![]()

FOUR

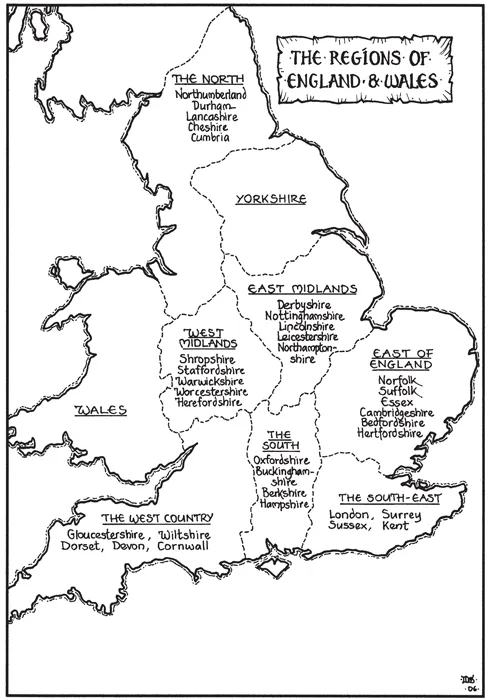

THE GUIDE BY REGION

VISITING THE SITES

• It is better to go in summer – houses and castles are often closed to the public in winter. Even churches are more likely to be open in the summer months.

• Afternoons are best, until 4.30 p.m.

• Access to churches can be difficult, even in summer, because of problems of theft and vandalism. Parish churches in urban or semi-urban environments are often likely to be locked. Churches in very isolated rural environments may also be locked. Cathedrals and large town churches are usually open with supervision. A phone call or letter before your visit is the best idea. Alternatively, a phone number is usually given on the board in the churchyard or in the church porch, or a key is sometimes available locally.

• Phoning clergy and parish offices in the morning is better.

• Church brasses are often under carpets.

• Most cathedrals ask for visitors’ donations.

• All of the sites in this guide are open to the public.

• Directions are given to each site, and are designed for use with modern motoring atlases. Where there is more than one church in a town (tower) or (spire) is indicated.

RATING SYSTEM FOR SITES

| * | Standard monument. Person involved in battle or royal official. |

| ** | More detail known of involvement or some architectural interest. |

| *** | A significant participant in the Wars. |

| **** | Outstanding historical interest. |

| ***** | Truly national importance. |

RATING SYSTEM FOR BATTLEFIELDS

+ | Site known but little survives. |

++ | Site known and some interesting survivals. |

+++ | Plenty to see or key battle with some survivals. |

++++ | Key battle with much to see. |

+++++ | Decisive battles with plenty to see. |

POUND SYMBOL

£ | Entrance fee charged. |

££ | Higher entrance fee charged. |

ABBREVIATIONS

NT | National Trust property |

EH | English Heritage property |

Cadw | Welsh Historic Monuments |

KAL | Key to church available locally (check porch/board) |

PO | Parish office phone number |

UNDERLINING

Underlining is used to highlight the person(s) involved in the Wars of the Roses who is being celebrated at a particular site.

BOLD TYPE

Bold type is used in site descriptions in three ways:

1. To highlight locations in a building, e.g. chancel.

2. To indicate a secondary site, e.g. Pickworth.

3. To highlight a memorial at a site to a person who features in Chapter 3, ‘Main Protagonists’, where biographical information is given, e.g. Lady Margaret Beaufort.

SITE CATEGORIES

Sites are split into primary sites (220) and secondary sites (40). Secondary sites are conveniently close to primary sites but do not necessarily warrant a long-distance visit on their own merit. They are ‘whilst you are in the area do also visit’ sites. Full directions are not necessarily given for secondary sites.

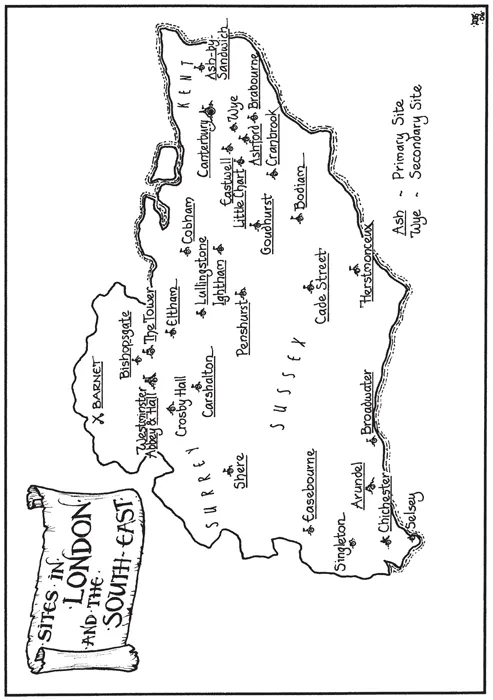

LONDON AND THE SOUTH EAST

ARUNDEL, Castle *** ££

Close to the town centre, the Fitzalan Chapel of St Nicholas Church contains a fine collection of Fitzalan and Howard monuments. Note that the chapel can now only be reached from the castle grounds.

Our interest is in the superb chantry-tombs of William Fitzalan, 9th Earl and his son Thomas, 10th Earl in the Fitzalan Chapel.

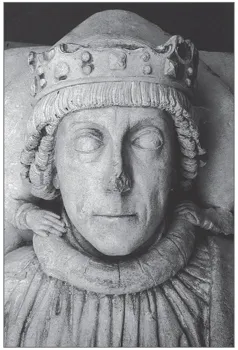

William Fitzalan (1418–88) married Joan Neville, the Kingmaker’s sister, and thus became Edward IV’s and Richard III’s cousin by marriage. He fought in the French wars and was involved in suppressing Cade’s Rebellion in 1450. He had early Yorkist sympathies in the 1450s but may have been present at the rout of Ludford Bridge (1459) on the Lancastrian side. He fought for the Yorkists at the Second Battle of St Albans (1461) and, probably, Losecote Field (1470). He became a member of Edward IV’s close circle, accompanying him to George Neville’s lodgings in 1467 to recover the Great Seal – an event of great political significance at the time, as it signified Edward’s break with the Nevilles. Arundel also was in the party that accompanied Edward in October 1469 on his re-entry into London following his release from captivity by Warwick. Arundel was involved in suppressing the Fauconberg risings of May 1471 and was Constable of Dover Castle and Warden of the Cinque Ports. He appears to have supported Richard III in October 1483 but not to have been involved, probably owing to old age. Although they were thoroughly involved in the Wars the Fitzalans do not seem to have really ‘punched their weight’.

Effigy of William Fitzalan, 9th Earl of Arundel in the Fitzalan Chapel, Arundel Castle.

Thomas Fitzalan (earl from 1488, died 1524) married Margaret Woodville (Queen Elizabeth’s sister) in 1464. He was created Lord Maltravers in the 1460s by Edward IV, and Knight of the Bath at Elizabeth’s coronation. He supported Richard III during his reign and patrolled the Channel on his behalf. He fought for him at Bosworth. Thomas lived and died at Downley Park hunting lodge, Singleton. Two empty tombs can still be seen in Singleton parish church – one for Thomas and one for his son, also Thomas, 11th Earl. Both were probably buried in Singleton to start with and moved to Arundel at the end of the sixteenth century when the Singleton lands were lost to the earldom.

ASH-BY-SANDWICH, St Nicholas Church **

2 miles west of Sandwich, in village centre now bypassed by A257.

In the chancel are alabaster effigies on a tomb-chest of John de Septvans (d. 1458) and his widow, Katherine. Round his neck is the ‘SS’ collar of the House of Lancaster. He was pardoned for taking part in Jack Cade’s Rebellion in 1450 against Henry VI’s government, one of a substantial number of wealthy people involved in that dangerous uprising. (See Cade Street.)

ASHFORD (Kent), St Mary’s Church ***

Town centre, within pedestrian precinct (tower).

In the chancel are a tomb-chest with brass (only the head remains) and the tilting helmet of Sir John Fogge (c. 1418–90). Sir John is one of the very few people to have been involved throughout the Wars. He is said to have served Henry VI and helped put down Jack Cade’s Revolt of 1450. However, along with Sir John Scott, he threw open the gates of Canterbury to the Calais earls (March, Salisbury and Warwick) in July 1460 and joined the Yorkists. He fought at the battles of Northampton, Second St Albans and Towton. He married Alice Haute, a cousin of Elizabeth Woodville and related to Sir Richard Haute, and was a hunting companion of Edward IV in the mid-1460s.

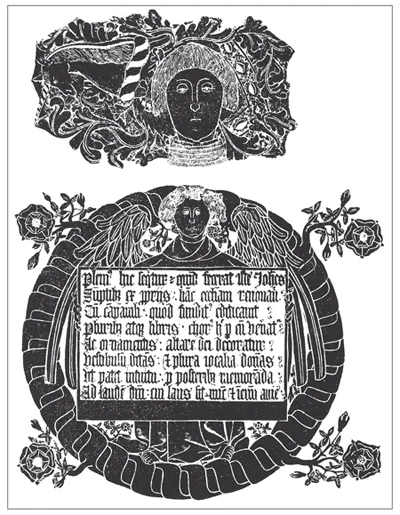

Monumental brass remains and inscription from the tomb-chest of Sir John Fogge in Ashford church.

Fogge became a prominent courtier under Edward as King’s Knight and Treasurer of the King’s Household 1461–7, as well as administrator of the Duchy of Lancaster for the Prince of Wales, later Edward V. He was specifically named in Warwick’s and Clarence’s manifesto for their 1469 rebellion against Edward IV as one of the ‘persons giving covetous rule and guiding’ to the King. In the summer of 1471 he was involved in the subjugation of the last pockets of resistance following the Bastard of Fauconberg’s revolt. Fogge was prominent in the Kent risings during Buckingham’s Revolt in October 1483, having been absent from Richard III’s coronation. He was attainted for his part in it but then surprisingly pardoned by Richard. Sir John helped rebuild this church, including building the existing tower between 1470 and 1490.

THE BATTLE OF BARNET (14 April 1471) +++

Strategic Background and the Campaign

Relations between Edward IV and Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick (the ‘Kingmaker’) deteriorated steadily through the late 1460s. Warwick was driven to rebellion with Edward’s brother George, Duke of Clarence in both 1469 and 1470, both ultimately unsuccessful. After the Lincolnshire rebels’ defeat at the Battle of Losecote Field (12 March 1470) Warwick realised he was never going to succeed in placing Clarence on the throne of England. By April, Warwick and Clarence were forced into exile in France. Here Warwick immediately declared for Henry VI and enlisted the help of King Louis XI of France to reinstate Henry to the throne of England. A reconciliation of sorts with Queen Margaret was achieved (although she kept Warwick on his knees for a full fifteen minutes before the interview) and Warwick’s younger daughter Anne Neville was betrothed to Henry’s son, Prince Edward, now nearly 17 years old. By early September 1470, Warwick was ready. His invasion fleet landed near Exeter and Warwick was able to regain entry to London unopposed on 6 October, because Edward had been lured to the north by rebellion and then suddenly and treacherously abandoned at Doncaster by his long-standing supporter John Neville, Marquis Montagu (Warwick’s brother). Potentially caught between two ‘rebel’ armies, Edward chose flight to King’s Lynn with just a few companions, including Richard of Gloucester, his brother and Lord Hastings, and on 2 October departed by ship to the Low Countries and the protection of his brother-in-law, Duke Charles of Burgundy. The Readeption of Henry VI, with Warwick again in power, had begun (Queen Margaret and Prince Edward remained behind in France until England was fully safe).

By early March, Edward was to ready to return to England to reclaim the throne he had so dramatically vacated. A fleet of thirty-six ships containing Burgundian mercenaries set sail on 2 March from Flushing harbour. An abortive attempt was made to land at Cromer in Norfolk, but the area was too well guarded by Lancastrians. The fleet continued up the east coast but was hit by storms and scattered. Eventually the ships reunited at Ravenspur (near Spurn Point), at the mouth of the Humber. Edward bluffed his way through traditionally Lancastrian country by claiming he was coming to regain only his dukedom of York ...