![]()

ONE

The Aquitaine Succession

Eleanor was just fifteen years old in May 1137. At an age that was considered adult for either sex she had the poise and confidence that came from having ridden with her father Duke William X1 of Aquitaine for hundreds of miles in the same direction without meeting a soul who did not owe him allegiance. She was beautiful, she loved music and dancing, poetry and song. In a time when few men and fewer women could read, she was also literate in three languages and mature beyond her years.

Eleanor’s grandfather had used force of arms to weld the dissident barons of south-west France into a restive aristocracy that acknowledged his authority, but he had also been the greatest European poet since the fall of Rome, whose verses were declaimed and sung from the Atlantic to the Holy Land and beyond. A man of many contradictions, he had been the most courteous of suitors but also a great seducer of women. He had both defied the Church and been on crusade to Jerusalem.

But her father was an unlettered warlord, who had spilled so much blood on campaign in Normandy the previous year that he had set out from the abbey of La Sauve Majeure on Easter pilgrimage to the holy shrine of Santiago de Compostela2 in Spain to purge his soul. This was in preparation for marrying the widowed daughter of his vassal Viscount Aymar of Limoges in response to his counsellors’ urging that it was time to ensure a male heir for the rich county of Poitou and the vast duchy of Aquitaine.

Eleanor had passed the weeks since his departure with her younger sister Aelith in the ducal palace of L’Ombreyra at the south-east corner of the city of Bordeaux, two teenagers amusing themselves in the huge warren of apartments, audience chambers and tiled courtyards shaded by fig and olive trees. Aelith was two years younger, but both sisters were aware this would be Eleanor’s last springtime of freedom before an arranged marriage to some rich and powerful prince. With their mother and brother dead and their father absent, the girls were flattered and courted by the young unattached knights of the ducal court, while minstrels sang with lute and lyre their grandfather’s praises of women and love.

In the north, such behaviour would have been considered scandalous intimacy. Here it was one of the normal pleasures of life. And the scandal was that the duke’s betrothed had been carried off by a neighbouring baron and forcibly married in his absence – a deed that would cost him dearly when William X returned.3

Then, at the beginning of May, everything changed. Maidservants came running through the palace with news that the knights who had accompanied Duke William X on his pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela had posted in haste past the monastery at Cayac and the great abbey of La Sainte Croix south of the city without stopping to give alms to the monks at the wayside. Once within the gates of Bordeaux they had ridden straight to the archiepiscopal palace in the south-west corner of the city, where they were closeted with the most powerful man in Bordeaux, the newly appointed Archbishop Geoffroi de Lauroux. But of Duke William there was no sign.

Within an hour Eleanor learned he was dead. A vigorous and healthy warrior of thirty-eight, he had succumbed to food poisoning or drinking contaminated water on Good Friday. His companions had borne him to the cathedral of Santiago and had him buried close to the high altar in clouds of incense and to the chanting of Latin plainsong. Their prayer, ‘Sant Jacme, membre us del baro que denant vos jai pelegris …’4 – pray for him, Saint James, this pilgrim baron lying here – was echoed in all the languages of Europe by the thousands of pilgrims present.

In front of trusted witnesses shortly before dying, William X had orally bequeathed everything to Eleanor. Although Aquitaine’s Roman laws permitted succession by the female line, there was in Poitou a custom of viage ou retour, by which a feudal domain might pass to the nearest collateral male relative in the absence of a direct male heir. Similarly, north of the Channel two years previously Matilda, the only surviving child of Henry I, had been deprived of the succession to the English throne by a majority of the Anglo-Norman barons preferring her cousin, Stephen of Blois, with the result that civil war divided the country. Eleanor’s father had therefore orally requested his overlord the king of France to take Poitou and Aquitaine under his personal protection, to confirm his elder daughter’s inheritance and to arrange both girls’ marriages to suitable husbands.

Since such wealth, power and beauty made Eleanor a highly desirable prey for any baron with the nerve by rape and a forced wedding to make himself the new duke of Aquitaine, William’s companions hurried back to Bordeaux, keeping the news of his death to themselves. The lack of a written testament being not unusual in those times of sudden death, Archbishop Geoffroi decided that his duty to the Church lay in executing William X’s instructions5 and dispatched an embassy of discreet bishops and barons to the court of King Louis VI.

To Eleanor’s question as to what he looked like, the answer was that all princes were handsome and brave, great lovers of women.

In those days a royal court was not a building, but wherever the monarch and his chancery staff happened to be. King Louis was at his hunting lodge near Béthisy in the forest of Compiègne where he had gone to escape the noise, the stench and the fevers of Paris in midsummer – and to die. In his prime, when taking the field in a war that lasted twenty-five years against his vassal Henry Beauclerc, duke of Normandy,6 or when fighting off external enemies like the German Emperor, he had been known as Battling Louis and ‘the king who never sleeps’. But his subjects changed this to Fat Louis as he fought increasingly bad health, rumoured to be the result of his mother attempting to poison him in childhood.

By the summer of 1137 his body was so swollen by fluid retention that he could no longer bend down to put on a shoe, never mind wield a sword or mount a horse. The doctors and apothecaries of Paris had tried every remedy they could think of. ‘He drank so many kinds of potions and powders … it was a miracle, the way he endured it’, as a contemporary wryly remarked.7

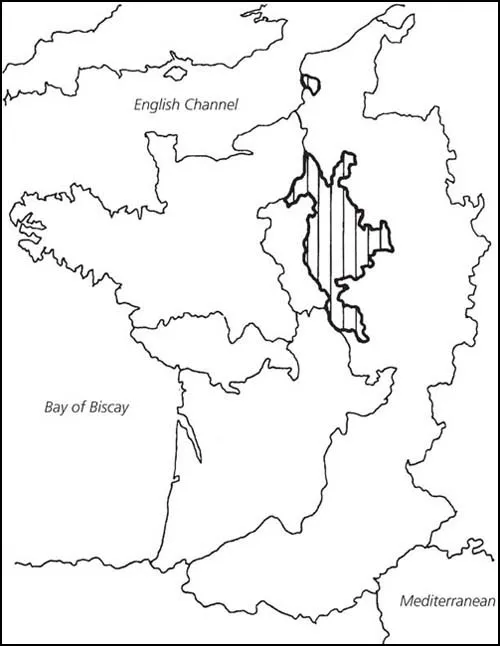

The king of France was fifty-six, a ripe old age for the time. For twenty-nine years he had excelled at the balancing act which was the lot of a Capetian monarch, several of whose vassals controlled far more territory directly than the royal domains, which lay mostly in the area around Paris later known as Ile de France.

The Capetian royal domains.

Astute and far-sighted, Fat Louis had made his court a model of feudal justice and his capital a seat of learning, with Paris the only university in Europe until the expulsion of the English students in 1167 led to the foundation of a university at Oxford. Had his eldest son Philip been alive to succeed him, he would have accepted death as a blessed release, for Philip had been an accomplished warrior. But he had been killed in a banal traffic accident when a startled sow, foraging in the garbage that littered the unpaved streets of Paris, ran between the legs of his stallion, leaving him paralysed with a broken neck in the filth.

Subsequently anointed heir to the Capetian throne on the advice of the chancellor, Abbot Suger of St Denis, Fat Louis’ second son was a very different person. Never was De Loyola’s dictum Give me a boy until he is six … more true. Young Louis, as he was called, had been raised in the cloister of Notre Dame for high office in the Church until catapulted by a sow’s panic to a place in history he would not have chosen. For the rest of his life, he oscillated between trying to be a strong king and behaving like the credulous, mystical monk he would have preferred to remain. Usually the monk won. When his father lay dying in the torrid summer of 1137, he was a deeply religious youth of seventeen, in whom Fat Louis saw none of the attributes of monarchy in that turbulent time of transition.

It must therefore have seemed an answer to his prayers when he learned from his old school friend Abbot Suger that the messengers from Bordeaux had arrived. After hearing their news, one name that cropped up in his private discussion with Suger was that of the handsome Count of Anjou, Geoffrey the Fair, whose lands bordered Poitou on the north and extended all the way from there to the English Channel.

A great champion of the tournament circuit, he and William X had the previous year laid waste territory which Fat Louis claimed in the Vexin – a disputed border strip that divided the royal domains from Normandy. Should Count Geoffrey learn too soon about the death of Eleanor’s father, there was every chance of him swooping southwards and adding Eleanor’s possessions to his own by marrying her under duress to his four-year-old son Henry. Once master of all western France, his territorial ambitions would be unstoppable.

The archbishop of Bordeaux wanted rewarding for the part he was playing; it was not too late for him to change sides. On his behalf the archbishop of Chartres demanded complete freedom for the Church in Aquitaine from all feudal and fiscal obligations, with the election of future bishops and archbishops to be according to canon law and free of influence by any temporal overlord.

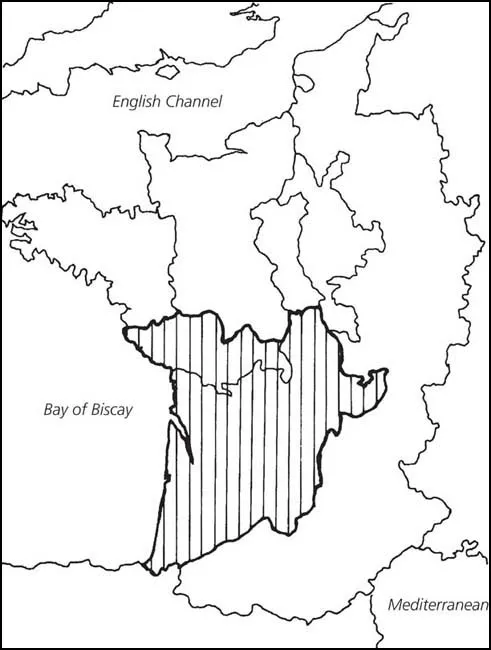

Eleanor’s inheritance of Poitou and Aquitaine

The right to appoint bishops was a contentious issue that was splitting Church from state all over Europe. Known as the investiture contest, it had been at the root of William IX’s excommunication, for to his mind and that of continental nobility, a bishop was a vassal like any other, to be chosen by his temporal overlord so that in return he owed advice in council and support in the field with his own armed forces when called upon to give it.

That Fat Louis immediately acceded to Geoffroi de Lauroux’s demands shows how crucial for the precarious Frankish monarchy was Eleanor’s vast inheritance – the south-western third of France, extending from the Atlantic coast inland to the extinct volcanoes of the Auvergne in the Massif Central. Any magnate who added this to his own possessions would destabilise the kingdom;8 on the other hand, if anything could give so inadequate a prince as Young Louis a chance of governing the kingdom, it was a wife whose dowry made him the richest man in France.

Eleanor and Young Louis being fourth cousins and therefore within the prohibited degrees of consanguinity, a prelate willing to marry them without first seeking a papal dispensation deserved reward. A charter granting all Archbishop Geoffroi’s demands was therefore prepared and witnessed by ‘Louis, our son already made king’9 and by Geoffrey of Chartres as papal legate, Bishop Stephen of Paris and Abbot Suger.10 And so the marriage between Eleanor and Louis was arranged as an affair of state without either of them being consulted.

To avoid the risk of Eleanor being abducted on the 400-mile journey to Paris, Fat Louis gave instructions for a royal cortège to travel to Bordeaux, making a show of force that would warn off the barons of Aquitaine. That Bordeaux was chosen for the wedding and coronation, rather than Limoges where the dukes of Aquitaine were traditionally crowned, suggests that it would have been dangerous for Eleanor to travel even that far unprotected. Or maybe Geoffroi de Lauroux was too shrewd to allow her to leave the city his knights and men-at-arms controlled until everything was doubly confirmed in writing.

Too ill to travel himself, Fat Louis decided not to billet the cortège by feudal right in the lands through which they travelled, but to pay for food, accommodation and forage for the animals. Although speed was important, the treasury was bare and such an expedition required financing by an especially promulgated auxilium or aid-tax on his vassals, which took time to raise.11 So it was mid-June when the prince set out with 500 Frankish barons and knights under Count Thibault of Champagne and Raoul de Vermandois, Young Louis’ cousin who served as steward of the princely household.12 Travelling with them to sort out any canonical problems were three of the best legal brains in France: Abbot Suger, Archbishop Hugh of Tours and the abbot of Cluny.

Behind the bishops, barons and knights rode the squires, leading the highly bred and trained destriers or warhorses. With the wagons of the sumpter train and the packhorses and mules laden with armour, weapons, food and tents, they constituted a small army of several hundred men and animals on the move. In addition there was a corps of foot-soldiers, but what limited the speed at which they proceeded across the drought-parched centre of France was the pace of the draught oxen. Each day billeting officers were sent ahead to find grazing or fodder and water for man and beast. Frequent ...