- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A superb examination of the history of the Fens, containing a great deal of stunning photographs.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access From Punt to Plough by Rex Sly in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

‘City, Mead & Shore’

THE FENS

The counties of Lincolnshire, Cambridgeshire, Norfolk, and in a minor way Suffolk all lay claim to a part of the Fens. The Fens consist of fenland and marshland. Fenland is the land at some distance from the sea, which has been drained and protected from water from the highland rivers; marshland has been reclaimed from the sea. Since Roman times the landmass of the Fens has increased by one-third of its present-day size, thanks entirely to the ingenuity, hard work, and determination of mankind, to make up the largest plain in the British Isles, covering an area of nearly three-quarters of a million acres, which is roughly the size of the county of Surrey.

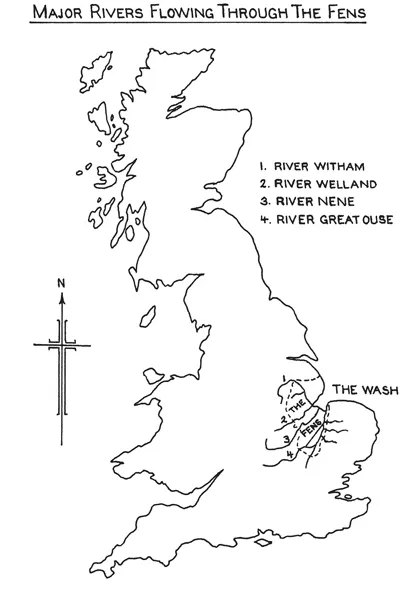

The rivers running through the Fens have a catchment area from the surrounding high country five times the size of the Fens themselves, making a total area of over 4 million acres to be drained. These rivers are all gravity fed through the Fens into the Wash and are almost all above the level of the land, some many feet higher. The fenland waters are pumped into the main drainage dykes and drains that traverse the Fens and from there they are pumped up into the rivers above or near the coast directly into the Wash itself. Many low-lying areas are pumped twice and some three times before being discharged into rivers. The total pumping capacity of all the pumping stations in the Fens is capable of moving in the region of 10 million gallons of water per minute when they are all in operation. Add this to the highland water passing through the Fens and this gives one some idea of the water that is discharged into the Wash at times of flood. This highlights the management and expertise needed to maintain the status quo created by run-off. For thousands of years this has happened but what has changed is surface run-off, the time difference between the water being deposited on the soil or man-made surface and passing into the drains and rivers, a man-made problem created by urbanisation and changing farming patterns.

An artist’s impression of a fen before drainage. (RS)

On his journey through the Fens Daniel Defoe (1660–1731) described this area as being ‘the soak of no less than thirteen counties’. The main rivers discharging their waters through the Fens are the Witham, Glen, Welland, Nene and the Great Ouse, all beginning their life in the surrounding uplands. There are other small rivers of no less importance, such as the Little Ouse, the Steeping, the Wissey, the Lark as well as smaller becks, lodes and eaus all adding to this soak. The Great Ouse is the longest of them all, over 150 miles in length, with its source not far from the Cotswolds, gathering water from five counties on its way to the Wash. Its catchment area is over 2,600 square miles, or 1.5 million acres in total. Both the rivers Nene and Witham have catchment areas of over 1.6 million acres each from which to gather water and carry it to the Wash. The River Welland rises under Studborough Hill, 3 miles south-west of Daventry, and is joined by many tributaries on its way to the Fens, with a catchment area of over 0.45 million acres.

For thousands of years these rivers have gathered their waters from the hills and gleaned the soils of its finest particles of earth to be deposited in the fenlands. Forests blended with peat and over time decomposed, leaving us with rich black peat soils. Since the Ice Age the rise in sea levels at different periods caused large areas to be covered with seawater, and the inhospitable North Sea has also enriched this land with marine estuarine muds gathered from around our shores. These natural phenomena have left a legacy of soils unique to the Fens, silts, clays and peats of many variations. And just as it was water, from the sea and the uplands, that endowed us with this legacy of precious soils, so, ironically, it would be water that was to become man’s greatest adversary in controlling them for his own exploits.

Valuable topsoil that mother nature has taken several thousand years to create can be destroyed by one man during his lifespan on earth. Nowhere is this more in evidence than in the Fens themselves. The complex drainage system we have in the Fens today has been created over a period of almost 1,500 years, and would require several volumes and maps to explain how it evolved. Indeed, many books have been written and will continue to be written on this subject, for the question of Fen drainage is a never-ending, ever-changing phenomenon fuelled by controversy.

BOG OAKS

One of the characteristic features and great wonders of this area are its bog oaks, found in the black peat soils bordering the southern edges of the Fens. The ancient forests that have left this legacy flourished from the Neolithic Age, and were made up largely of oak (80 per cent of the total), but also of elm, birch, Scots fir, yew, hazel, alder, willow and sallow. The bog oaks are now buried in the peat soils but appear on the surface occasionally like skeletons of prehistoric monsters from a bygone age, spirits from the past to remind us of what was once here. They are found mainly around Holme Fen, but have been uncovered along the northern fringes of the Fens as well, usually exposed during the course of deep cultivations or land drainage. When the ploughs catch them they are uncovered by mechanical means and carted out of the fields for disposal. Piles of oak, pine or yew of varying sizes can be seen by the roadsides or near farms where they are cut up for burning as domestic fuel, or sold as garden features. As the depth of the peat soil is decreasing so are the number of bog oaks; they, like the great meres, will one day be just another Fen legend, with only relics remaining in suburban garden ornaments. Some bog oaks have been recorded measuring 90 feet in length, with no branches below 70 feet and severed 3 feet above the base. Historians say that these oaks lay in a north-easterly direction and that the storm that destroyed them must have come from the south-west. The oaks in Holme Fen, however, lie in a south-westerly direction, suggesting that a violent storm from the north-east destroyed them. Most of the oaks have their stumps still on them while some have been broken off about 3 feet above the stumps, indicating that they were buried beneath peat before the storm.

Bog oaks at Holme Fen below the surface along a fen dyke after cleaning out. The deposits of estuarine mud can be seen between layers of upland deposits illustrating the climatic changes over a period of thousands of years. (RS)

The stumps of bog oaks are sold for garden features. (RS)

This bog oak would have been over 90 feet tall. (RS)

The trees that can be seen today protruding from the soil on the side of the dykes lying in a layer of estuarine muds with a layer of peat above and below illustrate three distinct climatic changes that occurred over long periods of our history. The dark layers were caused by fresh water from the high land surrounding the Fens, which deposited soils that brought a regeneration of trees, plants and shrubs. This was followed by a rise in sea levels that caused flooding and layers of estuarine mud to cover the decomposed vegetation. The third change occurred when the sea levels fell, causing the uplands to flood the Fens once again with fresh water, forming new deposits of soil. These unique features can only be seen in certain parts of the Fens, mainly in the south, east and west sections or other low-lying parts, which would be the last to be drained. Today we can see them as the areas of black peat soil, or what remains of them. The variation in distance of the catchment areas of each river and the differing rainfall in those areas would only affect the parts of the Fen those rivers flowed through. This caused some parts of the Fens to flood while other parts, perhaps only 20 miles apart, remained dry, illustrating the effect these catchment areas had, and still do have, on the Fens themselves. With only natural drainage in the Fens at that time deposits of soil particles would have accumulated quickly, causing a mammoth build-up. This is evident by the post indicating the wastage of peat in Holme Fen since 1852, almost 13 feet in fifty-two years. Bog oaks have been uncovered over many years in varying depths of peat as it has shrunk and wasted, which may indicate that no one storm destroyed them but several. One tree I measured is 42 feet long, 3 feet in diameter at the base and 2 feet where it has been sawn off, making it probably 80 to 100 feet in length. It is also worth noting that the first branches were 30 feet from the base and the condition of the tree was excellent. The trees must have been hundreds of years old before they died and had ideal growing conditions to achieve this size, and, being of such mammoth proportions, must have reached maturity before the peat formed because forests and peat do not go hand in hand. We cannot be precise about the age of these trees because even carbon dating techniques cannot reveal such significant detail, but evidence suggests that we are looking at a period of many thousands of years back in our history.

HISTORY OR MYTH?

Many of the early writings and maps relating to pre-sixteenth-century drainage were in the hands of the religious houses that proliferated in the Fens during the Middle Ages, but as many of these were plundered by the Danish invaders of the ninth century or were destroyed in the Reformation much of this early information has been lost. Fire was another hazard: Crowland Abbey had one of the most extensive libraries in the land, but in 1091 was destroyed by a great fire. It is this lack of written sources that has led many historians and writers to speculate on what degree of drainage and embankment was carried out during the late Roman and medieval periods in the Fens. As H.E. Hallam says in The New Lands of Elloe, ‘Few parts of England can have their history so grossly misrepresented as the Lincolnshire Fenland, ignorance and interest have combined to produce a hardy myth, which continues to perpetuate itself, even now, in the works of reputable authors.’ In part this ignorance has been due to the absence of major trunk roads and industrial urbanisation, which has left the fen soils undisturbed, except to the fenman’s plough, for hundreds if not thousands of years. This has preserved the past to some extent and kept historians and archaeologists in limbo. But we are now seeing major changes in the Fens, with mass house-building, increasing industrial expansion and a more extensive road programme, all of which could unearth many historical facts and quell the ‘hardy myths’. With almost all the Fens under intensive arable farming much of the surface evidence of our past has already been destroyed. Such progress is inevitable, but for some it will lessen the mystery of the Fens and its past. For my part I pray that the origins of the dykes and sea banks, the names of villages and places may never be disproved by modern science, to spoil our dreams and fables; for without these the Fens will never be the same. A life without mystery is like a sleep without dreams, refreshing but unenchanting.

THE EARLY YEARS

To understand the intricate network of drains, rivers and bridges, together with the pumps, sluices and slackers we have today, it is essential to look back in time at man’s achievements and failures. Evidence from all the major periods of human existence – from Bronze Age to Iron Age, from Romano-British to medieval – is to been seen in and around the Fens, denoting the importance of this land for settlement. At Maxey, on the north-west edge of the Fens, flint implements have been found and aerial photographs clearly show up the boundaries of a Neolithic settlement. At Flag Fen near Peterborough there is a Bronze Age settlement, discovered partly as a consequence of the construction of a new gas power station in 1982. Now one of the most important sites of this period in Europe, this was the first proof of Bronze Age human activity in the Fen, and was preserved under layers of peat in remarkable condition. In the past few years the extensive gravel extraction works between Peterborough and Thorney have revealed further evidence from this period, suggesting that agrarian practices were carried out here on a commercial scale rather than mere subsistence farming.

Wingland New Bank, 1910. Most pre-seventeenth-century drainage took the form of embanking, not drainage proper, as this photograph shows. (CC)

The Romans had several garrisons on the edge of the Fens and evidence has been found of settlements in the Fens themselves. In 2002, when the Weston bypass was being constructed, new evidence was unearthed of a Roman settlement at Weston, 2 miles east of Spalding. The coastline of the Wash recedes inland and has always been a natural receptacle for the tides. Wainfleet and Burnham in Norfolk were major Roman ports and with the many rivers running inland for long distances this must have made the Fens attractive for ships. We can assume that many of today’s inland towns and villages were also used as ports or staging posts for the transport of goods. Aerial photographs have also revealed the sites of other Roman (and medieval) settlements. At certain times of the year, especially when the fen soils are void of arable cropping, these pictures are perfect platforms for this panoramic x-ray of the past.

The Romans were attracted to the Fens because of the fertile soils and their products, such as fish, eels and waterfowl, but also because of the tradition of extracting salt from the sea along the tidal stretches of the Wash, which in Roman times would have been much further inland than it is today. There is considerable evidence of Iron Age and Romano-British salterns in several parts of the Fens, and new finds are still being unearthed to further our knowledge. Much has been written on this subject, especially by Heritage Trust of Lincolnshire and the Cambridge Unit, both of which have ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 ‘City, Mead & Shore’

- 2 ‘Brethren of the Water’

- 3 The Wash: The Fenman’s Last Challenge

- 4 ‘Water Loves its Own Way’

- 5 ‘Many Worlds More’

- Acknowledgements