![]()

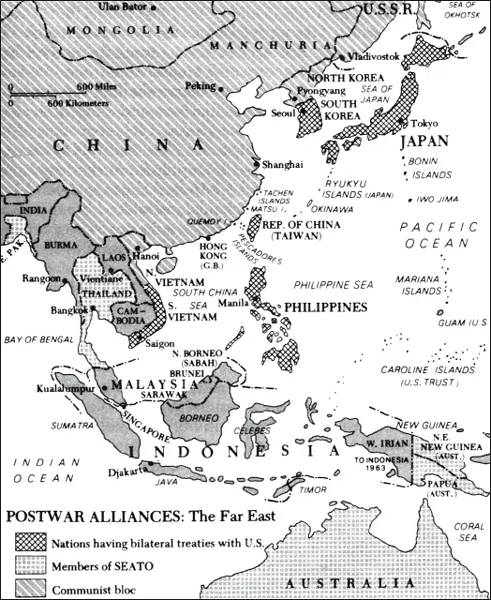

Map 1 Postwar alliances: the Far East

(From America: A Narrative History by George Brown Tindall. Copyright © 1984 by W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. Used by permission of W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.)

![]()

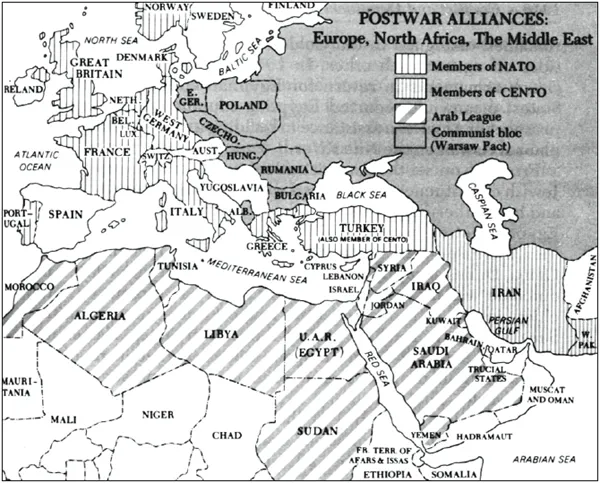

Map 2 Postwar alliances: Europe, North Africa, the Middle East

(From America: A Narrative History by George Brown Tindall. Copyright © 1984 by W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. Used by permission of W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.)

![]()

Introduction

The term Cold War generally refers to the ideological, geopolitical, and economic international rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union that characterized the period from approximately 1945 to 1991. These two states, respectively the world’s leading capitalist democracy and its most prominent Communist nation, were allies during the Second World War, but within a few years perceived and depicted themselves as locked in desperate competition, a conflict in which each antagonist sought not simply to prevail, but also to win the adherence of as many other countries as possible. The heritage of the Cold War continues to haunt the world today, symbolized by the fact that the current international system has as yet acquired no better descriptive label than ‘post-Cold War world order’.

The Cold War began when the successive impact of the First and Second World Wars had destroyed the prevailing international order of the early twentieth century. In 1900 several great European powers, pre-eminent among them the British empire, Germany, and France, together with Russia and a rising power, Japan, dominated the world. The United States had the economic potential to join this exclusive club but had not yet done so. All the great powers were monarchies and most had extensive colonial possessions, which in many cases they sought to augment. Western empires ruled the Middle East, Africa, and much of Asia. A rough balance of power existed among them.

By 1945 two major wars, conflicts that the American secretary of state Dean Acheson among others characterized as a two-part ‘European civil war’ in which the interwar years constituted only a truce, had altered this international system beyond recognition or possibility of restoration. The impact of the First World War helped to facilitate the emergence of totalitarian regimes of left and right, officially dedicated to enhancing the lives and self-respect of the general populace even as they imposed authoritarian controls over political, economic, and intellectual matters. In Russia the First World War brought the overthrow in 1917 of Tsar Nicholas I and the creation of the world’s first Communist state, the Soviet Union. In Italy in 1923 and Germany in 1933 the war experience and consequent economic and political dislocations contributed substantially to the emergence of Fascist regimes, respectively led by Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler, their stated objectives to restore their nations’ international standing and win them a place in the sun.

The Second World War, in many respects the result of German and Italian efforts to accomplish these objectives, reduced all European states to the rank of second-class powers, close to bankruptcy and suffering from severe physical war damage, while greatly enhancing the relative standing of both the United States and the Soviet Union. The United States emerged as incomparably the greatest economic power in the world, its industrial plant and superiority decisively enhanced from serving as the ‘arsenal of democracy’ which provided the matériel for the Allied war effort. Although German invasion initially inflicted severe damage on the Soviet Union, Russian economic potential and the sheer size of the Soviet military intimidated its smaller, war-crippled European neighbours. In Asia the war left Japan devastated and defeated and China gravely weakened and wracked by internal revolt and economic difficulties. In most Asian colonies forceful nationalist movements, of varying political complexions, emerged or waxed stronger during the war. These had discredited the European colonial overlords, depriving them of the financial, military, and ideological resources to maintain their grip on their imperial possessions, whose future governmental systems and international alignments generally still remained undetermined.

Historians have disagreed, sometimes bitterly, as to whether considerations of ideology, national security, or economic advantage predominated in causing the Cold War; over which nation, the United States or the Soviet Union, bore the greater responsibility for its development; and on the relative moral merits of the two major protagonists. The Cold War is perhaps best understood as the product of an international power vacuum in both Europe and Asia and of the tensions engendered by the gradual definition, demarcation, and delineation of a new balance of power. Much of the world was in flux as a new system, greatly affected by the developing bipolar Soviet–American antagonism which was both a cause and, increasingly, a self-generating consequence of the Cold War, emerged incrementally. This process took place at varying speeds in different regions, and throughout the Cold War local revisions were nearly always in progress.

In Europe a stable modus vivendi, which endured for over four decades, quickly emerged. In much of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, by contrast, the situation was far more fluid, the result of both the fundamental insecurity of numerous existing governments and the degree to which the Second World War weakened the European colonial empires. As Europe stabilized, the Cold War quickly shifted its focus from that continent to other regions, especially Asia and the Middle East. Despite the emergence of a consciously non-aligned group of states, the two great powers tended to perceive all international questions through the prism of their overriding mutual competition for predominance. This tendency led the United States to intervene in two major Asian conflicts, the Korean civil war which began in 1950, and the Vietnamese civil war which, in varying guises, continued throughout the three decades from 1945 to 1975.

One pronounced Cold War feature was the relative caution major powers displayed when dealing with each other. Despite mutual protestations of irreconcilable hostility, in practice the United States and the Soviet Union shared certain common interests, to the extent that one historian has termed the period ‘the long peace’. Although in Korea and Vietnam alike both the United States and the Soviet Union assisted opposing parties involved in direct hostilities, in neither conflict did either great power ever seriously consider any outright declaration of war against the other. Indeed, in both struggles restricting their intervention so as to preclude such an outcome was a prominent, if tacit, preoccupation of both major powers. The successive development of atomic and thermonuclear weapons enabled each big power to inflict near devastation upon its rival, but only at the cost of its own destruction. Consequently, from the mid-1950s onwards the two antagonists launched efforts to reach some understanding on the use of such weapons. The Cuban missile crisis of 1962, the occasion when a nuclear exchange seemed most likely, had a sobering effect on both big powers and, indeed, on the rest of the world.

Concurrently, the international scene became more complicated, challenging attempts at bipolar definitions. As defence budgets soared and innovative technology grew ever more expensive, attempts to reduce military spending appeared increasingly attractive. In 1949 the emergence of a Communist regime in China, a country with one-quarter of the world’s population, appeared a major victory for the Soviet camp, one likely to advance the Communist cause throughout Asia. Yet by the late 1950s growing hostility between China and the Soviet Union effectively divided the two major Communist powers, a situation which smaller socialist countries, such as Vietnam, could often manipulate to their own advantage. In the late 1960s and early 1970s the United States successfully exploited the intra-Communist split, symbolized by bloody Sino–Soviet border clashes in 1969, to move towards détente with both the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China, whose government American leaders had previously refused to recognize. The results included several nuclear arms limitation agreements, the relaxation of East–West tensions in Europe, and a de facto, albeit limited, Sino–American alignment.

From the later 1970s until the mid-1980s, a period one historian has termed the ‘second Cold War’, Soviet–American tensions again accelerated. In 1980 the election in the United States of a conservative president, Ronald Reagan, who vowed to combat what he characterized as the Soviet ‘evil empire’, seemed to herald a further hardening of Cold War positions, symbolized by his endorsement of high defence budgets and the ‘Star Wars’ anti-missile system. Yet the Soviet selection in 1985 of a moderate and innovative Communist Party secretary, Mikhail Gorbachev, and growing Russian economic problems, rapidly changed the very nature of the Cold War. Within two years the two superpowers reached the first of several agreements to reduce nuclear weapons, and in 1989 Gorbachev withdrew Soviet troops from Afghanistan. That same year the Warsaw Pact collapsed as he permitted non-Communist governments to assume power in the Soviet satellites in Eastern Europe. In October 1990 the two Germanies were reunited, and the next month the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe declared the end of the Cold War. A year later, in December 1991, the Soviet Union itself dissolved, to become the short-lived Commonwealth of Independent States.

As John Lewis Gaddis pointed out in We Now Know (1997), until the 1990s a Cold War historian inescapably wrote from the perspective of one living in the era under discussion, a viewpoint which tended – and the pervasive memories of which sometimes still tend – to make detached analysis somewhat difficult to attain. Moreover, until Soviet, Eastern European, and even some Chinese archives began to open in the 1990s, historians enjoyed access – and even that partial – only to Western sources on the Cold War, making any discussion of the preoccupations, mindset, motivation, and policies of Communist bloc countries and leaders largely speculative. Even now, much material from both sides of the divide remains closed, and a definitive history of the Cold War will not appear for decades, if ever. Yet, such caveats notwithstanding, in the year 2000 we can at least begin to escape from the often overly simplistic and even propagandist analyses which marred much writing on the Cold War and look back at the period Richard Crockatt has termed the ‘fifty years’ war’ with a new understanding of the complexities and ambiguities which almost certainly characterized its emergence, development and impact.

![]()

ONE

The European Dimension, 1945–1950

Historians have argued over almost every aspect of the Cold War, including the precise date it began. Some trace its origins as early as 1918, shortly after Bolshevik revolutionaries led by Vladimir Ilyich Lenin established a Communist government in Russia. The United States joined Britain, France, and Japan in sending troops to Siberia, forces whose stated objective was merely to keep the trans-Siberian railway line open and protect Allied supplies near Vladivostock against German seizure. In practice America’s partners quickly expanded this undertaking, which lasted until spring 1920, into attempts to overthrow Communist rule in Russia. Until 1933 the United States, unlike other Western powers, refused to recognize the Soviet government. Even after recognition Soviet–American relations remained cool throughout the 1930s, though despite the purges which the dictatorial Soviet leader Josef Stalin initiated, many leftist Western intellectuals and romantic idealists believed Soviet Communism offered a political model superior to that enjoyed by their own countries. Most Americans, by contrast, feared and deplored Soviet Communism, considering it the complete antithesis of the American free enterprise system, destructive of those individual rights to ‘life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness’ enshrined in the Declaration of Independence, and irreligious to boot.

Despite pronounced Soviet–American ideological antagonism and predominantly cool relations between the two powers, it took a major war to bring their interests into outright collision. During the 1930s the bellicose behaviour and territorial demands of increasingly restive Germany and Italy led Western powers and the Soviet Union to adopt different strategies for dealing with the Fascist powers. Great Britain, France, and even the United States initially acquiesced in the expansionist policies of the German Führer, Adolf Hitler, symbolized by the September 1938 Munich agreement, which ceded much of Czechoslovakia to Germany. This gave way in 1939 to a determination to rearm and make no further concessions. Stalin, by contrast, was apprehensive that, should the German Reich attack Soviet territory, Western powers would leave Russia to face Fascist Germany unassisted. In August 1939 he concluded a Non-Aggression Pact with Hitler, which safeguarded the Eastern German frontier against Soviet attack. In a compact recalling the eighteenth-century partitions of Poland, the two signatories also agreed to collaborate in invading that state, whose territory separated them, and dividing it between themselves. The Non-Aggression Pact effectively freed Germany to begin the Second World War, counting the Soviet Union, supposedly a sworn ideological opponent, as a friendly neutral or even a tacit confederate, which until 1941 provided Germany with substantial amounts of war supplies.

The wartime alliance between the United States, Britain, and the Soviet Union was based decidedly on convenience, not mutual trust. In June 1941 Hitler, having subdued most of Western Europe, including France, the Low Countries, and Scandinavia, in the blitzkrieg launched in spring 1940, chose to invade the Soviet Union. Following the time-hallowed principle that the enemy of my enemy is my friend, Britain and the United States, by this time virtual de facto allies against Hitler even though the Americans had yet to declare war, immediately embraced Stalin as a fellow victim of Hitler. Winston Churchill, the dogged British wartime prime minister, characteristically remarked: ‘If Hitler invaded Hell he would at least make a favourable reference to the Devil!’ Russia immediately joined the beneficiaries of the new Lend-Lease programme, under which the United States was already sending war supplies in bulk to other opponents of Hitler and Japan. After the Pearl Harbor attack of December 1941, when both Germany and Japan declared war on the United States, the ‘big three’ powers were formally allied against Hitler.

Serious strains afflicted their relationship. Although official propaganda portrayed the three allies as sharing common objectives, sedulously glossing over the substantial ideological and practical differences separating their political systems, within each country many officials remained decidedly wary of their supposed confrères. Until 1945 Stalin regularly suspected that Britain and France might make a separate peace, abandoning him to face the might of Hitler unassisted. Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt, the wartime American president, were similarly apprehensive that the Soviet Union might individually negotiate peace with Germany. In the Atlantic Charter both signed in August 1941, Churchill and Roosevelt committed their countries to war aims which included the famous ‘Four Freedoms’, the rights of nations to self-determination and to internal political, economic, and religious freedom, but Stalin declined their invitations to endorse these objectives. Initially Stalin hoped his Anglo–American allies would open a second front in France in 1942, thus relieving the pressure on the Soviet forces and populace who faced the German military unaided. The decision to defer this invasion, first to 1943 and then to 1944, caused him to believe with some justification that his allies had chosen to expend Russian lives to win the war. Soviet wartime losses amounted to at least 20 million dead, as well as enormous devastation to property and industrial plant, since over the three years 1941 to 1944 the Soviet war zone absorbed at least three-quarters of the effort of the German military machine.

Anglo–American strategic decisions to postpone the West European invasion to June 1944 carried important implications for postwar Europe. At the Teheran conference, held in late 1943, the Allied leaders decided that Soviet troops would be left to defeat the German occupying forces – or in Rumania and Hungary, allied forces which controlled most East European countries, including Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Rumania, Bulgaria, and Albania, states which by early 1945 were under de facto Soviet control. As Soviet military conquest reached into Eastern Germany, Stalin considered the extension of Soviet power to Eastern Europ...