![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

During the war between Charles I and his Parliament the city of Bristol, to quote the old Chinese curse, ‘lived in interesting times’ and was almost ruined by military action and the exactions of both sides. The ‘history’ of Bristol during this period has assumed an almost mythical quality which distorts perceptions of these events. This is not unique to the city as the English Civil War in general has often been presented in terms reminiscent of Sellar and Yeatman.

With the ascension of Charles I to the throne we come at last to the central period of English history (not to be confused with the Middle Ages, of course), consisting in the utterly memorable struggle between the Cavaliers (Wrong and Wromantic) and the Roundheads (Right and Repulsive).

Charles I was a Cavalier king and therefore had a small pointed beard, long flowing curls, a large, flat, flowing hat and gay attire. The Roundheads, on the other hand, were clean-shaven and wore tall, conical hats, white ties and sombre garments. Under these circumstances war was inevitable.1

With the possible exception of Cromwell’s campaign in Ireland, the war is often viewed as a romantic conflict, a gentlemanly affair fought between friends with the greatest of reluctance. A letter written by the Royalist Ralph Hopton to his Parliamentarian opponent William Waller illustrates this fellow-feeling between the two sides and incidentally provided the title for Ollard’s history of the war.2

The experience I have of your worth, and the happiness I have enjoyed in your friendship, are wounding considerations when I look upon the present distance between us. Certainly my affections to you are so unchangeable that hostility itself cannot violate my friendship to your person, but I must be true to the cause wherein I serve. . . . That great God, which is the searcher of my heart, knows with what sad sense I go upon this service, and with what a perfect hatred I detest this war without an enemy.3

Two weeks after the letter was written the armies commanded by these friends fought to a bloody stalemate at Lansdown. As with all civil wars this was a bitter, vicious conflict with up to 10 per cent of the adult male population under arms during the campaigning seasons of 1643, 1644 and 1645, and with 20–25 per cent serving in one army or the other during the conflict.4 It is estimated that 85,000 people died as a result of military action during the civil war with another 100,000 falling victim to disease.5 In addition excesses and atrocities were committed against civilians by both sides.6 Bristol’s citizens were to experience extortion, malicious damage, intimidation and murder during this ‘war without an enemy’, and would discover to their cost – on two occasions – what it meant to support the losing side in a civil war.

What was Bristol’s role during in this bitter internecine conflict? Control of the city was of critical strategic importance, as Clarendon explained after the Royalists captured the city in 1643:

This reduction of Bristol was a full tide of prosperity to the king, and made him master of the second city of his kingdom, and gave him the undisturbed possession of one of the richest counties of the kingdom (for the rebels had now no standing garrison, or the least visible influence upon any part of Somersetshire) and rendered Wales (which was before well affected, except some towns in Pembroke-shire) more useful to him; being freed of the fear of Bristol, and consequently of the charge, that always attends those fears; and restored the trade with Bristol; which was the greatest support to those parts.7

However, there is, even in the most recent history of this war, a tendency to minimize the city’s importance.8 I shall adopt a wider perspective, placing Bristol within the national context to re-evaluate its significance. While this book focuses on a single area, and therefore is a ‘local’ history, it will not be parochial in its view of the war or of the importance of Bristol to the Royalist ‘war machine’. Although their role was less romantic than that of Prince Rupert and his cavalry, the ordnance officials based in Bristol, the manufacturers who supplied them and the ships’ captains who ran their vital cargoes past the parliamentary patrols were equally important to the survival of the Royalist cause.

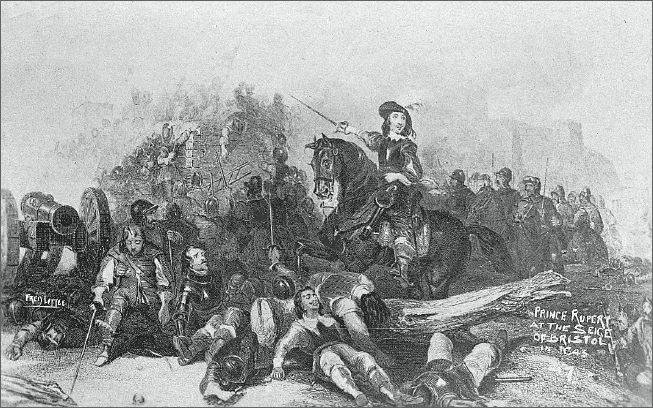

A typical myth about Bristol during the civil war concerns its capture by Prince Rupert in July 1643. Traditionally it has been accepted that Bristol was attacked by a Royalist army of up to 20,000 men and that William Waller had irresponsibly reduced the garrison to 1,500 infantry and 300 mounted troops, insufficient to man the defensive lines surrounding the city. It is further accepted that these defences were inadequate and that their weakness was compounded by a serious shortage of ammunition. Despite these problems the Royalists breached the defences by the chance discovery of a weak point unknown to the defenders. Once the line was breached the city was indefensible and the garrison commander, Nathaniel Fiennes, surrendered the city to save his troops and civilian population. Although this account was shown to be inaccurate shortly after the event it has retained some credibility.

Fred Little’s image of the capture of Bristol by Prince Rupert in 1643 illustrates the romantic view of these events that has tended to pass as history until recently. (Author’s Collection)

The myth was the creation of the man who surrendered the city, Col. Nathaniel Fiennes, and is first found in his reports to the House of Commons and the Lord General.9 Contemporaries were quick to challenge his version of events, as did a range of witnesses during his subsequent court martial.10 Despite this historians have continued to rely upon Fiennes, in part at least because one of the main Royalist accounts of the siege lends Fiennes credibility by extensively quoting from his Relation.11 Samuel Seyer, writing in 1823, based his account largely on contemporary documents and offered a range of estimates of the Royalist strength between 8,000 and 20,000.12 He credits the garrison with greater strength than Fiennes admitted, but presents Rupert’s success as almost a lucky chance and is so biased that much of the value of his work is undermined.13 Writing in 1868, Robinson accepted Fiennes’s statement as to the strength of the Royalist force and the governor’s assertion that the city was indefensible, although he does suggest that the garrison was stronger than reported.14 In Gardiner’s (1893) description of events at Bristol both the accidental nature of the Royalist success and the indefensibility of the city after the first breach are emphasized.15 Latimer, who made extensive use of both State Papers and City Archives, largely follows Robinson’s argument although he displays a strong pro-parliamentary bias.16 Wedgwood (1958) accepted that the garrison had been weakened to such an extent that it was no longer able to defend the city and that Fiennes was forced to surrender owing to lack of ammunition.17 Many historians, such as Rodgers and Young, accepted the myth without the reservations of Seyer or Latimer and simply repeat the details from Fiennes’s reports uncritically.18 The myth appears in both popular histories and the footnotes of works of impressive scholarship.19 The latest history at time of writing once again states that Fiennes had only 300 horse and 1500 foot against a Royalist force of between 14,000 and 20,000.20

Despite acceptance and repetition of this myth, the reality is more complex and intriguing. When he surrendered, Fiennes’s troops had successfully repulsed almost all the main attacks and Rupert’s men were bogged down in costly street fighting. The Royalists had suffered serious losses, particularly among brigade and regimental commanders, and the attackers were running out of ammunition. A new and intriguing question presents itself: why, in view of the military situation, did Col. Fiennes surrender one of the most important cities in England to the king’s forces?

Another myth is that the city was not of any great significance to the outcome of the conflict. Robinson told his Bristol audience in 1868, no doubt to their great disappointment, that those studying these events ‘must not attach undue importance to that city’.21 Likewise McGrath in 1981 minimized the significance of the city in the wider conflict:

Bristol in these years failed to play the important part that might have been expected from a large and rich port, and it had no relish for a civil war in which men were fighting for reasons which did not fill most Bristolians with any great enthusiasm.22

Once again this is a well-established tradition: as early as 1685 the pro-Royalist author of Mercurius Belgicus sought to minimize the significance to the Royalist cause of the recapture of Bristol by Parliament:

Bristol delivered upon conditions by Prince Rupert, after three weeks’ siege, part of the city won by assault; which the rebels gained not without some loss, so their loss no ways equivalent to the importance of the place.23

Conversely Clarendon, a member of the Royalist Council of the West, saw the loss of Bristol as a disaster:

The sudden and unexpected loss of Bristol, was a new earthquake in all the little quarters the king had left, and no less broke all the measures which had been taken, and the designs which had been contrived, than the loss of the battle of Naseby had done.24

The importance of the city in the minds of some Parliamentarians was evident at Fiennes’s trial.

The Parliament, his Excellency, London and the whole Kingdom, looked upon Bristol as a place of greatest consequence of any in England, next to London, as the metropolis, key, magazine of the west, which would be all endangered and the kingdom too by its loss. As a town of infinite more consequence than Gloucester, by the gaining whereof the enemy could be furnished with all manner of provisions, and ammunition by land, with a navy and merchandise by sea and enabled to bring in the strength of Wales and Ireland for their assistance.25

How important was control of the city of Bristol in deciding the outcome of the Civil War? The city was more than a garrison; it was a communication, administrative and manufacturing centre. The value of the port with its shipping and overseas contacts should also be considered, particularly in view of Royalist dependence on imported arms supplies. I disagree with those who maintain that Bristol played only a minor role in the civil war and certainly dispute Edmund Turner’s remark in 1803 that ‘it does not appear from the annals of Bristol, that anything particular occurred during the government of Prince Rupert’.26 Its capture by the Royalists in July 1643 allowed the king to continue the war, and its loss two years later dealt a devastating blow to his cause. It is also significant that both the commanders who surrendered the city were disgraced as a result, although both were well connected at the highest levels of their respective factions.

Another example of the confusion over Bristol’s role in the civil war concerns the city’s political allegiance. Contemporaries were confused, and confusing, in their descriptions of the loyalty of Bristolians in the 1640s. The Earl of Essex’s Scoutmaster, Samuel Luke, certainly received contradictory reports; in February 1643 Ferdinando Atkins, one of Luke’s agents who carried out reconnaissance missions behind Royalist lines, described the inhabitants of the city, which was under Parliamentary control, as ‘three parts’ malignants.27 By December Ralph Norton reported that the city’s Royalist garrison was convinced ‘that the town will rise for they are all Roundheads (they say) except the mayor and 2 or 3 aldermen, and that the townsmen run to Colonel Massey, and acquaint him with all things that happen there’.28 In the 1820s Seyer argued that the city was Royalist in sympathy, in part at least because of his own political opinions, while in the early years of the twentieth century, again influenced by his beliefs, Latimer argued that the city had favoured Parliament. In more recent times Patrick McGrath, in common with other researchers on the war, notably Underwood in his study of Somerset, argued that the political situation was far more complex and that neutralism was a significant feature.29 Interestingly, Underwood has since argued that neutralism in this period may not imply the absence of support for one party or the other.

p class="image">

Above and opposite: These 1920s artist’s impressions of Bristol during the civil war era contain some serious errors but give a good impression of what the city must have looked like. (Reproduced by kind permission of Bristol Central Library)

Neutralism, for example, was not always absolute. People might sensibly want to avoid risking life and limb, might wish to escape the war and till their fields in peace, and still prefer one side to the other. The preference might n...