- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Coxinga and the Fall of the Ming Dynasty

About this book

This is the fantastic true story of the infamous pirate; Coxinga who became king of Taiwan and was made a god - twice.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Coxinga and the Fall of the Ming Dynasty by Jonathan Clements in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE PIRATES OF FUJIAN

Cut off from the rest of China by a semicircle of high mountains, the south-eastern province of Fujian was almost a separate nation. The slopes that pointed towards the sea were carved into terraces, where the locals grew native produce like lychees and longans (‘dragon’s eyes’), tea and sugar-cane. Cash crops were the order of the day, and not merely for sale as exotic foodstuffs. The Fujianese grew flax for the manufacture of cloth, and mulberry trees for feeding silkworms. They were particularly renowned for their dyed silks, and locally grown indigo plants formed the basis for Fujian blue, while safflowers were harvested to make a multitude of reds. With textiles and a growing porcelain industry, the Fujianese were bound to seek trading opportunities, and the province’s walled-off existence afforded a unique possibility. The populace huddled in bays and estuaries, from which the easiest mode of transportation was by ship. The Fujianese became accomplished fishermen, and inevitably found other uses for their boats.

By command of the Emperor, China had no need for foreign trade. China was the centre of the world, and it was heresy to suggest that any of the barbarian nations had anything of value to offer the Celestial Empire. Occasional parties of foreigners were admitted to bear ‘tribute’, arriving in China with fleets of goods, which would be graciously exchanged between government agents for treasures of equivalent value, but it was a cumbersome way of doing business, and, by its very nature, excluded private entrepreneurs.

Two hundred years earlier, in the heyday of the Ming dynasty, the mariner Zheng He had sailed across the Indian Ocean in a fleet of massive vessels, returning from distant lands with bizarre beasts and stories. He also bore ‘tribute’, assuring the Emperor that barbarians as far away as Africa had acknowledged him as the ruler of the world. However, after Zheng’s famous voyages, the Ming dynasty retreated into self-absorption once more, confident that there was little in the wider world worth seeing.

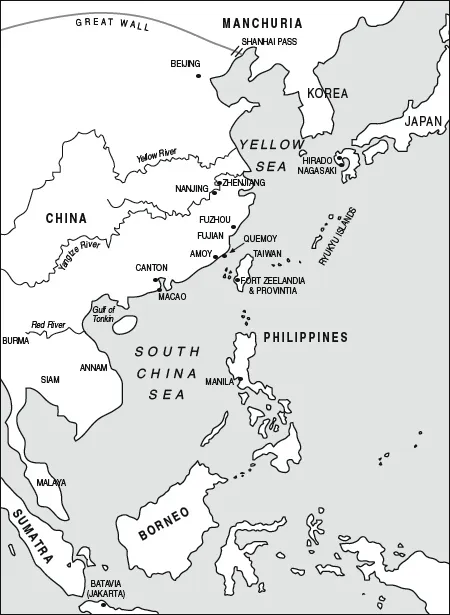

East Asia in the seventeenth century.

Iquan, the future Lord of the Straits, was born in 1603 in the small Fujianese village of Nan-an, near Amoy. The place had only two relatively minor claims to fame. The first was a strange rock formation at a nearby river-mouth, said by the locals to represent five horses – four galloping out to sea, while a fifth shied away, back towards land. Later writers would interpret this as referring to Iquan, his son Coxinga, his grandson Jing and two of his great-grandchildren, Kecang and Keshuang.

The second famous place in Nan-an was a rock, shaped like a crane, which bore an inscription by a philosopher of a bygone age who had been posted to the region as a civil servant. He had announced, to the locals’ great surprise, that the area would one day be the birthplace of ‘the Master of the Seas’. The same site was visited centuries later by the founder of the Ming dynasty, who was aghast at the powerful feng shui. He announced that the region risked becoming the birthplace of an Emperor, and ordered that the stone inscription should be altered. This act, it was later said, is what kept Iquan’s family from becoming the true rulers of all China.1

Iquan shared his surname, Zheng (‘Serious’), with the famous mariner of times gone by, but this was merely a coincidence. The historical Admiral Zheng was a eunuch and a Muslim from China’s interior, whereas Iquan hailed from a clan that had lived in coastal Fujian for generations. His father was Zheng Shaozu, a minor official in local government, while his mother was a lady of the Huang trading family.2 Shaozu seemed determined to bring respectability to his family, and encouraged his children in China’s most acceptable way of advancement. He was wealthy enough to afford a good education for his sons, and hoped that they would find success in the civil service examinations: the only way of achieving office in the Chinese government. Shaozu’s ambitions for his family were not uncommon, and Fujian province was a hotbed of academic endeavour – it sent more graduates into the civil service than any other province in China. However, Shaozu’s sons were to bring him an endless series of disappointments, and he did not live to see the incredible achievements of their later life. In the case of his eldest son Iquan,3 it was undeniable that the meek, conservative genes of the Zheng strain had lost out to the wild-card heritage of the Lady Huang, whose family, it was later discovered, were a group of reprobates involved in questionable maritime enterprises.

Iquan had many names in the course of his life, but was known at home simply as ‘Eldest Son’. As is common with some Chinese families even today, he and his brothers also concocted a series of semi-official nicknames. In the case of the Zheng boys, they named each other after imagined animal attributes. As the eldest, Iquan seized Dragon for himself – the noblest of Chinese beasts and the symbol of imperial authority. The next eldest brothers grabbed the next-best names – Bao the Panther, Feng the Phoenix and Hu the Tiger. An avian theme among the younger brothers implied they were the sons of a different mother, with names including Peng the Roc, Hú the Swan and Guan the Stork.

The chief source for the youth of Iquan is the Taiwan Waizhi or Historical Novel of Taiwan, a late seventeenth-century account of the pirate kings that mixes verifiable historical facts with fantastically unlikely tales of their deeds and accomplishments. As seems traditional for all Chinese books on figures who would later find fame, it begins by describing Iquan in familiarly glorious terms that would please any Confucian scrutineer. According to the Historical Novel, he was able to read and write by age seven, a not inconsiderable feat, and displayed a great aptitude for dancing and other forms of the arts. Before long, however, the Historical Novel slips from empty platitudes of child prodigy, and into accounts of events more in keeping with Iquan’s later life.

His most distinctive characteristic, evident even in his childhood, was his rakish charm, which often allowed him to get away with mischief. The first story of Iquan’s remarkable life takes place somewhere around 1610, when the boy was playing with his younger brother Bao the Panther in the street near the house of the local mayor Cai Shanzhi. Close within the walls of Cai’s gardens, the boys could see a lychee tree – the luscious fruits were native to Fujian, and highly prized. They tried to knock some of the ripe lychees down by throwing sticks into the branches, and, when the local supply of sticks was exhausted, tried using stones instead. Unfortunately for Iquan, one of his well-aimed rocks sailed past the tree and into the garden, where the unsuspecting mayor was sunning himself. It hit him on the head, causing him to fly into a rage and summon both Iquan and his father for disciplinary action.

However, the story goes that Cai’s anger immediately abated ‘when he saw the lovely child’, and instead of venting his anger he allowed the boy to go without punishment, announcing to the world that the future had great things in store for him.4

It is unlikely that Iquan’s father would have agreed, since he saw the boy as a nuisance. Iquan’s mother was not Shaozu’s principal wife, but merely a concubine, making Iquan little more than another troublesome mouth to feed. With at least six brothers and halfbrothers, it is highly likely that Iquan had a similar number of female siblings, though these remain unrecorded in chronicles about his life. Father and son fell out when Iquan’s mother’s looks began to fade, and her patron tired of her, but their chief causes for argument were mainly Iquan’s doing. In such a precarious family position, it would have been smart to avoid drawing unwelcome attention to oneself, and yet the teenage Iquan seemed to covet danger. As his boyhood high spirits gave way to surly adolescence, Iquan made a show of disobeying his father’s advice, and neglected his obvious academic potential. He was also caught in bed with his own stepmother, which was the final straw. Strictly speaking, Iquan had committed a capital offence and hastily left his home town for Macao, where, his father imagined, he was bound to come to a bad end.5

To most Chinese, Macao might as well have been a whole world away, several hundred miles down the Chinese coast, at the very edge of civilisation. South of Macao, there was nothing but the sweeping curve of what is now Vietnam, a land of questionable provenance in the eyes of the snobbish Chinese. Beyond that lay Malaya and the Indonesian Spice Islands – lands of opportunity, but also of savagery and danger. Conveniently positioned for trade at the mouth of the Pearl river estuary, Macao was originally founded as a trading post by merchants from Iquan’s native Fujian.

It was named after A-Ma-Gong, or Matsu, the sea goddess worshipped by all local sailors. Matsu had once been a mortal, a Fujianese virgin who had been able to leave her sleeping body in phantom form to rescue troubled sailors. After her death, sightings of her ghost were often reported in coastal communities, and sailors continued to make sacrifices to her in the hope of safe journeys.6 Reputedly, some of these offerings were even human sacrifices.

Macao’s new occupants, the Catholic Portuguese, were deeply suspicious of such foreign cults and renamed the city in praise of a more acceptable divine virgin, calling it the ‘City of the Mother of God’. The town was a vital point on the unofficial trade routes in and out of China, only a few miles from the Pearl river delta and the great city of Canton. This location made Macao a place of vital strategic importance, and it would remain so for two more centuries until the nearby village of Hong Kong fell into the hands of the British and superseded it.

The Portuguese had gained a toehold in Macao by clearing the Pearl river estuary of pirates, but their presence at the edge of the Celestial Empire was barely tolerated. They were still not permitted entry into China proper, but the city was home to many traders and missionaries who hoped the strict laws would be lifted. While they waited, they did their best to interest the local Chinese in their cargoes and their religion.

Accompanied by his brothers Bao the Panther and Hu the Tiger, who were probably as much of a handful as he was, the teenage Iquan arrived in Macao at the house of his grandfather Huang Cheng, who was a merchant in the city. The Historical Novel describes ‘a youth eighteen years of age, lazy by nature with no taste for learning; strong-armed, fond of boxing and martial arts. He secretly went to [Macao] in Canton, and visited Huang Cheng, his mother’s father.’7 Considering the recent upheavals back home in Fujian, it is possible that the boys arrived in the company of Lady Huang herself, returning to her family home after her fall from favour.

Life in Macao would have been a great surprise to Iquan, particularly after the stuffy environment of his father’s house. The Huangs were just as keen on advancement and success, but rated material wealth over academic accolades – they were merchants and traders, and Iquan found his natural talents were far better suited to business than study. Business was good for the Huangs, but that did not mean that business was always legal.

Iquan was destined to discover south China’s not-so-secret vice – communication with the outside world. The later emperors preferred to cower behind the natural and man-made barriers that kept the barbarians at bay, but their influence was not allencompassing, even within their own borders. A government report of the time noted that Fujian was a place where ‘cunning bullies can carry out their crafty schemes’. Thanks to the many inlets and secluded harbours along the coast, private traders could flourish, out of the sight of the tax inspector.8

Chinese sailors were permitted to leave port to fish or move goods along the coast to the next local port, but their seaward ventures were supposed to stop there. Supposedly, no Chinese vessel carried more than two days’ fresh water for its crew9 – a rule which should have confined all shipping to the coastline, within reach of resupply. However, the fishermen of Fujian knew what was beyond the horizon. They were, after all, the descendants of the voyagers who had sailed distant oceans in the company of the eunuch mariner Zheng He, and the local city of Quanzhou was still the designated port for receiving embassies from the tributary nation of the Ryukyu Islands. Unlike their landlocked brethren of the hinterland, they saw the sea on a daily basis, and did not fear it.

Chinese vessels could hug a coastline, but were hardly suitable for ocean-going travel. However, as one of the few points on the Chinese coast with a tradition of dealing with foreign places, Fujianese shipwrights knew how to build vessels that could sail to other lands. But these ships were expensive, over ten times the cost of mundane vessels – less wealthy local entrepreneurs found other ways to rig their ships for longer voyages. Within sight of the coast, the Fujianese vessels were flat-bottomed affairs that sat low in the water – only a madman would take one out into the open sea. But as soon as the sailors cleared the watchful eyes of the local law enforcement, they would transform their vessels, bolting fences of split bamboo around the bulwarks to stay waves from washing over the deck, and lowering a giant knife-like wooden blade into the water that served as an auxiliary keel to keep the ships stable.10

Putting out to sea from a Fujian village, a local boat could pretend to make along the coast, before running for the east the moment it was out of sight of land. As the shallow coastal shelf fell away, most Chinese sailors recoiled in fear at the sight of the darkening waters below their vessels, telling horror stories about the ‘Black Ditch’ that lay just off the coast. Dangerous currents and savage sea monsters lurked in the fearsome depths, and stories about them were enough to keep many Chinese sailors reliably close to shore.11 But for the sailors of Fujian, there was something beyond the Black Ditch.

From the ports of Fujian, it was less than two days’ sail to the lawless island of Taiwan. The mandatory two-day supplies were sufficient to sustain the crew for a one-way trip out of Chinese waters and into a whole new world. After restocking in Taiwan, it was possible to hop along the Ryukyu island chain, all the way to the Japanese ports of Hirado and Nagasaki. Other merchants preferred to make the seaward leap out towards the Spanishoccupied Philippines, or smaller hops along the coast of Annam (now known as Vietnam), down towards Java, where the Dutch East India Company had made its base.

The people of Fujian had settled in some of these destinations. Chinese merchants and their families (or, in many cases, their local wives and children) formed distinct Chinatown communities in Manila and Nagasaki. Few of them expected to be permanent immigrants, but as it became economical for organisations to keep representatives in foreign ports, the practice of taking on a temporary foreign posting became known as yadong, or ‘hibernation’. Surely no true Chinese could stay for too long away from the Celestial Empire, but there seemed little harm in a short foreign stay, especially if there was profit to be made.

Officially, China had no foreign trade, but decades of illegal commerce had brought many new items, some of which had exerted a great influence on the culture of the time. The chilli, a vital ingredient in Chinese cookery, particularly in spicy Sichuan cuisine and the hot-sour soup of Beijing, was not native to China at all. This exotic plant was brought to the Philippines from South America by the Spanish, and traded there with Chinese merchants – there were no modern chillies in China before the sixteenth century, and yet today it is impossible to imagine Chinese food without them.

Another import from the New World was tobacco, which followed a similar route to China through Spanish hands. During the 1600s, rumours spread through China that the Fujianese had invented a miraculous breathable smoke that made the inhaler drunk. After early popularity with the sailors, the ‘Dry Alcohol’ plant was soon cultivated in the soil of Fujian itself, and merchants began to process it and sell it as a local product. Hundreds of factories sprang up in Fujian and neighbouring Canton, and the vice took off all over the country – it was particularly popular with soldiers, and one authority reported that by 1650, ‘everyone in the armies had started smoking’.12

But these were relatively minor fads compared with the immense impact of yet another import. In a period of great climactic uncertainty, plagued with floods and famines, the Fujianese merchant Chen Zhenlong was greatly impressed by the high-yield, fast-growing sweet potatoes he saw cultivated in the Philippines. He bought some of the exotic American plants and brought them home, growing them experimentally on a plot of private land. When Fujian was struck by a crippling famine in 1594, the canny Chen approached the governor with his new discovery, and persuaded him to introduce it that season. The venture was rewarded with a crop that saved the lives of thousands of Fujianese. The governor gained the nickname ‘Golden Potato’, and the incident led to the composition of He Qiaoyuan’s ‘Ode to the Sweet Potato’, part of which went:

Sweet potato, found in Luzon

Grows all over, trouble-free

Foreign devils love to eat it

Propagates so easily.

Grows all over, trouble-free

Foreign devils love to eat it

Propagates so easily.

We just made a single cutting

Boxed it up and brought it home

Ten years later, Fujian’s saviour

If it dies, just make a clone.

Boxed it up and brought it home

Ten years later, Fujian’s saviour

If it dies, just make a clone.

Take your cutting, then re-plant it

Wait a week and see it grow

This is how we cultivate it

In our homeland, reap and sow.

Wait a week and see it grow

This is how we cultivate it

In our homeland, reap and sow.

In a famine we first grew it

In a Fujian starved and rude

But we gained a bumper harvest

People for a year had food.13

In a Fujian starved and rude

But we gained a bumper harvest

People for a year had food.13

The trade was by no means one-way, and rich rewards awaited those who were prepared to take the risks. A length of Chinese silk could sell in Japan for ten times its domestic price. Iron pots and pans could also fetch a high return if anyone was prepared to run the gauntlet up to the Japanese harbours. Owing to a convenient accident of international diplomacy, the Ryukyu Islands were officially a tributary state to both the emperors of Japan and China. Though both nations supposedly frowned on international private trade, it was difficult to prove that a group of Chinese sailors arriving in Nagasaki weren’t actually Ryukyu Islanders, and therefore locals. Equally, when the same sailors were heading for home, they were Ryukyu Islanders until they reached the coast of China, at which point they miraculously transformed into Fujianese fisherman once more, albeit Fujianese whose hold would often turn out to have suspiciously large amounts of Japanese silver in it.

Inspections, however, were rare. In outlawing almost all foreign trade, the Chinese government had effectively criminalised every Fujianese sailor with an interest in making money. This only forced innocent men into the company of rogues, and led many to set their sights on the richer pickings of still greater criminal activities. Bribery and corruption became rife in Fujianese ports, as local harbour masters were encouraged to look the other way when ‘fishing fleets’ put out to sea with no nets but holds full of silk. The more damaging long-term imp...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue 1644: Brightness Falls

- 1. The Pirates of Fujian

- 2. The Deal with the Devils

- 3. The Master of the Seas

- 4. The Heir of Anhai

- 5. The Treason of Wu Sangui

- 6. The Imperial Namekeeper

- 7. The Allure of Treachery

- 8. The Boiling River Dragon

- 9. The Wall Around the Sea

- 10. The Blood Flag

- 11. The City of Bricks

- 12. The Slices of Death

- 13. A Thousand Autumns

- Appendix I: Notes on Names

- Appendix II: Offices and Appointments

- Appendix III: The Rise of the Manchus

- Family Trees

- Notes

- Sources and Further Reading