![]()

1

Creating the Gothic Image

On the morning of 6 September 1174, the bewildered monks of Christchurch Priory stood amid the smouldering ruins of their beloved Romanesque Quire, finished only forty-four years before. They were in no state to come to a considered – far less to a united – decision about what should replace it.

This cloistered community had survived four tumultuous years since the notorious murder of their Archbishop, Thomas Becket, in December 1170. After his hurried burial – in the face of his enemy de Broc’s threat to throw his body to the pigs – the cleansing and reconsecration of the Cathedral had followed. The growing flood of pilgrims and miracle stories, and the rapid canonisation of their St Thomas in 1173, had culminated in King Henry II’s spectacular public penance and chastisement the following year. Now, just two months later, sparks from a fire outside their gates had grown unseen above the Quire’s wooden ceiling, which had collapsed on to the wooden stalls below, consuming everything. A plethora of problems, pressures and choices lay before them.

Thanks to Lanfranc, the Conqueror’s Archbishop, Canterbury’s primacy over York and the rest of the English Church had been acknowledged in 1072 by the Accord of Winchester. Meanwhile, from the expanded monastery here, bishops and abbots were promoted – the instigators of a programme which would eventually see all existing cathedrals rebuilt in massive Anglo-Norman Romanesque. Several rural sees were moved to towns, making their new cathedrals even more obtrusive. They became the visible ‘stone jack-boot of conquest’, as Ian Jack describes their impact. Supreme in Church matters, Canterbury was also the natural link between London and France, where many of the kings’ lands and concerns lay. The monks knew that what Canterbury did today, others would follow tomorrow. Their extensive manorial estates would provide resources enough for rebuilding. So what was needed?

Obviously, a magnificent shrine for their new saint, with ambulatory space around it for pilgrims, must be added, east of the monks’ Quire and presbytery. This greatly extended east end would be revolutionary in itself, compared to traditional Romanesque. But already in France, Abbot Suger at St Denis near Paris had rebuilt that pilgrimage church in a revolutionary style. Suger was an unlikely man, at least at first sight, to be the moving spirit behind the adoption of Gothic. As a royal servant he had risen rapidly in the favour of King Louis VI, the Fat, to serve as an ambassador. He was rewarded with the Abbacy of the royal mausoleum and pilgrimage church of St Denis. After five years spent mainly in royal service, in the decade from 1127 to 1137 Suger reformed his monastic family and augmented the revenues of his abbey. Turning his attention to its fabric, by 1140 the west front had been rebuilt in Romanesque style deriving from the Arch of Constantine.

St Denis’ interior. The novel appeal of the Gothic style is perfectly illustrated at St Denis’ east end, completed in 1144. Light and height are achieved by the use of ribbed stone vaults and clustered columns. (© Sylvain Sonnet/Corbis)

It is impossible to tell what impelled Suger to change styles when the choir was reconstructed (between 1140 and 1144). A high, light space, surrounded by the curves of chapels radiating from an ambulatory, was created by employing for the first time five essential elements of Gothic architecture. To the ambulatory and its chapels were added pointed arches, ribbed vaults, flying buttresses and clustered columns, which, fifthly, allowed arches to spring from them in more than one direction.

Suger was so pleased with his creation that he wrote two books about St Denis in which he stressed that aesthetic pleasure was an extra and special way to bring the worshipper to God. Pugin’s writings in the early days of the Gothic Revival nearly 800 years later would draw the same essential conclusion. It is not surprising that St Denis was soon to be copied at two other pilgrimage churches, Laon and Sens, which lay on the important trade route between Burgundy and Flanders.

Such aesthetic and religious qualities promoted revolutionary structural changes, and specialisation began to emerge. Masons had previously travelled from patron to patron, working anonymously to the glory of God. Now the patron, the master mason and the craftsmen were all essential to the result. Anonymity would gradually give way to named masons; William of Sens was among the first. More importantly, through him the Quire of Canterbury Cathedral would be as revolutionary in England as St Denis in France. So how did it come about?

Becket, in fact, had spent most of the six years of his long exile at Sens, in close accord with its bishop whose successor, in turn, was the first and most active champion of Thomas’ canonisation. So, in time, among the masons surveying the job in Canterbury came William of Sens, who for twenty years had worked on Sens Cathedral, a strictly mathematical Gothic construct based on the proportions of height to length and width. While some masons said that the scorched pillars could be consolidated to replicate the old Quire, others said that total demolition was the only answer. William spent several days surveying the Romanesque outer shell which we still see today and talking with the various factions among the monks. Without revealing his gloomiest estimates of the probable costs, he proposed inserting a Gothic cuckoo into the Romanesque nest. This compromise appealed to those among the monks wanting economy and assuaged the fears of the traditionalists. The layout, designed to accommodate the constricting shell, produced the sinuous kink which makes Canterbury’s east end an advance on the severe classicism of Sens.

It was still a huge leap of faith for the monks to go for the ‘shock of the new’ with:

• Pointed, not round, arches

• Six-part stone vaulting instead of a flat wooden ceiling

• Thin, three-storey walls supported by concealed buttresses

• A clerestory row of windows below the vaults

• Clustered columns, some in dark-coloured marble, in place of massive pillars with varied decorative capitals.

After 1170 the Priory produced a stream of biographies, letter-books and miracle stories, but the most remarkable novelty was the monk Gervase’s survey of the Romanesque Cathedral he had known. He then described the fire, William of Sens’ appointment, and what William accomplished year by year until his tragic 50ft fall from the scaffolding while supervising the installation of the final boss of the new Quire.

It had taken eight months to clear the ruins, order materials and enlist French sculptors capable of carving, with the chisel, the uniform capitals of the new piers. Work finally began on 6 September 1175 and we can plot William’s progress from Gervase’s account. Two bays went up in 1175; a third bay, side aisles and a triforium in 1176. By the winter of 1177 the vaults were installed above the alternating plain and octagonal pillars, buttresses supported the increased height of the walls, and a pair of clustered columns were ready for the more intricate vaulting of the new eastern transepts. When William fell in the summer of 1178, eleven pillars 12ft taller than their predecessors supported an elaborate triforium – a mass of round and pointed arches, embellished for the first time with Purbeck marble shafts. New light came from the clerestory windows above and from the enlarged windows of the side aisles. Four-part stone vaulting there and six-part in the Quire stunned the monks: ‘they appeared to us and to all who saw them incomparable and worthy of praise,’ reported Gervase.

Cathedral Quire, north. Here is the junction between the work of William of Sens and his successor. This view takes the eye up to the elaborate triforium and light is thrown on the high stone vaults. (© John Kemp)

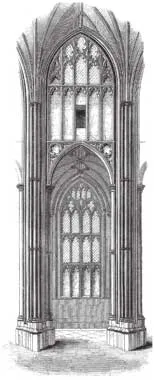

Cathedral Corona. Robert Willis’ meticulous drawing shows how far English William had developed the Gothic style at the east end, compared with the Quire.

During the three months in which William of Sens was carried on a stretcher to supervise his successor, English William, we cannot know in what detail he shared his plans for rebuilding the Trinity Chapel, the next part of the work after completing the transepts and presbytery. This was where Becket had celebrated his first Mass after his consecration and would be the site of his splendid shrine. Modern controversy continues over what was constructed eastwards of Pillar XI, but the successive steps, by which the pilgrim rises to this highest point, the Trinity Chapel, must be a legacy of William of Sens. Sens Cathedral had terminated at the east with a nine-part vault and radiating chapels. English William, at the Corona (an extension at the extreme east end), used a similar vault as a canopy over the reliquary containing the crown of Becket’s cloven head, which had won him a martyr’s crown. The Trinity Chapel itself seems to contain the best of both Williams, with its range of tall windows filled with jewel-bright glass telling the miracle stories (see colour plate 14). The light plays on the polished coloured marble of the piers surrounding the shrine.

Those groundbreaking extensions eastward required that the new eastern crypt should incorporate Becket’s original resting place. Between two polished marble pillars the coffin, encased in marble, would lie for fifty years until its translation in 1220 to the Trinity Chapel, where the miracle windows portray the original shrine. The eastern crypt today is where the shock of the new is most clearly felt. You emerge from the dark labyrinth of the Romanesque western crypt into English William’s high, light, vaulted space where pilgrims circulated in the ambulatory around the original tomb (see colour plate 1).

Many went home enthused to modernise their own churches. From Rochester to Chichester to Lincoln, Gothic would spread not only in whole buildings but in parts, as in the use of Purbeck marble at Salisbury. Uniform stiff-leaf capitals, larger pointed windows, and buttresses allowing for taller, thinner walls would follow across the country. After 1220, when at last Becket’s relics were installed in his magnificent shrine in the Trinity Chapel, the French Gothic Quire laid its own imperative on future rebuilders at Canterbury to somehow match its splendour.

The Nave

The state funeral of the Black Prince in 1376 prompted the monks to look again at Lanfranc’s small, dark 300-year-old nave and they decided to rebuild. Against the odds, over the next thirty years, a miracle was erected. In troubled times successive priors had to seek new royal and episcopal patrons; the outcome was a glorious Perpendicular space bathed in light from 40ft transom windows. Their first patron, Archbishop Simon of Sudbury, was murdered in the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381; and then a severe earthquake in 1382 virtually suspended work for nine years. Even the deposition of the open-handed Richard II in 1399 only led to greater support from Henry IV, his family and the Archbishop.

Following the Black Death mid-century, a general shortage of skilled masons and quarrymen contributed to the new solutions being designed by architects. Thin walls with big windows and strong buttresses; thin, clustered piers with shaft-rings; and small capitals in place of the labour-intensive carved foliate ones, created strong vertical lines culminating in high lierne vaults. The great exponent of this English Gothic Perpendicular style was Henry Yevele, the King’s master mason. In the intervals between redesigning the nave of Westminster Abbey, he was heavily involved at Canterbury. He had remodelled a Romanesque chapel in the crypt as a chantry for the Black Prince, who had willed to be buried beside it; in the event, Yevele designed the King a grander tomb on the south side of the Trinity Chapel, close to Becket’s shrine, while he was rebuilding the City’s Westgate for Simon of Sudbury. The Archbishop had meanwhile paid £2,000 to demolish the old nave from the western transepts to the western towers. It must have seemed natural to ask this ‘Wren of the fourteenth century’ to match the French Gothic of the long east end within the limits of the mere eight-bay space now cleared for his new English Gothic. Once it was agreed to continue the high roofline created at the east end by the raised Trinity Chapel as far as the west end, Yevele could compensate in height for the lack of length and width. When the high vaults were completed in 1400 they were 80ft from the floor, the side-aisle vaults being only 10ft lower. Work on the south aisle had begun by 1378. The walls, of Caen and Merstham stone, buttressed with Kentish ragstone, rose on reused foundations. Purbeck marble was still favoured internally and Simon of Sudbury’s arms (a talbot dog) adorn the vaults here, confirming their date. The north aisle could not follow on at once because the earthquake of 1382 had done such damage to the adjoining cloister and chapter house. When work picked up speed under Prior Thomas Chillenden in 1391, Yevele’s friend Stephen Lote, and his assistant John of Hoo, appear in the accounts as the principal masons. Shrewd management of the monastic estates allowed Chillenden to spend £3,000, augmented by the donations of Archbishop Courtney and King Richard II. Chillenden, with his charm, energy and financial acumen, is as responsible for the nave as its architect, patrons and masons. Yet it was only part of a building programme which left its mark all over the Precincts and in the great pilgrim inn, the Chequer of the Hope. He was long remembered as ‘the greatest builder of a Prior that ever was’.

Yevele died in 1400 but at the west end, near the huge new window, appear the arms of Henry IV and two of his sons. The usurping king was planning his own royal tomb opposite that of the Black Prince in the Trinity Chapel, and paying for the pulpitum screen. His Archbishop, Thomas Arundel, and Bishop Buckingham also contributed to the cost, since both planned tombs in the new nave; these were destroyed at the Reformation. Lanfranc’s floor still supports the nave’s towering fourteenth-century piers, as archaeologists revealed in 1993. Modern visitors can only marvel at this surpassing space; only the north view from the Green Court reveals how very short the nave is in comparison to the long eastern range (see colour plate 2).

Cathedral nave detail. This drawing from Willis’ Architectural History of Canterbury Cathedral accentuates the tall transom windows and clustered columns, without noticeable capitals of the early Perpendicular style.

The year 1970 marked the eighth centenary of the martyrdom of Thomas Becket. As part of many celebrations, new lighting was installed to articulate the lierne vaults of the nave. Yehudi Menuhin stationed himself 80ft below them to play unaccompanied Bach in the otherwise darkened nave. The marriage of the divine geometry of Bach’s music with Yevele’s architecture created for us the most magical of many such musical moments over the last half century.

Building Bell Harry Tower

The new nave, completed in 1405, became not an end but a beginning. The monks saw clearly that work was needed on the western transepts and on Lanfranc’s south-west tower. Thomas Mapilton, consultant to Canterbury Cathedral from 1423 to 1434, would supervise the work on both the south-west tower and the south-west transept. This busy man was a favoured mason of Henry V and became royal master mason in 1421 after continuing Lote’s work at Westminster Palace. He attracted Archbishop Chichele’s patronage and built the Lollards’ Tower at Lambeth Palace. Mapilton produced designs to rebuild both of Lanfranc’s Norman towers in Yevele’s Gothic style; in the event, only the south-west tower was completed, supervised by John Morys, warden of the ...