- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

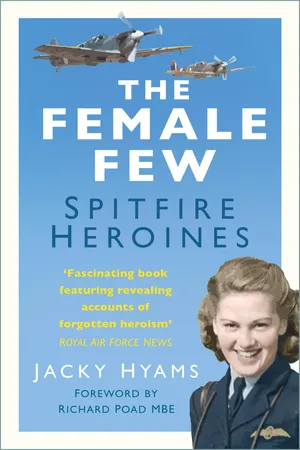

Through the darkest days of the Second World War, an elite group of courageous civilian women risked their lives as aerial courier pilots, flying Lancaster bombers, Spitfires and many other powerful war machines in thousands of perilous missions. The dangers these women faced were many: they flew unarmed, without radio and in some cases without instruments, in conditions where even unexpected cloud could mean disaster. In The Female Few, five of these astonishingly brave women tell their awe-inspiring tales of incredible risk, tenacity and sacrifice. Their spirit and fearlessness in the face of death still resonates down the years, and their accounts reveal a forgotten chapter in the history of the Second World War.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Female Few by Jacky Hyams in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Women in History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

A BRIEF HISTORY

In the 1920s and 1930s, the idea of taking to the skies was growing in popularity. Flying clubs had already started up in the 1920s, partially subsidised by the British Government. It was not until October 1938, when it was clear to some that war was imminent, that the Civil Air Guard scheme was devised, thanks to the efforts of Gerard D’Erlanger, a director of the then British Overseas Airways Corporation and an enthusiastic private pilot. The idea of this scheme was to encourage civilian would-be flyers. They might well be needed if war broke out. The scheme offered subsidised flying lessons at flying clubs. It was widely available to civilians, either sex, ages 18–50, who passed the private pilot’s ‘A’ licence medical.

The response to the news that the Government was contributing to flying lessons via the Civil Air Guard was overwhelming. Over 4000 would be flyers signed up. By May 1939, female members of the Civil Air Guard included approximately 200 pilots.

At that point, while the Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Air had told the House of Commons that in a national emergency, civilian women would certainly be used to ferry aircraft, it remained unclear where or how they would be deployed. Would it be via the ATS (the Women’s Army Auxiliary) or the WAAF (the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force)? No decision was made.

When war finally broke out at the beginning of September 1939 it was still unclear what kind of role, if any, the civilian women pilots would be playing. Yet the Air Transport Auxiliary or ATA was formed – thanks again to the resourceful efforts of Gerard d’Erlanger, founder and Commanding Officer of the ATA. He had foreseen a shortage of trained pilots if the qualified civilian group who could fly were excluded from joining the RAF. And it had been agreed that civilian women pilots could fly, so they could fly for the ATA.

Gerard D’Erlanger initially saw the ATA as a courier service, flying VIPs and wounded servicemen. But it quickly became obvious that the role of these civilian pilots would extend beyond that – and would involve ferrying aircraft from factory or maintenance to airfield so the RAF could then fly the planes into combat.

Letters had been sent out to about 1000 male pilots asking if they were interested in joining the ATA. After interviews and flight tests, 30 civilian men were chosen to fly for the ATA, qualified pilots who did not fit RAF eligibility criteria. Initially, the first group of male ATA pilots were seconded to work out of RAF ferry pools. It might have seemed obvious that any female ferry pilots recruited by the ATA could simply join them. But the RAF was not keen on the idea of women pilots, civilian or otherwise, at that point: war might have just broken out and all resources were needed. But women pilots? It didn’t seem likely.

If Gerard d’Erlanger was the driving force in the formation of the Civil Air Guard and the creation of the ATA, the individual who was largely responsible for the successful push to recruit women ferry pilots was the daughter of a well known Tory MP, Pauline Gower (see Appendix IV).

An experienced commercial pilot and a canny strategist, Gower had already made it known to the authorities that a women’s section of experienced flyers could be deployed as delivery pilots, to complement the group of early male ATA pilots.

The combined efforts of these two people in the history of the ATA’s female pilots cannot be underestimated. Certainly, both were well placed to influence events and put their case forward at the highest level (d’Erlanger was a member of a renowned banking family as well as an accomplished pilot). But most importantly, they were far-sighted enough to see that gender issues would be irrelevant at a time of national crisis: what mattered was that those civilians who were qualified to do the job as pilots were given the opportunity to do it.

On 23 September 1939, the Director of Civil Aviation Finance wrote to Gerard d’ Erlanger giving him authority to form a small women’s section of ATA qualified pilots. It would be separate from the men’s section. Pauline Gower would be in charge of it. Qualifications for women pilots would be exactly the same as those for men. In theory, at least, women pilots could be employed in the ATA.

But the plan to recruit women stalled in those early months of the ‘phony war’ mainly owing to the resistance of the RAF. It was politely suggested that perhaps the women pilots could take other war jobs? They could be useful. But no, they couldn’t fly with the Air Transport Auxiliary.

Yet events were moving fast. By November of that year, the picture was changing. It became apparent to the authorities that the ATA civilian flyer, either sex, had a key role to play. And Pauline Gower got her breakthrough agreement – an all women pool of women flyers could now be recruited to ferry small Tiger Moth training biplanes from the De Havilland factory at Hatfield, in Hertfordshire. Eight women pilots could be employed. More might be required by 1940.

Pauline Gower immediately got to work in December 1939. At 29, she was the newly appointed head of the women’s section of the ATA. She had held a commercial pilot’s licence for nine years, run her own aviation business and had completed over 2000 hours of flying time. Though in some instances, the experienced women pilots she was recruiting were older than her.

From her list of qualified women pilots, she invited a group of twelve to be flight tested at Whitchurch, near Bristol, on 16 December, taking them all out to lunch in Bristol before the test. Not everyone could be invited to join, so it was agreed that a few of the women would remain in their jobs. For the time being, at least.

The First Eight

Four months after war had been declared, eight women pilots joined the ATA on 1 January 1940. They were taken on as 2nd Officers. Their pay was set at £230 per annum, plus £8 a month flying pay (this was £80 per annum less than the earnings of a man on the same grade). The ATA male pilots were getting some assistance with their billeting (accommodation) expenses. Yet this did not apply to the women because they would be based at the Hatfield aerodrome to the north of London. They would be paying for their accommodation out of their own pocket. It definitely was nothing like equality. But thanks to Pauline Gower’s determined lobbying, the equal pay issue would eventually be remedied in 1943, the first instance in UK history of equal pay for equal work.

The ‘First Eight’ were Winifred Crossley, The Hon. Mrs Margaret Fairweather, Rosemary Rees, Marion Wilberforce, Margaret Cunnison, Gabrielle Patterson, Mona Friedlander and Joan Hughes. They were all qualified flying instructors with impressive experience in the air.

Winifred Crossley, a doctor’s daughter, had worked as a stunt pilot in an air circus. The Hon. Mrs Margaret Fairweather, had already worked as an instructor for the Civil Air Guard at Renfrew (her pilot husband Douglas had also signed up with the ATA). Mona Friedlander was, remarkably enough, an ice hockey international. Gabrielle Patterson, married with a young son, was the first woman in the country to work as a flying instructor; she had also been chief instructor and head of the women’s corps at the Civil Air Guard in Romford, Essex. Joan Hughes had started flying lessons at fifteen and became the country’s youngest girl flyer two years later. Rosemary Rees had completed a considerable amount of air touring. Marion Wilberforce was a pilot with her own Gypsy Moth. Margaret Cunnison was a flight instructor.

Out of this first group of pilots, Winifred Crossley, Joan Hughes, Marion Wilberforce, Rosemary Rees and Margot Gore (who would join the ATA a few months later and leave as a Commander) went on to complete nearly six years continuous ferrying for the ATA and remained with the organisation until it closed down when war ended.

The early women ATA pilots were mostly from wealthy backgrounds. But it is wrong to portray them as dilettantes, adrenalin junkies flying for kicks. Certainly, they had taken up flying pre- war because they or their families had the means to pay for lessons or even buy an aircraft – but they also flew because it was a hugely attractive proposition for the more adventurous, forward thinking type of 1930s woman: status alone did not satisfy their need for a challenge or excitement.

Much has been made, over time, of their social status, their depiction in glossy magazines, their upper crust partying in London hotels and nightclubs, their ‘It’ girl lives, in complete contrast to most of the country, struggling to cope with bombings, shortages, blackouts and wartime uncertainty. Certainly, in a superficial way, some of these upper crust flyers did bring a touch of much needed colour to the grim, grey perspective of war.

Diana Barnato Walker, millionaire’s daughter and debutante, who joined the ATA in 1941, is a good example of this type of fast living wealthy ATA flyer (see Appendix IV). But the upper crust or wealthy women were as committed and determined in their desire to ‘do their bit’ for their country as anyone else; as they would prove over time.

Yet the dawn of those early days in 1940 at Hatfield aerodrome could hardly be described as glamorous. The eight women all lived in billets in the Hatfield area and worked out of a small wooden hut on the airfield. It was a cold and muddy winter. There wasn’t much glamour in flying small, slow, training aircraft in freezing British weather in an open cockpit. Yet in this winter period they ferried over 2000 planes without any accidents. When you consider that many of the Tiger Moths being ferried from Hatfield were scheduled for storage in places like Kinloss and Lossiemouth in Scotland, ferry flights in those early years could also be an exhausting proposition.

The Hatfield pool could use three-seater Fox Moths to ‘taxi’ the pilots back from their short delivery trips to places like Kemble, in the Cotswolds or Lyneham in Wiltshire. But the only way back from a Scottish delivery flight was to take the night train south, often without a sleeping berth. Ferry pilots did not know where they would be flying to until the day itself, therefore there was virtually no chance of booking a sleeper. So the return trip from Scotland was often spent sitting upright in a crowded train that slowly crept its way south, through snowstorms and air raid alarms, often arriving in London many hours later than scheduled. Then, the woman pilot, laden down with her flying kit, would have to catch yet another slow train back to Hatfield, on occasion to report back to the ferry pool and discover she would be flying another plane up to the north of England.

The general public, of course, were completely unaware of what went on behind the scenes, although the opening of the Hatfield women’s pool had been accompanied by a blast of publicity. The war had only just started and the need to create a positive perspective on Britain’s air effort was important. So the ‘First Eight’ were photographed in flying gear and smart navy uniforms to be depicted in newspapers, newsreels and magazines everywhere. Pauline Gower was interviewed on the radio.

It certainly looked exciting and daring, this elite female group photographed scrambling to their Tiger Moths in their flying suits and fur lined leather flying boots. The image of goggles, flying helmet and sheepskin-lined Irvin jackets is instantly associated with the ATA female flyers but in fact, the jackets and leather boots were only ever issued to the First Eight and the goggles and helmet were required for open cockpit flying only.

The idea of bold women pilots doing war work usually seen as ‘a man’s job’ did not please everyone. Equality was still a long way off. ‘I am absolutely disgusted,’ one reader wrote to Aeroplane magazine. ‘When will the RAF realise that all the good work they are doing is being spoiled by this contemptible lot of women?’

Nor, alas, did the criticism come only from men. One letter, from a Betty Spurling, opined: ‘I think the whole affair of engaging women pilots to fly aeroplanes when there are so many men fully qualified to do the work is disgusting! The women … are only doing it more or less as a hobby and should be ashamed of themselves!’ One wonders what the comments were at the Hatfield aerodrome when the women learned they had stirred up so much controversy simply by wanting to fly and help the war effort.

By July 1940, the Battle of Britain was about to start: Britain was about to engage in the fight for her life, a fight conducted in the air. The women ferry pilots had toughed it out through the winter of 1940. They had proven their worth. So it was decided that the women’s pool at Hatfield should be expanded.

The First Year’s Expansion

In the summer of 1940, two more experienced women pilots joined the pool and one of them was a flyer known to millions: Amy Johnson, or Amy Mollison, her name as a divorcée.

Despite her world-wide fame and fabulous exploits, Amy Johnson came into the ATA like the rest of the women. She took her ATA flying test in a Tiger Moth. Tragically, she only would fly for the ATA for a matter of months (see Appendix III).

In June and July 1940 the intake of women pilots was increased. Ten more women were recruited, bringing the female contingent up to 20. Now they would be allowed to ferry all types of non-operational trainer aircraft, rather than just the Tiger Moths, so they could be ferrying the full output of the Hatfield de Havilland factory where the Tigers, Oxfords and Dominies were produced, as well as the Magisters and Masters then being produced at Woodley, near Reading, Berkshire, at Phillips and Powis (later known as Miles Aircraft). Further training on the twin-engined machines was given throughout that summer. The workload was on the increase.

Those early ATA days saw meagre ground resources: the women pilots would have to take it in turns to act as Operations Officer, collecting all the necessary information about the location of balloon barrages, prohibited areas of flying, weather reports from the nearest RAF Meteorological Office, all the crucial information the ferry pilots needed to fly safely.

At one stage, before a standard operations book was established, Pauline Gower would have to take down over the phone details of the planes to be ferried, scribbling them on a slip of paper. It was all very piecemeal. Yet the method of allocating jobs and attention to detail was meticulous, as it would remain throughout the war.

By the end of 1940, the ATA had expanded. Eight ferry pools were in operation all over the country; this would double by the end of the war. Central Ferry Control at Andover, Hants, was the hub of all ferrying operations, allocating all the work daily to each individual ferry pool.

At that point, the ATA employed 616 staff. 243 were ferry pilots and over 10 per cent of these were female: the number of women ferry pilots had now increased to 26.

Amongst the latest intake were Lettice Curtis, whose five years in ATA led to her delivering nearly 400 four-engined aircraft, 150 Mosquitos and flying over 50 different types of planes (see Appendix IV) and Margot Gore, who would later be Commanding Officer of the second all-women ferry pool at Hamble, near Southampton.

The Ferry Pilots Notes

Few civilian pilots joined ATA in the early days with any serious technical knowledge or experience of military aircraft. ‘A ferry pilot has so much to learn and remember that it is important that he is not taught one unnecessary fact.’ This was the sound philosophy around which ATA training revolved. As aircraft production increased as the war intensified, however, it became clear that ATA pilots were likely to be flying a variety of aircraft types. So handling notes were devised. Fi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- 1 A Brief History

- 2 Joy Lofthouse

- 3 Yvonne MacDonald

- 4 Molly Rose

- 5 Mary (Wilkins) Ellis

- 6 Margaret Frost

- Appendix I Ranks of the ATA

- Appendix II ATA Ferry Pilots and Flight Engineers

- Appendix III Five Lives Lost

- Appendix IV Famous Pilots of the ATA