![]()

Emily as a Child

and a Young Woman

WHAT SHAPED THE character of the young Emily? Her parents and her closest family were obviously the strongest influence, but perhaps her school companions played a part. Finding anything from her younger days was, I thought, going to be difficult. However, I was then presented, out of the blue, with some rare documents from Longhorsley. These had been saved from Margaret Davison’s garden bonfire in 1918 by one of her neighbours. Mr and Mrs Jeffrey, of Morpeth, rang me to say that their parents and grandparents had owned the Leg of Mutton public house in Longhorsley at the time that Margaret Davison lived across the road. Could they call and see me to show me something that had belonged to the Davison family? Their name, and the location of Longhorsley, was significant. The census returns of Longhorsley listed the Jeffreys as the local publicans, living opposite Emily’s mother’s corner shop. We sat in my garden potting shed, drinking cups of tea, while they explained their unique relationship to the Davisons and the Caisleys. Mr Derek Jeffrey explained that his father, as a young boy, had been Margaret Davison’s handy man-cum-gardener. His wife, Eileen, was descended from Margaret Davison’s youngest sister Jane Caisley, who was born in 1853 in Morpeth and who had married John Waldie. According to the Jeffrey’s family story, the young gardener had realised that Mrs Davison was not at all well shortly before she died in 1918 – in fact, she seemed to be quite upset. One day, when the garden bonfire was ablaze, Mrs Davison came out of her house with lots of papers and asked the young boy to burn everything for her. He could see that some of them were private papers and books, one a scripture book and a birthday book. Being a young lad who had been taught to respect such things, he could not bring himself to do it. Instead, he took them over the road to his parents’ house to ask their opinion. One of the items was young Emily’s birthday book. In it she wrote down the birthdays of, and names of, her family and friends. I carefully transcribed the names and thanked Mr and Mrs Jeffrey for their kind help with my project.

The first list of names obviously records family names:

Robert E. Davison (her brother, born in Laurencekirk, Kincardineshire)

Amy S. Davison (her sister, born in Warblington, Hampshire)

William Davison, 1838 (unknown)

William S. Davison (her brother, born in Warblington)

The remaining names were probably her friends’ names. They are:

Bertha Clark; Annis Dawe; Edith M.J. Lloyd, 1872; H. Christiana Severn; Nellie Cummings, 1874; Dorothy Giles; Emily P. Story; Daisy Nicholson, 1872; Katherine Scott; S.M. Taylor; Lillie T. Cameron (may be an ‘S’ or a ‘T’ for the initial); Arthur S. John Carter; A. Baxter (or Barter) White; Agnes M. Hitchcock.

Who were they, these people whom Emily had carefully entered in her special book?

Professors Carolyn and David Collette from Massachusetts now enter the story: they were in Morpeth’s library one day, asking for any information the librarian had regarding Emily Wilding Davison. The librarian rang me immediately. I invited them to come up to my home, and that was the beginning of a wonderful friendship. Carolyn’s field of expertise is medievalism and the works of Chaucer. She was convinced that Emily was a student of Chaucer from certain medieval terms used in Emily’s letters to the Morpeth Herald, and from certain letters signed ‘Faire Emelye’. (Faire Emelye is a character in The Knight’s Tale.)

In 2012, Morpeth Soroptimists were contacted during an event by the great-niece of two of Emily Wilding Davison’s schoolfriends. Her name was Irene Cockroft, and we spent a delightful two days discussing her great aunts’ schooldays. Their names were Ernestine and Emily Bell, and wonderfully their story sheds light on the moniker ‘Faire Emelye’. They, like Emily, would become suffragettes. The story that has been handed down in Irene’s family is this: that Emily Wilding Davison had played the part of Chaucer’s Faire Emelye in a school play (adapted from Mrs Haweis’ book Chaucer for Schools), and that from that day on her schoolfriends called her the same (partly to distinguish her from Irene’s great-aunt Emily, who was dark-haired). Ernestine married Dr Herbert Mills and became a distinguished enamellist who designed suffragette brooches and badges. Ernestine also designed the first London Soroptimist badge.

Irene Cockroft brought her original copy of Mrs Haweis’ book with her. Inside is a drawing, ‘Faire Emelye picking flowers’, and from this picture, and the play, grew Emily’s passion for Chaucer.

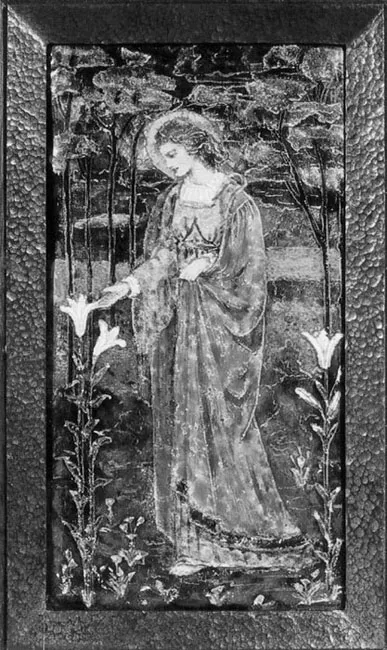

There were to be still more surprises for me before Irene left. She told me more about Ernestine’s fabulous artwork, and that Ernestine had in fact created an enamelled icon of Emily, shown as a Joan of Arc figure. She has generously allowed me to use it in this book, saying, ‘Here, Emily wears a celestial blue cloak among Madonna lilies, symbolising purity and chastity. There are colour notes of purple, white and green, the colours of militant WSPU suffragettes. Small marks on the cloak indicate fleur de lis, symbolising that ‘Faire Emelye’ has adopted the cloak of St Joan [of Arc]. The enamel image surround is copper or bronze.’

The ‘Faire Emelye’ enamel on plaque, c.1914. (© Ernestine Mills (1871–1959); image courtesy of V. Irene Cockroft; photography © David Cockroft 2000)

To discover more about Emily’s schooldays, I contacted the staff at Kensington High School for Girls, who were surprised and delighted to learn that Emily was one of their old girls. Indeed, they focused their Founder’s Day celebrations, on 25 January 2013, around a suffragette theme, and several of Emily’s descendants attended. The staff at that school then sent on an email from Becky Webster, Deputy Archivist of the Girl’s School Trust at the Institute of Education, University of London, sharing more about Emily’s schooldays through their records:

Date Enrolled: 3 November 1885

Parent: C.E. Davison of 7 Nevern Road, Earls Court

Former school: School of Lausanne at the premises of William Fenwick, Russell Square

1889: [distinction from] the College of Preceptors (probably their secondary examinations for pupils)

1889–1891: The Higher Certificate

Date of leaving: July 1891

Details from the logbook:

Page 59: Emily is listed as completing the College Preceptor’s examination in 1890 (Passed Class II – Division II)

Page 71: Passed the drawing examination, summer of 1887 (Division II)

Page 76: Marked as ‘H’ (meaning honours), drawing examination, summer of 1888 (Division III)

Page 81: Honours, drawing examination, summer of 1889 (Division IV)

Page 85: Honours, drawing examination, summer of 1890 (Division V)

Page 99: Prizes for English, French and Latin in 1889

Page 101: Prizes for French and Latin in 1890

Page 103: Prizes for English and French in 1891

Page 104: Gained the complete Higher Certificate, passing scripture, French (with distinction), German, elementary mathematics, literature (with distinction), and drawing in 1891. This is the most subjects of any of the girls listed – drawing being the additional subject.

What a fascinating glimpse of Emily the young woman, here just two years before her father’s death and a move to Northumberland.

In 1891, Emily began her September term at Holloway College. Six months later, another difficult time for the Davison family began with the announcement of the divorce of Emily’s sister Amy Septima on 30 July 1892. Amy Septima Briscoe (née Davison) and her husband, John George Briscoe, came to court in Briscoe versus Briscoe. It is probable that Amy Septima would not have had any means to pay the costs of the divorce. Though her husband was himself not above blame, the fault was placed on Amy’s side: her husband was robustly pursuing the case after he discovered that Amy had had a weekend dalliance with a gentleman friend in Haslemere. Though Charles E. Davison was in no way liable for the costs of Amy’s divorce, it is possible that the family, to save face, rallied around Amy and met her costs. The distress and upset caused...