![]()

Protect v.t. Keep Safe, defend, guard, (person or thing from or against danger, injury, etc.). Oxford Dictionary

one

The Bomb

From the end of the Second World War Britain embarked on a number of expensive defence projects, but none were as technically difficult or controversial as the production of nuclear weapons. This came at a time when the country was bankrupt and the United States was embarking on a policy of ‘non-proliferation’, so why did it happen? It would appear that Britain’s obsession with the ‘bomb’ had everything to do with world power status, something that was dwindling away as the Empire slowly disintegrated. To gain membership to the nuclear club a number of highly complicated obstacles had to be jumped, made all the more difficult for Britain since there was no help from across the Atlantic. However, these obstacles were cleared and Britain developed both a fission and fusion capability by 1957, becoming the third country to do so. This chapter will follow those political events that forced independent development of both warheads and describe the weapons in which they were employed. Also described are the delivery systems the British jointly operated or purchased from America.

Trinity

On 16 July 1945 the world entered a new and dangerous age, the testing of the first atomic device, Trinity. The Los Alamos team, headed by General Leslie Richard Groves and scientist Robert Oppenheimer, provided the United States with the power of life or death over any chosen city. Churchill was consulted on the possible use of the weapon as had been agreed at the 1943 Quebec Conference and on 4 July he gave it his formal blessing. At the Potsdam Conference, in Berlin, following the afternoon meeting on 24 July, Truman explained to Stalin and Molotov that the Americans were in possession of a new and powerful explosive. Stalin was unimpressed, suggesting it be used as soon as possible, convincing Truman that the USSR did not fully comprehend the situation; nothing could have been further from the truth.

The Soviet Union had pledged to declare war on Japan on 15 August 1945, and whilst it was recognised this would speed up capitulation, it would also complicate post-war sovereignty issues. The Russians had already reneged on agreements made regarding the future of Poland and the Baltic States, and a major Soviet influence in Japan would be an unacceptable price to pay for their involvement. Moreover, an American invasion of the Japanese mainland had been scheduled for 1 November 1945, but casualty estimates ranged from 40,000 to one million men; this too was clearly unacceptable. With the bomb America now had the power to finish Japan before Stalin advanced too far and without major loss of Allied life. Truman had only one option, however distasteful – use of the atomic weapon was authorised.

On 6 August, ‘Little Boy’ razed the town of Hiroshima to the ground. The explosion, at around 600m and with the force of 13,000 tonnes of TNT, killed an estimated 100,000 civilians immediately; many more thousands would die in the ensuing months and years from the effects of radiation poisoning. Just two days later Stalin declared war on Japan and invaded Manchuria, conscious that Hiroshima could well signal the end of hostilities and his aspirations for a foothold in the Pacific. On 9 August ‘Fat Man’ was released over Nagasaki adding another 80,000 dead and injuring at least 60,000. Convinced there was no defence against this deadly new weapon, the Emperor of Japan indicated his intention to surrender on the 10 August and terms were signed four days later.

During the Potsdam Conference Churchill was voted out of office, being replaced by Clement Attlee. Difficulties for the British were now on the horizon. The former American President, Roosevelt, had agreed to collaborate with Great Britain on a number of projects, including nuclear weapons. Unfortunately this had been a verbal arrangement with Churchill. Now both men were gone and with them, as far as Washington was concerned, went any secret wartime agreement, especially those that had not passed before Congress or the Department of State.

The Manhattan Project had been shrouded in secrecy. Yet this had not stopped security breaches and in 1946 a major Russian spy was uncovered, Alan Nunn May; unfortunately he was a British scientist, and he would not be the last. It transpired that Stalin had received practically all the information needed to start his own programme a clear month before the Trinity detonation. The discovery of espionage so close to the United States nuclear project was to damage British chances of information and co-operation throughout the late 1940s and early ‘50s.

Many in Truman’s administration displayed open contempt for what they considered to be shoddy security services, pointing the finger at MI5 and MI6, but spies were not the end of the story. By 1 August 1946 Britain had been sidelined by the McMahon Act, which placed nuclear development under the control of the Joint Atomic Energy Committees. More importantly for the British the McMahon Act halted all co-operation and information exchanges; the door had been firmly closed in Britain’s face.

As American weapon production increased, more demand was placed on the limited natural resources available, especially uranium. One of the major producers was the Belgian Congo, and Britain’s access to this resource was politically better than that of the Americans; the Joint Atomic Energy Committees (JAEC) were outraged. After denying the British programme any help it now looked like America would now have to rely on them for natural uranium ore. And if this wasn’t bad enough the British had one more hurdle for the Americans to clear. They held a veto over using atomic weapons against foreign countries. This had been agreed between Churchill and Roosevelt in 1943, becoming known as the Quebec Agreement, and effectively allowed one country the right to veto the other using atomic weapons. Again the JAEC had no idea such an agreement existed as it had not passed through Congress. Now it seemed America would also need permission to use her weapons; clearly Washington needed to act.

The problems with uranium would be hard to address but the Quebec Agreement, an unratified treaty between past leaders, was much easier to deal with. Washington decided that a technology package built within the Marshall Plan should include the resumption of co-operation between the two countries, as long as Britain gave up its veto. Britain readily agreed to the package but in the event received little information, and certainly none that would help the weapons programme. On 29 August 1949 the Soviet Union successfully detonated its first atomic device a clear two years before Western predictions. Politicians in the West started talking again; clearly Britain now warranted help if it was to make a stance against perceived Russian aggression. But this was not to be, as the talks collapsed dramatically when in February 1950 Klaus Fuchs, a scientist who had worked on the Manhattan and other nuclear projects, was exposed as a Russian spy. America’s security suspicions were confirmed: how could any sensitive material be shared if it could be passed straight to Soviet controllers? The talks were shelved indefinitely. Britain would now have to develop its own weapon if the world position it so coveted was to be maintained.

British Genesis

The architect of the British nuclear programme was undoubtedly William, later Lord, Penney. Penney was part of the British Mission at Los Alamos and had been a lynchpin in the development of the first atomic devices. It has been internationally recognised that the British team shaved almost a year off the programme. On returning to the United Kingdom Penney was invited to design a British atomic bomb programme, being appointed Chief Superintendent Armament Research in 1946. Sites at Harwell under Dr John Cockcroft and Risley under Christopher Hinton were opened late that year. January 1947 saw the British Government authorise the development of the first nuclear weapon and in June of that year the design process started at Fort Halstead under the direction of Penney. The department was given the title High Explosive Research (HER). However, it was soon clear that Fort Halstead was not the ideal site for developing the weapons programme and in 1950 the former RAF airfield at Aldermaston was selected to house the new HER laboratories. In 1952 it was officially named the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment (AWRE).

By the beginning of 1952 Britain was looking for somewhere to test the first nuclear device, and an American test range seemed the obvious choice. But representations to Washington requesting the use of a Pacific test site fell on deaf ears. The administration rejected the idea, and certainly didn’t put the request before Congress for fear of a riot; the Fuchs affair was still fresh in the mind of many. However, the Australians were far more receptive and allowed the use of one of the Monte Bello islands, starting a long association with Australia and the British nuclear weapons programme. Penney remarked at the time, ‘If the Australians are not willing to let us do further trials in Australia, I do not know where we would go’; luckily this was not to be. The first test was a logistical nightmare, optimistically scheduled for October 1952. Some of the major contractors were having major difficulties producing equip-ment to such a tight schedule. The high explosives needed for the compression system were being produced by the Woolwich Arsenal and would be ready on time. But problems were being experienced producing enough plutonium to mould the test device’s core. The Windscale site in Cumbria had been built specifically to produce weapons-grade plutonium, its two reactors going critical in 1951, but this left little time to produce the required amount of material for the test shot.

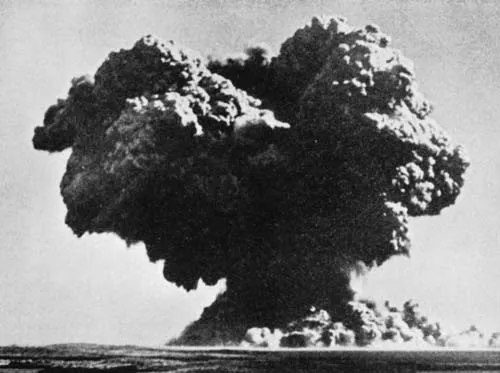

Hurricane, Britain’s first atomic detonation. (© Crown Copyright)

The device minus its plutonium core was loaded into a redundant River Class frigate, HMS Plym, and shipped under escort to the test site in June 1952. Windscale managed to produce just enough plutonium to be shaped and the core was flown out to the test site with a day to spare. HMS Plym was moored in Main Bay close to Trimouille Island where the plutonium core was fitted to the device; operation Hurricane was ready. At 9.30 a.m. local time Britain stepped onto the nuclear stage.

Super

As the development of the fission weapons moved on apace throughout the 1940s, a group of American scientists were also considering the conclusions of an Englishman, Geoffrey Atkinson, working in Gottingen in 1927. He had theorised that solar energy could be created through the fusion of light-weight atoms. By the mid-1930s isotopes of deuterium or tritium appeared to be likely candidates. This work was not wasted on members of the Los Alamos team and by 1942 Edward Teller was considering the possibility of making the theory work; the difference was he would eventually attract the financial backing of the United States Government. Initially the concept of the fusion device had been dismissed as too complicated and expensive, especially since to trigger such a bomb successfully required an extremely efficient detonator. But the USSR’s successful detonation of an atom bomb on 29 August 1949 set the ball rolling for development of the ‘Super’, a thermonuclear device.

Things didn’t run smoothly at first. Requests by both Congress and the Military as to how long it would take to develop such a weapon were met with dismay by the majority of the scientific community. Practicalities suggested that the size of such a weapon would make it undeliverable. Also, tests were now being conducted with high-yield fission devices, around 500kt, which would more than do the job if used. Further, Rabi and Fermi, part of the lead A-bomb team, suggested such a weapon ‘was wrong on fundamental ethical principles’. Truman, however, was swung by the argument that the Russians would develop a thermonuclear device and Washington could not stand back and allow them to take the lead. A Soviet development programme was a certainty, not least because Klaus Fuchs, the spy at the centre of the A-bomb, had also worked for a time in 1946 with fusion theory. On 31 January 1950 Truman, after a ten-minute meeting with advocates of the device, approved the development of the thermonuclear weapon.

Physicist Teller and mathematician Stanislaw Ulam soon came up with the idea of a primary and secondary charge, basically an A-bomb to set off an H-bomb. By 1951 Teller had devised the ‘sparkplug’, the ultra-efficient burn of nuclear material had been discovered. Put simply, a cylindrical mass of thermonuclear material, deuterium, has a sub-critical stick positioned down the centre. The shockwave from the primary detonation then converges on the centre of the cylindrical mass. As it reaches the centre the wave decelerates, creating heat. This turns the plutonium stick super-critical, causing it to explode and forcing a shock wave outwards, pushing against the implosion. Equilibrium between both waves, if reached within the deuterium fuel, would cause a megaton-yield explosion. Radiation implosion had been discovered and the stage was now set for a new period of test and development. It would take the British team four long years to reach this stage.

Testing of the first megaton-yield thermonuclear device proved to be a logistical nightmare. The secondary device was to contain liquid deuterium with a boiling point of 23.5 Kelvin and to stop it vaporising prematurely a large cryogenic plant had to be built. The final device weighed in at 82 tonnes and was housed, along with the cooling plant and other test equipment in a four-storey-high ‘shot house’, which could have been quite easily used to park aircraft. Over 500 monitoring stations were established and around 11,000 personnel had to be billeted for the duration of the tests. On 1 November 1952 at 07:14 ‘Ivy Mike’ detonated with a yield of 10.4 megatons. The small island of Elugelab at Eniwetok Atoll, part of the Marshall Islands, was replaced by a mile-wide crater 200ft deep. The Soviet Union tested an air-deliverable weapon just nine months later and by 1955 both sides had true thermonuclear devices. Churchill was later prompted to describe the situation as the ‘delicate balance of terror’.

Grapple

All Britain could do as both superpowers ran to the thermonuclear finish line was spectate; clearly if it was to remain a major player on the world stage something would have to be done. In 1954 it was decided that once again Britain would have to go it alone, developing a totally indigenous hydrogen bomb. Many in the Government had mixed feelings, but this did not deter Churchill from approving the plan, even at a projected cost of £10 million. Ironically this was ultimately to lead to closer ties with the United States, form the backbone of the 1957 Defence White Paper, which was so detrimental to British Air Defence, and see the formation of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

The Grapple series of atmospheric tests, between 1957 and 1958, at Christmas Island and Malden Island in the Pacific, ushered the United Kingdom into the thermonuclear age. However, more importantly they were used to demonstrate Britain’s capability to the world before an expected moratorium on atmospheric tests came into force. The first of a number of two-stage designs, ‘Short Granite’ was dropped by Vickers Valiant XD818, piloted by Wing Commander Ken Hubbard, on 15 May 1957 at Malden. The device, carried in a Blue Danube aerodynamic fairing, achieved a yield of around 300kt, well below the intended 1-megaton yield for one ton in weight; but the concept had been proven, and development continued. Incidentally, Valiant XD818 is now the only surviving complete example of its type and currently resides at the Royal Air Force Museum, Hendon.

The nuclear stores at Upper Heyford. Special weapons were stored here from the 1950s through to the signing of the INF treaty in 1988.

By October 1957 the build-up for additional tests at Christmas Island were well under way. Equipment for the new shot ‘Grapple X’ was being flown out in a number of chartered Australian aircraft, whilst personnel were flown, this time on the newly acquired de Havilland Comet, out to Edinburgh Field, just outside Adelaide, before being ferried to Christmas Island in rather older Hastings transports. On 28 October an instrumented inert bomb was dropped over the island as part of a full scientific rehearsal. Weather delays put the live drop back three days, but on 8 November 1957 Grapple X got the green light. At 8:45 Valiant XD824, piloted by Squadron Leader B. Millet, dropped Britain’s first true thermonuclear device, achieving a yield of 1.8 megatons. By April 1958, the largest ever British test, ‘Grapple Y’, achieved a yield of 3 megatons. America started to take notice.

Moratorium and Membership

Whilst the technological prowess of the United States, Soviet Union and, later, United Kingdom became self evident there were many who considered the escalation...