and how they could, particularly with informal nursing, laundering and bookkeeping. Unwaged and undervalued, their situation was similar to that of wives in family-owned corner shops who were incorporated into ‘his work’ for ‘our survival’. Often they were seen only as assistants, or utilisable in crises, but in fact some were consistently doing non-peripheral tasks and sustained the entire family’s economy.

Situations varied, especially by the late nineteenth century. But certainly on larger merchant ships of the mid-nineteenth century captains’ wives offered emotional support to their stressed and socially isolated husbands. They negotiated a tricky path vis-à-vis agency (meaning their ability to act, to engage with the ship’s social structure). Orcadia...