- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Birmingham was a renowned manufacturing centre by the 18th century and the city rapidly grew into the primary industrial centre of the Midlands. An account of Birmingham's heyday of heavy industry is recorded and the story is brought up to date with the story of the decline of heavy industry and its subsequent replacement by design, technology and computing. The proposed redevelopment of Rover's Longbridge site as a science park is symptomatic of this change.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Birmingham's Industrial Heritage by R.M Shill,Ray Shill in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire du monde. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

| Cars |

BIRMINGHAM AUTOMOBILE-MAKERS

Leon L’Hollier was prosecuted for speeding along the Stratford Road at Shirley on 22 December 1895. Police Constable Clifton related the case at a subsequent hearing before the Solihull magistrates. Mr L’Hollier had been found in charge of a locomotive that was travelling along the road at between 5 and 6 miles per hour and there was no licensed person preceding him with a red flag. Leon had broken the law as laid down by the 1878 Locomotives on Highways Act. This was the Act that regulated the movements of steam traction engines on roads but made no allowances for subsequent developments in road transport. It stipulated that three people were required to be in attendance, the speed was not permitted to exceed 4 mph, and only 2 mph was allowed in towns. Somebody had to precede the vehicle carrying a red flag and a licence was needed from each local authority through which the vehicle passed. Leon was driving an early version of the motor car. His defence lawyer argued that this vehicle was not a locomotive and that the 1878 Act had been devised to control the movement of the steam engine rather than the car. The magistrates, though sympathetic, decided that the law had been broken. However, they imposed the minimum fine of 1s plus costs.

Such were the restrictions on anybody using motor cars on British roads. It was a powerful deterrent for any innovative spirit. Automobiles made in France and elsewhere were imported into Britain, but the market was understandably limited. Leon described himself as a motorcar manufacturer of Birmingham and Maidstone, yet he is listed in trade directories as a perambulator-maker of Bath Passage in Birmingham. There was gathering opposition to the law as it then stood and a new bill was already before Parliament. The law was changed, during 1896, to remove the ridiculous restrictions and permit speeds of up to 14 mph. These changes were welcomed and enabled British manufacturers to enter the motor-car market. The Midlands very quickly became a major car-building centre, with factories in Birmingham, the Black Country, Coventry and Wolverhampton. Some of the earliest producers were established in Coventry during 1896. In Birmingham in about 1899 two firms, Lanchester and Wolseley, commenced commercial car-making.

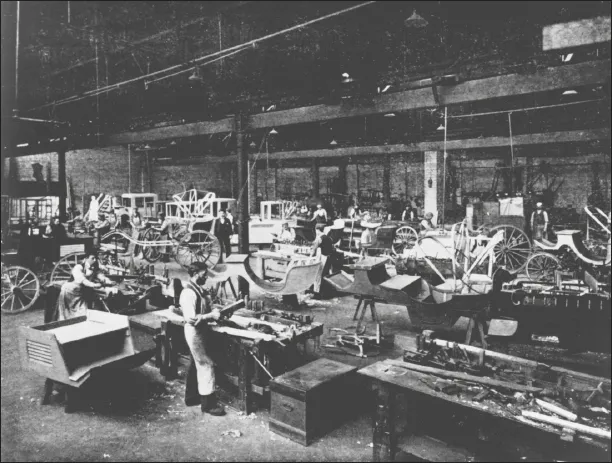

Early motor cars were called ‘horseless carriages’ and in many ways resembled the horse-driven version. Although the chassis and engine unit required special design, traditional coach-building methods were used to construct the bodies. Wood was then a major component. Some models had a beautiful finish through the lavish attention of the coach-maker. Layers of paint and varnish ensured protection from all climates, while inside special care was taken over the fittings and upholstery.

The Wolseley Sheep Shearing Co. of Sydney Works, Alma Street, were noted for the manufacture of shearing equipment, particularly for the Australian market. They also rank among the first producers of British automobiles. The person credited with this development was Herbert Austin who designed a three-wheeled vehicle which was exhibited at the Crystal Palace in 1896. His efforts led to Wolseley making other vehicles at their Aston factory from 1899 and eventually the creation of a separate firm, the Wolseley Tool & Motor Co., in 1901. They took over one of the largest and best-equipped factories in the town, which occupied a 3-acre site at Adderley Park. It had been built in the halcyon days of the cycle boom for the Starley Bros & Westwood Co. but had been closed when the cycle market fell on hard times.

BODY-MAKERS1

| Firm | Factory Locations | Dates of Operation |

| Birmingham Motor Body Co. | 2 Walford Road, Sparkbrook | |

| Bowden Brake | Kings Road, Tyseley | 1920– |

| Fisher & Ludlow | Rea Street & Bradford Street2 | 1920–47 |

| Fisher & Ludlow/BMC/BL/Jaguar | Kingsbury Road, Castle Bromwich | 1947–to date |

| Flewitts Ltd | Alma Road, Aston3 | c. 1906– |

| Forward Radiator | Cherrywood Road/Humpage Road | 1960–84 |

| Gordon & Co. | Taunton Road, Sparkbrook4 | c. 1914– |

| James Kane | 197 Moseley Road | |

| Mulliner’s Ltd | 10–11 Gas Street5 | c. 1885–1919 |

| Mulliner’s Ltd | Bordesley Green/Cherrywood Road | 1919–60 |

| John Shepherd Ltd | Cheapside and Sherlock Street |

Notes

1 This is a selective list – there were a number of carriage-builders, coach-builders and motor-body-builders in Birmingham that made vehicle bodies.

2 Fisher & Ludlow’s original works were in Rea Street (Albion Works). Other factories were established opposite in Rea Street, in Rea Street South, Barford Street, Bradford Street (Stonyard Works, 1930), Sherlock Street (No. 8, 1935), High Street (Bordesley, 1936), Coventry Road (1936) and Alcester Street (1937). The High Street premises were built on the site of Peyton & Co.’s bedstead factory. The Alcester Street works had previously been occupied by A.C. Sphinx, spark-plug-maker.

3 Flewitts Ltd was established as Martin & Flewitt, motor-body-builders, Lozells Road, but had transferred to the Alma Road factory by 1906.

4 Gordon & Co. was an established firm of furniture-makers with premises in Bradford Street.

5 Herbert H. Mulliner took over the coach-building works of William Findlater.

It was common practice for early car-makers to rely on the skill of others to produce the necessary components. These firms are better described as assemblers than makers. A few firms chose to make their parts on site and were true car-makers. The Wolseley company belonged to this second category and with the exception of specialist parts such as chains and tyres made the required car components in house. Many skilled workers in wood, metal, leather and upholstery were needed to assemble cars from the basic raw materials that came through the factory gates. The Wolseley motorcar works, as described by The Autocar (February 1902), was evidently well equipped for the time. The drawing office, which was above the floor of the main shop, was said to be ‘like a signal-box over a busy railway junction’. In the drawing office the draughtsmen converted the new ideas and designs of the works manager into scale drawings. When a new type of car was contemplated drawings were made to scale for every part, so that there was no possibility of the workmen making a mistake. Each drawing was translated by the pattern shop, which made patterns of all the parts to be cast. This work was reliant on the skill of the carpenter, and only experienced men were employed in this capacity. The patterns were used to shape moulds in fine sand at the foundry. Molten aluminium, gunmetal or iron was poured into these moulds, which when cooled formed the basic shapes for engine and other car components.

The interior of Mulliner’s coachbuilding factory in Gas Street and Broad Street, c. 1900. Factories such as these built and maintained the many types of horse-drawn vehicles that could be found on Birmingham’s streets in 1900. The traditional skills of the coach-maker were used to best advantage by the early car-makers. (Local Studies Department, Birmingham Reference Library)

The coach-smiths’ shop produced the metal frames of the wings, or mudguards, as well as other sundry ironwork. The wings were tried on a dummy frame and body so that there was no fear of fouling any moving parts of the car when they were assembled later. All the wings were built with the metal frame and then passed on to another shop where they were covered with stretched leather. The general smithy was in an adjacent shop where there were four hearths and a steam hammer. Here forgings for front and back axles were made. Radiators, tanks, hoods and exhaust pipes were produced in the coppersmiths’ shop. The radiators were made from copper tubes with brass gills that were stamped out and soldered to the copper.

The main shop was full of machines used for shaping and milling various metal parts that comprised the engine components. Within the erecting department complete engines were assembled and chassis were put together. The bare chassis frames were completed at one end of this shop and various parts were added as they were passed from one workman to another until the chassis construction was finished. The wood-working shop was the place where the wooden car bodies were constructed. All the work of forming, moulding, tenoning and sand papering was performed by machinery. Another process carried on at the works was upholstery, in which the seats and inside of the vehicle were suitably covered. The completed vehicle was then tested and passed on to the paint shop. This building was an isolated building free from the dust of the main factory. White enamel bricks lined it throughout.

This description may be worlds apart from the modern car factory, yet the basic tasks undertaken at this pioneer car plant were to be the model for future practice. While Herbert Austin was perfecting his car designs for Wolseley, Frederick Lanchester was experimenting with a design of his own. His brother Frank Lanchester was works manager for the Forward Gas Engine Co. when he first started experimenting with car design. Gas engines were a form of internal combustion engine, although generally large and cumbersome. Lanchester’s experience with this type of engine was to be a great help with his early efforts to produce a workable car engine.

The Lanchesters were joined by a third brother, George, and in the early 1890s they began to put their ideas into practice. In 1894 Fred Lanchester rented a small workshop at 12 Taylor Street, which was next door to the Forward Gas Engine factory. The prototype car was completed in 1895, and spurred on by its success Fred leased a plot of land at 33 Ladywood Road in 1897. On 30 November 1899 the Lanchester Engine Co. was formed. Frank Lanchester was appointed secretary, while Fred Lanchester became general manager. It was decided to purchase Armoury Mills in Montgomery Street, Sparkbrook, which had been formerly part of the National Arms and Ammunition works, although operations by this date had ceased. The remainder of the site was retained by the Royal Ordnance factory to service rifles.

The Armoury Mills became the new Lanchester works, but very soon further expansion was needed. In 1903 they took over adjacent premises known as the Radix Works. Chassis assembly and engine manufacture were carried on at the Montgomery Street factory. In 1903 they also acquired a site in Liverpool Street called the Alpha Works, which were used for coach-building and repair. During 1918 the company took over the Alliance Works in Formans Road, which had been built for Rudge Whitworth. They sold t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- One: Guns & Ammunition

- Two: Jewellery & Allied Trades

- Three: Buttons, Medals & Coins

- Four: Steel Pens

- Five: Glass-making

- Six: Lamps

- Seven: Engineering

- Eight: Metal Trades

- Nine: Electrical Trades

- Ten: Bicycles

- Eleven: Motor Cycles

- Twelve: Cars

- Thirteen: Commercial Vehicles

- Fourteen: Railway Rolling Stock

- Fifteen: Rubber Trade

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgements & References