![]()

1

Your Very Own Eric

It was almost midnight in Factory Road. Everyone in the tiny two-up, two-down terraced house was in bed except for Eric Harden. He was poring over a letter to the girl who had come to mean everything to him. But, as usual, he was fumbling around for the words to match his feelings. They’d been going steady for three years. They had been the best three years of his life, and it was all down to her. But how to get it across? He knew he was no wordsmith, but there were times when he felt that his letters made no sense at all. Once, in exasperation at his own incoherence, he had scribbled: ‘I’ll bet you read them two or three times before you know what I have written and then I’ll bet sometimes you give it up as a bad job.’1 That hadn’t stopped him trying, however. If anyone could understand what he was trying to say, or could read the true meaning behind the awkward lines, it was surely his darling Maud. She knew him better than anyone. So, fondly recalling his last trip to see her, he wrote clumsily:

I must thank you very, very much for looking after me, and, please dearest, keep it up if you can, no matter what I say or do because whatever it is that I say or do I don’t mean any of it really. You are a darling to me and, gee, I love you for it. I hope you get this letter alright, dear, because I will have to wait until tomorrow to post it because I haven’t a stamp. That’s just like me, isn’t it. I wonder you don’t get fed up with me what with one thing and another. You have a lot to put up with from me don’t you dear?2

Before turning out the light and heading up to bed, he closed the letter, as he always did, with three kisses from ‘Your Very Own Eric’.

Romance and Factory Road. It wasn’t something you would normally associate with the uninspiring and singularly unremarkable red-brick terraced street that branched off like a rib from the spinal column of Northfleet’s flourishing High Street. There was nothing at all romantic about Factory Road. No ornament. No architectural flourishes. It was humble, plain and utilitarian, a working-class street in a workaday town. A century or more earlier it had been very different. Upper Northfleet, as it was known then, was a Kentish pastoral haven noted for its yields of watercress and fruit. It was a place of cherry orchards and grand houses where green and pleasant parklands rolled down to meet the Thames Estuary. Once upon a time, it was the very evocation of ‘the garden of England’, but not any more. The pastures where mansions like The Hive once stood in splendid isolation were now a hive of industry and pinched terraces dominated by soaring chimney stacks that belched smoke into a smog-clouded sky. The invention of Portland cement had transformed Upper Northfleet’s fortunes along with its rural appearance. With its bountiful chalk hills and its proximity to the Thames, the village was ideally situated, not only for the production of cement but for its easy transportation. So the great houses were demolished and the fields and orchards were despoiled with chalk workings to fill the ravenous maw of cement manufacture.

By the 1930s, William Aspdin’s experimental enterprise had expanded into the noisy, vast and perpetually dust-shrouded Bevan’s Works, one of the largest and most productive cement factories in Europe, with a yearly output of nearly half a million tons. Recognising the strategic value of the town’s Thames-side location, more factories took root along the river. Chief among them was the new Northfleet paper mill, Bowater’s, which kept the national press supplied with newsprint, and Henley’s Cable and Telegraph Works. With industry came jobs and an explosion in house building. A web of streets linking the chalk-rich, riverside escarpment to the new High Street provided homes for hundreds of factory workers and their families. In this way, Upper Northfleet became the thriving heart of a conjoined Northfleet with its own cinema, community hall, playing fields, school and swimming pool.

It was a close-knit community. Bert Chapman, whose family lived next door to the Hardens in Factory Road, likened life in the terrace to Coronation Street. ‘Everybody knew everybody,’ he said.3 Children played in the streets or roamed the disused and overgrown chalk workings. Known as The Main, this area was a childhood paradise where youngsters ‘could climb trees, swing on ropes and build camps and dens and generally have a great time in their own little world of adventures’.4

This was the world that Eric Harden grew up in, the world in which he lived and worked. It was the only world he had ever known.

He was born just a few doors away, in the same unimaginatively styled Factory Road, on 23 February 1912, as Captain Scott’s ill-starred party were plodding to their doom across the South Polar icecap. The third son and seventh child to William (Bill) Thomas Harden and his wife, Fanny Maria (née Seager), he was christened Henry Eric, although he never used his first name, which he hated. Young Eric, with his green eyes and shock of curly brown hair, joined an already crowded household that would be swollen three years later by the addition of an eighth and final child. Hilda (b. 1915) joined Ethel (b. 1895), Ann (b. 1897), Bill (b. 1901), Joe (b. 1903), Mabel (b. 1905), Maude (b. 1909)5 and Eric at number 44. Conditions were cramped. Downstairs consisted of a small living room and a larger but rarely used ‘parlour’ that housed the family piano and looked out onto the street. In common with most such terraces at that time, there was no bathroom, just an outdoor toilet with a tiny scullery tacked onto the back of the house. Beyond a curtain in the living room, a narrow staircase led up to the two bedrooms, which were unevenly shared: the three brothers and father in one and five sisters and mother in the other. It was a tight squeeze, which must have strained the family harmony, not to mention the family budget, to the limit.

Though not poor by the standard of the times, the family was far from being comfortably off. Eric’s father made a living on the barges that traded along the Thames and Medway. As such, he was following in a long family tradition of river work. Oliver Smith had his own barge in the nineteenth century and his daughter married into the family of David Harden, who was described as a shipwright. Bill Harden learned his trade aboard his father’s barge and progressed to become skipper of his own craft, ferrying cargoes, mainly of bricks, into London. Unfortunately, his boat-handling skills were matched by his fondness for the ‘demon’ drink. It proved to be his downfall. According to family legend, he lost his captain’s licence after being caught drunk in charge of his barge. It didn’t stop him working on the boats, but it did significantly reduce his income.6

As soon as he was old enough, Eric followed his siblings to Lawn Road School, otherwise known as Northfleet Primary School. Just round the corner from Factory Road, when it was opened in 1886 it was the first board school to be built in the town and was distinguished by a grand clock tower that was added seven years later. Eric’s own school career was less spectacular. A solid rather than remarkable student, his boyhood interests lay elsewhere: in music, sport and all manner of outdoor pursuits.

The Hardens were a musical family. Eric was a gifted violinist and his brother Joe played the banjo. As well as performing, usually at family gatherings, Eric was also an enthusiastic concertgoer. He grew to love classical as well as popular music and his favourite work was said to be Mendelssohn’s ‘Violin Concerto’. The advent of the wireless was a boon that allowed him to expand his musical knowledge and over time he acquired his own collection of records that he enjoyed playing. His passion for music stayed with him for the rest of his life and during his subsequent wartime army postings he would seize any opportunity to attend concerts or shows.

Eric’s other abiding passion was keeping fit. Of medium height, slim and with an athletically built, he was an enthusiastic cricketer, footballer and tennis player. He even tried his hand at bodybuilding, until an accident with his chest expander resulted in him consigning the contraption to a drawer, never to be seen again! But his greatest and most enduring love was swimming. His eldest sister, Ethel, had been a champion swimmer as a schoolgirl and a talent for water sports clearly ran through the family, encouraged by Bill Harden senior, who had his own somewhat unorthodox teaching methods. Eric’s niece, Josie Haynes (née Harden), recalled:

There was a swimming pool in Gravesend and a little one in Northfleet, but Eric and my father [Joe] learned to swim in the Thames. Their father used to take them out on his barge. He would put them into a cradle that was strapped to the side of the barge and he’d lower them over the side and dangle them in the water, so that they learned to swim that way. The Thames was a lot cleaner then. People used to swim in the river a lot in those days. And it certainly worked for them. They both became very good swimmers, just like aunty Ethel.7

By the mid-1920s, however, Eric’s focus was less on recreation and more on work. Having left school, he might have been expected to follow his father and other generations of Hardens onto the Thames, or, at least, into the closed-shop world of the docks where his eldest brother Bill worked. His father, who held a prized stevedore’s ticket, offered one to Eric, just as he did to Joe, but both turned the offer down. Instead, Eric chose to work for his sister Ethel’s husband in the High Street butcher’s shop that he owned. Fred Treadwell was a notable figure in Northfleet business circles. A self-made man, he had started out as a butcher’s boy before buying out his original employers the year Eric was born. After serving as an artilleryman during the First World War, he re-opened his shop and, despite suffering the legacy of gas poisoning, turned it into one of the most successful butcher’s in Northfleet. As a Freemason and leading member of the local master butchers’ association, Fred was well liked and well connected. In spite of the age gap between them – Fred was more than twenty years older than Eric – they got on well together, sharing a mutual interest in the fortunes of Northfleet Football Club for whom Fred had played before becoming a vice-president.

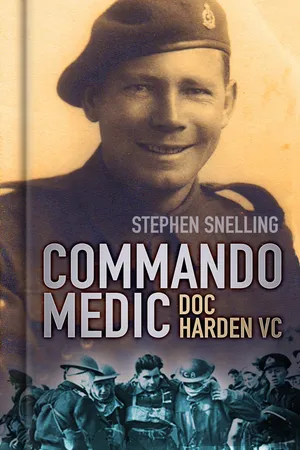

Happy days at Dymchurch. Young Eric (centre) displays his athleticism with a group of friends, c. 1935. Maud is on the left. (J. Wells)

Yet, for all his close family ties, Eric was not given an easy ride. He started out, just as Fred had done, as butcher’s boy, labouring in the shop and the slaughterhouse at the back and delivering orders of meat to customers all around the town. His rounds, originally covered on a bicycle and later in a van, made him a familiar figure around Northfleet’s fast-expanding housing estates. With his boyish good looks and cheery charm, he brought to the job all the high-spirited exuberance of youth. Among his regular customers were members of his family, and his niece Josie recalled watching at the window with her brother John for the arrival of their favourite uncle:

We were very fond of him. He was always full of life and used to run and dash about. He was very fit and agile. We were living in a flat over Halls’ paper shop in Rosherville and he used to call out and come running upstairs. Mum always had a cup of tea ready for him…8

Sometimes, his enthusiasm and desire to do everything at breakneck speed landed him in trouble, as Josie remembered:

He liked to drive fast. I remember he helpe...