![]()

THE ARMIES

The Anglo-Egyptian Commanders

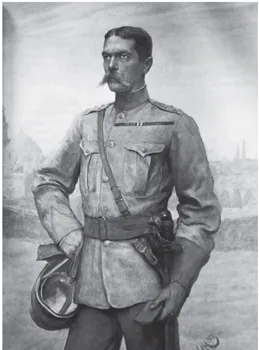

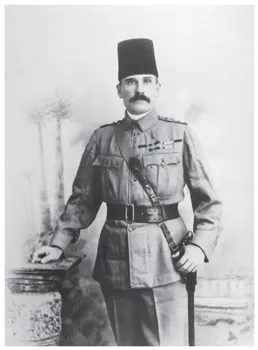

Sirdar (C-In-C) Major-General Sir H.H. Kitchener

Born into an Anglo-Irish military family, Kitchener entered the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich in 1867, where he met his lifelong hero, Charles Gordon. In 1870 he served as a volunteer with a French field ambulance in the Franco-Prussian War. Eleven years later he went on spying missions during the early stages of the Egyptian War. His abilities as an orientalist made him a natural choice as one of the first recruits to the new Egyptian Army in February 1883. After intelligence duties in 1884–85 he was made Governor-General of the Eastern Sudan (1886–88) and Adjutant-General of the Egyptian Army (1888–92) before his appointment as Sirdar.

Tall, with light brown hair parted in the middle, a wavy almost blonde moustache and blue eyes, Kitchener was an imposing figure. Brusque, dour, cold, even brutal, he made enemies easily. He was incapable of delegating even simple tasks, and could be cruel to the few staff he had. A strict routine meant that he liked to get through at least three hours of work before breakfast. His drinking was temperate, his uniform spotless and he would go into a rage if anyone touched his papers. He detested failure, weakness and even sickness in others – and himself. He also did not aim to be popular amongst the troops but in time they came to revere him.

4. Major-General Sir Horatio Herbert Kitchener, painted by H. von Herkomer. As Sirdar of the Egyptian Army and Commander in Chief of the Sudan re-conquest, it fell to him to avenge Gordon’s death.

Beneath his outward reserve Kitchener felt the pressures of what he was expected to achieve. ‘You have no idea what continual anxiety, worry and strain I have through it all,’ he told a friend in 1897. Those working closely with him had mixed opinions; Hunter (see below) once raged that his superior was ‘inhuman, heartless with eccentric and freakish bursts of generosity … a vain, egotistical mass of pride and ambition, expecting and usurping all and giving nothing.’

Both the Consul-General in Cairo, Sir Evelyn Baring (raised to Lord Cromer in 1892) and Lord Salisbury in London respected a soldier who ‘did not think that extravagance was the handmaid of efficiency’, though one biographer has said that Kitchener ‘accepted the need for parsimony with a whole heartedness which suggested at least a measure of relish.’ His training as an engineer allowed him full rein on the campaign to work out his superb logistical organisation of supply and transport. Aloof, intelligent, over-seeing all and divulging only what he thought necessary, men praised him as an automaton. The Daily Mail correspondent G.W. Steevens felt Kitchener ‘ought to be patented and shown with pride at the Paris International Exhibition. British Empire, Exhibit No. 1, hors concours, the Sudan Machine.’

5. Major-General Sir William Gatacre, the unpopular commander of the British Infantry Division.

Major-General Sir W.F. Gatacre

The commander of the British Infantry Division was a 55-year-old martinet who had served previously in the Hazara Expedition of 1888 and Chitral Relief Expedition both on India’s north-west frontier. Known to the troops as ‘Backacher’, because of his fondness for drill, Gatacre was ‘universally unpopular’ with Tommies and fellow officers alike, though Kitchener admired his perfectionism and said he was ‘just the right man for the job.’ A subaltern writing home disagreed and said Gatacre was ‘a gasbag … who talked drivel … and would make a splendid corporal … the general opinion is that he ought to be locked up.’ Neville Lyttelton, who commanded one of the two brigades under Gatacre, fairly summed him up as ‘brave as a lion, and I never came across such restless and untiring energy. No day was too hot for him, no hours too long, no work too hard. But he was very very jealous of authority, he wanted to do everything himself, and was very fond of the sound of his own voice.’

Colonel (Acting Brigadier-General) A.G. Wauchope

Wauchope was a 53-year-old Scot who commanded the 1st British Brigade and had made a habit of getting wounded in battle. He had seen action during the Ashanti War 1874, at Tel-el-Kebir and against Osman Digna in the eastern Sudan in 1884–85, on each occasion with his beloved Black Watch Regiment. Lyttelton thought he was ‘the direct opposite of Gatacre, equally brave, but very quiet and reserved. It was amusing to see him listening to Gatacre’s harangues, looking pensively at him with a far-away gaze as if he saw something through and beyond him.’

6. Colonel (acting Brigadier-General) Andy Wauchope, the intensely Scottish commander of the 1st British Brigade.

Colonel (Acting Brigadier-General) N.G. Lyttelton

The commander of the 2nd British Brigade was a relative of Gladstone and considered one of the rising brains in the British Army. The 52-year-old had fought the Fenians in Canada as a young officer and later served on the staff of the 1882 Egyptian Expedition. He would become Commander-in-Chief, South Africa, 1902–1904 and then Chief of Staff and First Military Member of the Army Council, 1904–1908. He was appointed Governor of the Royal hospital, Chelsea, in 1912, where he died in 1931.

7. Colonel (acting Brigadier-General) Neville Lyttelton, the cool and perceptive commander of the 2nd British Brigade.

Lieutenant-Colonel R.H. Martin

Martin commanded the 21st Lancers, the only British cavalry regiment at Omdurman. After several years peacetime service in India, it was the 50-year-old officer’s first campaign. One of Kitchener’s staff officers described Martin as ‘sharp, active and keen’.

Colonel C.J. Long

Long commanded the British and Egyptian artillery at Omdurman. He was a 49-year-old gunner with experience of fighting the Afghans in 1879–80, reckoned to be equally brave, impetuous and ‘slow of speech’.

Commander C. Keppel RN

This Royal Navy officer led the flotilla of ten gunboats at Omdurman from the Zafir. Other officers included Lieutenant W.H. Cowan RN on Sultan and Lieutenant D. Beatty RN on Fatteh; all three later becoming admirals. Also on Zafir was Brev-Major Prince Christian Victor of Schleswig-Holstein, an officer of the aristocratic 60th Rifles and a grandson of the Queen.

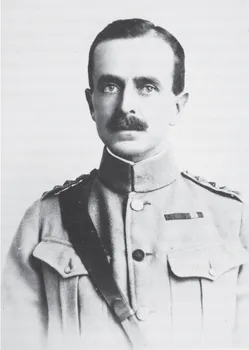

El Lewa (Major-General) A. Hunter

The commander of the Egyptian and Sudanese troops was described as ‘Kitchener’s sword-arm’. The dapper and dainty Archie Hunter was second-in-command of the Egyptian Army and thus the Sirdar’s deputy. A lowland Scot (though actually born in London), 41-year-old Hunter had joined the British Army at seventeen. Bored by peacetime soldiering and with no patron he had been delighted to join the Egyptian Army in 1884. ‘Hooray’ was how he took the news of the re-conquest, ‘Never was so pleased in all my life. The men are all in grand fighting trim.’ A fellow officer described him as ‘a real live Cromwellian, brutal, cruel, licentious, religious, brave, able, blunt and cunning.’ He was a no-nonsense soldier, devoted to his service, a realist who had a tendency to foolishly speak his mind at times, a man’s man who thought nothing of taking his Abyssinian mistress with him to Cairo.

8. El Lewa (Major-General) Archibald Hunter, the energetic and ruthless field commander of the Egyptian Army.

El Miralai (Colonel) H.A. MacDonald

‘Fighting Mac’ was the 45-year-old commander of the 1st Brigade, Egyptian Division. A Highland crofter’s son who had risen through the ranks as a result of his bravery and the patronage of Field-Marshal Lord Roberts, he had slogged from Kabul to Kandahar in a famous march of the Second Afghan War, then fought on Majuba Hill against the Boers in 1881 before joining the Egyptian Army in 1885. He had commanded the 11th Sudanese at Toski and the 2nd Brigade during the Dongola campaign. G.W. Steevens described him as ‘so sturdily built that you might imagine him to be armour-plated,’ but another journalist, T.P. O’Connor, displaying perhaps the class bias which dogged MacDonald all his life, said: ‘He was one of those men who ought never to have appeared out of uniform. He gave you the idea of strength and splendid manliness and bulldog power, but there was nothing of distinction in his air, in his manner or in his dress. He looked a Tommy in his Sunday clothes, which is not Tommy at his best.’ Officers serving under MacDonald found him to be as tough as old boots and no one doubted his guts on the battlefield.

9. El Miralai (Colonel) Hector Macdonald, the immensely popular, tough ex-ranker commanding the 1st Brigade, Egyptian Division.

El Miralai (Colonel) J.G. Maxwell

Maxwell commanded the 2nd Brigade, Egyptian Division. A big man, highly regarded as an efficient soldier, he had been ADC to General Alison, commanding the Highland Brigade at Tel-el-Kebir, and served with the River Column in 1884–5 before joining the Egyptian Army. Tact was not Maxwell’s strong point but he was known to be a good brigadier.

10. El Miralai (Colonel) John Maxwell, efficient commander of the 2nd Brigade, Egyptian Division.

El Miralai (Colonel) D.F. Lewis

Lewis commanded the 3rd Brigade, Egyptian Division; he had been wounded at the Siege of Eshowe during the Zulu War of 1879. Easy-going ‘Taffy’ was another seasoned Sudan veteran, having enlisted in the Egyptian Army in 1886.

El Miralai (Colonel) J. Collinson

Collinson had fought in Zululand and commanded the 4th Brigade, Egyptian Division, which was kept in reserve at Omdurman.

El Miralai (Colonel) R.G. Broadwood

This was the commander of the Egyptian Cavalry’s first campaign. The youngest of the commanders at 36 years, Broadwood had been promoted during the Dongola Expedition. He was well liked, a long-legged, dashing soldier whom even the acerbic Douglas Haig agreed was ‘a very good fellow and quite understands what the enemy and his own troops are worth.’

11. El Miralai (Colonel) Robert Broadwood who commanded the Egyptian Cavalry. He was described as ‘a very good soldier and fellow too’.

Kaimakam (Lieutenant-Colonel) R.J. Tudway

Tudway commanded the eight companies of Camel Corps. Another veteran of the Sudan War 1884–5, he had fought in the desert with ‘B’ Company MI Camel Regiment, and had been mentioned in despatches.

The Mahdist Commanders

Khalifa Abdullahi Al-Taishi

The ruler of the Sudan was about 50 years old at the time of the re-conquest. His father and grandfather had been holy men to the nomadic Baggara, the fierce and expert horsemen of south-west Sudan. Little is known about his childhood but he was close to his two full brothers and one half-brother. There is some dispute over whether he could read or write but it is accepted that he was not a good scholar. He was a slave for a time in his twenties but regained his freedom. Many times he had dreams of a Mahdi-deliverer and was one of Muhammad Ahmed’s first disciples on Aba Island. During this period he was described as being ‘tall, thin, somewhat pale … with a thin pointed face and big beard.’

Gaining supreme power on the death of the Mahdi, Abdullahi centralised the Mahdist state and set up a fair legal system. Kitchener’s intelligence officer Reginald Wingate, with his carefully organised propaganda, made continual sniping attacks on the Khalifa: he was growing fat by 1898, and it was said that he rarely left his house, the only two-storey one in Omdurman; he had broken the Koran and kept a harem of 400 attractive women; a huge negro was required to lift him into the saddle when he went to the mosque; and his son held orgies in his home.

Blinkered by his lack of education, believing totally in a war against apostates and unbelievers, Abdullahi was hemmed in by his own orthodoxy. In 1891 he had to defeat a plot by the Mahdi’s family to overthrow him. This only increased his rule by fear. However the Khalifa was never a real dictator because the Mahdi’s word was considered sacred law.

In debate it was said that Abdullahi often lacked self-confidence and needed his views reinforced by someone like his clever brother Ya’qub. It is hard to say what he might have achieved without the long wars against the British, Egyptians, Italians and Abyssinians along the Sudan’s frontiers. By 1895 the Sudanese currency was virtually worthless and trade had almost stopped.

Osman Digna

The most famous Mahdist general was a native of the Diqnab tribe of the eastern Sudan. This active 47-year-old had been well educated in Islamic law, theology and astronomy. He was a Suakin merchant until corrupt government troops impounded one of his caravans. Detained for trial, he s...