![]()

TALE 1

THREE FORMER ROYAL NAVY SEAMEN DISCUSSING THE LOSS OF RUSSION CONVEY PQ17

It was lunchtime on an extremely cold December day. I had climbed out of the freezing cabin of the 80ft jibbed Stothert & Pitt electric crane I had been driving, clambered down its steel rungs, whose cold metal tried to arrest each of my hands on its icy bars, on to the quayside. The ship’s quay gang was clearing the last chests of tea from the landing pitch into the transit shed, from alongside the Clan-Line cargo ship we were discharging, ready to make a quick start when we commenced work after lunch.

The winch drivers, who had been working steam winches at other holds on the ship, and their top-hands, had already gone ashore. The ship’s down-hold gangs were popping up out of the deck booby hatchways one at a time, as slowly as air bubbles rise through a glass of newly poured Drambuie, and just as slowly they made their way to the Port Authority’s canteen, to ‘re-fuel’ on subsidised lunches and relax their tired muscles before they returned to the ship to slog their way through the rest of the day. A journey of hard labour that was to last them till they retired, were injured or died of old age, if they should be so lucky.

Those of us who had less arduous and physically demanding jobs, and were saving up to get married or trying to make ends meet for numerous purposes (such as cost of living expenses, mortgage repayments and family holidays), would gather in the Port of London Authority’s gear shed, which was a sanctuary within the docks. It was a place where we could take our pre-packed sandwiches and get a cheap cup of tea made for us by the gear storekeeper, who acquired the tea from damaged chests taken for repair to the coopers and box-knockers’ workshops in one of the transit sheds. It was the only way the storekeeper could earn an addition income to supplement his paltry weekly wage. In the gear store we would sit by a warm coke-fired combustion stove and snooze our lunch hour away, drugged by the fumes from the coke, or talk or just listen to the tales of the older men, whose lives had been spent either in the service of their king and country, fighting wars in distant lands, or on the high seas as Royal Navy or Merchant Seamen, long before they became wage slaves in the port transport industry.

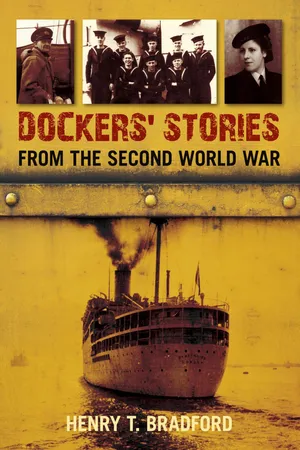

Ship’s crewmen, HMS Collingwood, 1942. Able Seaman Leslie Trott. is second right in the back row. (By kind permission of Mrs Trott)

The tales they discussed between themselves always fascinated me, simply because they were told in that reserved British manner of those days. That is, as though what they had done, the ordeals they had gone through in battles during wars, in countries the world over, the families and comrades they had lost, were all just part of a macabre game. Sometimes, when one of these military or civilian veterans got angry at some offensive remark made by one or other of his contemporaries, he would raise a finger menacingly. Then, on regaining his placidity, he’d smile and clam up; or, if he was incensed or offended by the remark, battle would commence – blood would be spilled.

There was an occasion when three of the men, former Royal Navy deck ratings, were talking between themselves in subdued voices about a convoy they had been escorting to Russia during the Second World War. One of the other dockers, who had been with General Montgomery’s 8th Army in the western desert, butted in on their conversation with some ludicrous remark about the navy, to which he received the ‘stiff finger’ in his treatment, then the smile, then the verbal retort: ‘You should have been there with us on those Arctic convoys. Do you know, once we ran out of butter, and had to do with spreading margarine on our bread. I ask you, margarine.’ That’s the sort of men they were.

What they had been talking about, which was meant to be a discussion between themselves, in low voices that were just above whispers, was the ill-fated Russian convoy PQ17. All three of them had been with convoy PQ17 in July 1942, in cruisers that had been ordered by the First Sea Lord, Sir Dudley Pound, together with all other Royal Navy surface ships, to withdraw from protecting convoy PQ17, because the Admiralty in London had been misinformed that a German pocket battleship had put to sea.

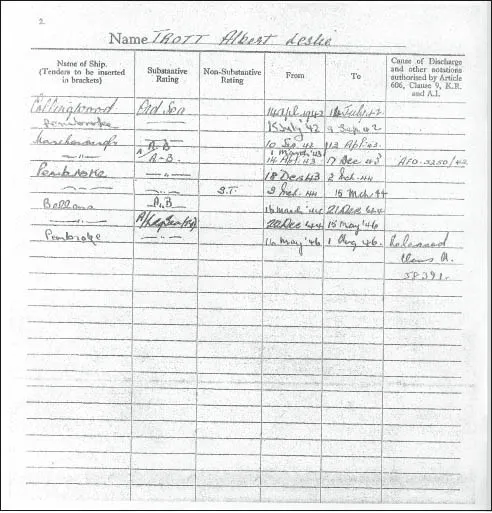

Royal Naval parchment – Record of Service – for Able Seaman Leslie Trott (Author’s collection)

The convoy had then been ordered to disperse, and the merchant ships were to make their own way independently to Russian seaports. The consequence of that order by the Admiralty in London, to abandon convoy PQ17, was that over the next few days of July 1942 German U-boats, E-boats and Luftwaffe aircraft between them sunk twenty-six of those unarmed merchant ships – ships that were carrying hundreds of crated aircraft, tanks, lorries, and tens of thousands of tons of stores and ammunition worth hundreds of millions of pounds, as aid to the Russian war effort.

In the next few days after that order was given, the Germans had been allowed a free hand to destroy the work of many months in British factories, and to take the lives of hundreds of merchant seamen (unarmed civilian non-combatants). It was one of the most disgraceful and dishonourable acts ever perpetrated on one’s own countrymen, by a high-ranking officer of the king’s navy; and to have listened to the former Royal Naval seamen, anyone would have thought it was their decision that caused the catastrophe. All those years after that disastrous event, the shame and guilt of it was still on their consciences, and would be until the day they died.

‘Taking notice of the Admiralty in London showed a real lack of initiative,’ one of them said. ‘The Admiralty order to Commander Brome and Rear-Admiral Hamilton should have been ignored by them.’ Commander Brome and Rear-Admiral Hamilton were the Merchant Navy convoy controller and the naval fleet commanders. ‘Nelson wouldn’t have stood for it,’ one of them said. ‘It would have been the telescope to his blind eye and: “I see no enemy ships, sail on.”’

‘Damn right it would have been,’ replied one of his mates, ‘at least those poor bloody merchant seamen would have had some chance in a protected convoy. Without us they had no chance at all, the poor sots. The senior officers were afraid to use their own initiative; afraid of the consequences if they’d been wrong and gone on protecting the convoy. That was the problem. They’d lost the Nelson touch.’

(See The Guinness Book of Naval Blunders, by Geoffrey Regan.)

![]()

TALE 2

THE ADVENTURES OF TWO JACK TARS IN A BOAT, WITH A WREN

‘Well mates, that naval commander and rear-admiral should have been with me during the war,’ interjected Jack, ‘then they would have learnt what initiative was all about.’

Jack was much older than most of the other men sitting round the combustion stove. He had volunteered for wartime service with the Royal Navy in January 1940, when he was thirty-seven years of age, although you would never have guessed his age. Jack was a Freeman-Waterman-Lighterman of the River Thames. Jack knew every inch of the river and its foreshores, from Teddington Lock to the Nore, the Maplin Sands and beyond. As a boy from the age of twelve (working-class children left school at this age, until the introduction of the Fisher Education Act 1918, an Education Act that established compulsory education in England and Wales for children up to the age of fourteen), Jack started work sailing as the ‘mate’ on Thames barges, sailing craft that plied their trade on the River Thames, round the coast and even across the English Channel to ports in Belgium and France. That experience ended when he was ‘apprenticed’ to his father to become a Freeman-Waterman-Lighterman of the River Thames, where his days were taken up on the river, or in the locks and docks of the Port of London, looking after Thames lighters.

‘How come, Jack? What happened to you?’ he was asked:

Well, it was like this. I hadn’t been in the Royal Navy very long. I’d just finished my initial training, in fact. I’d been detailed to report to Chatham naval barracks. It was mid-May 1940, and the weather was absolutely beautiful, with long sunny days and star-lit nights. Nobody in this country really knew that bloody battles were raging between British and German troops in Belgium and France, just thirty or forty miles away across the English Channel. For my part, I’d been settled in Drake barrack block, and on the following day, at first light, I was woken up by a Royal Marine bugler sounding reveille, at some unearthly hour it seemed, but in fact it was 5a.m. I’d got dressed on the double, and with the rest of the jack tars in my block, we tumbled out of the barrack block like children tumbling out of school, on to the parade ground, where a chief petty officer was waiting with tolerable patience, for a Royal Navy petty officer that is, encouraging us to assemble with endearing words such as: ‘Come on you idle bastards, get fell in, you’re slower than a gay bridegroom getting ready for bed with your newly wedded lady bride,’ and other endearing comments that even you hard-nosed lot of sots shouldn’t be made privy to.

‘We’ve all been there and done that Jack, but what happened when you were assembled on the parade ground?’ he was asked.

‘Don’t be so damn impatient, I’m coming to that,’ he said, as he took a swig from his mug of tea before continuing his story:

When the chief petty officer had us standing to attention he strolled up and down our ranks a few times, prodding some of us in the belly and others in the arse with his swagger stick, just to let us know who was boss. He walked out to face the assembled parade before barking out: ‘If there is any seaman here who knows anything about the River Thames, step forward.’

Now I thought that order was a bit iffy, verging on the suspicious, especially because Chatham Royal Naval barracks is sited beside the River Medway, but he did say the River Thames, so I took a chance and stepped forward out of the line.

The petty officer walked up to me, looked me up and down, walked round me as though he’d never seen a specimen like me before, then, pushing his nose almost into my ear, ‘So, sailor boy! What do you think you know about the River Thames?’ he roared out like a bull elephant.

‘Everything,’ I replied in a loud clear voice, loud enough for all my shipmates on parade to hear.

Then the loud-mouthed sot burst out laughing, spraying me with spittle before he repeated, ‘Everything?’

‘Yes, everything,’ I replied. He was on my territory now.

‘So how does it come about that one of His Majesty’s jolly jack tars knows everything about the River Thames?’ he bellowed for the benefit of the assembled parade.

‘Because,’ I told him in as loud a voice as I could muster, without him being able to charge me with insolence, ‘I’m a Freeman-Waterman-Lighterman of the Thames.’

‘And what might that elongated title mean, sailor?’ he again bellowed in my ear.

‘Well, what it means is, if we were on a craft on the River Thames, either I or a river pilot, or some other Freeman-Waterman-Lighterman would have to be in charge of piloting the craft.’ I just left him with his own tiny biased mind to try working it out.

‘What?’ he yelled out. ‘You in command of ships?’ Then he scowled at me and said, ‘Wait here.’ He turned back to face the sailors and after a few ‘attentions’ and ‘at eases’ to relieve his pent-up frustration, he dismissed the parade. ‘Follow me,’ he growled. I did as I was bid, and he led me from the parade ground to the admiral’s administration offices.

It was not long before the chief petty officer and I were asked by a stern-faced but pretty-looking WREN petty officer to ‘follow me’. We were led into an inner office, where a tired-looking young man, white haired and old beyond his years, dressed in a first lieutenant’s uniform, was seated at a beautiful antique desk that had possibly been there since the naval barracks had been built, a couple of hundred years before.

‘Name and number?’ he asked in a voice as tired as he looked old.

‘Hicks, sir,’ I replied, and gave him my ratings number.

‘Know something about the River Thames, do you Hicks?’

‘I’m a Freeman-Waterman-Lighterman of the Thames, sir.’

‘A Freeman of the Thames! My God! What luck!’ he blurted out. ‘Then you’re just the man I’m looking for. I’ve got a job for you, Hicks. Wait outside.’

We saluted, the CPO and me, about-turned and marched out of the office and waited, in my case to find out what orders I was to be given. I didn’t have to wait long, just a few minutes. Then the WREN petty officer came out with a sealed envelope on which was written something like: ‘Sealed orders: To be opened only when on board LB13.’

There was also a second opened letter that gave me the substantive rank of acting petty officer and advised me in which port I would find my boat. It also gave me orders to the effect that ‘the boat’ was to be stored up ready for sea on my arrival at the designated port – dockets to draw stores were enclosed with travel warrants – and that I should give due diligence to speedily getting the boat round to the River Thames as quickly as possible. The orders also gave me the power to commandeer anything I may need to expedite my mission, and informed ‘Who or whomsoever this may concern’ Petty Officer (Acting) 34345 Hicks J. is in command of LB13 en route from Rosyth on the Firth of Forth to Tilbury Passenger Landing Stage on the River Thames.

After having read my orders, I passed the letter to the CPO, just to deflate that ignorant, arrogant, loud-mouthed, bullying bastard’s power-inflated ego. Then, having taken the letter from his hands which were trembling with rage, and to the WREN petty officer’s ‘good luck’, I made my way quickly back to Drake barrack block to collect my personal kit, before heading north to take command of my first Royal Navy boat, LB13.

I was stopped twice by crushers, Royal Naval Military Police patrols, on my walk from Chatham naval barracks to Rochester railway station, but I was quickly allowed to proceed on my way once I had shown the coxswains in charge of each patr...