![]()

Chapter 1

A TOUGH ‘JARRA’ LAD: FORGED FROM HARDSHIP

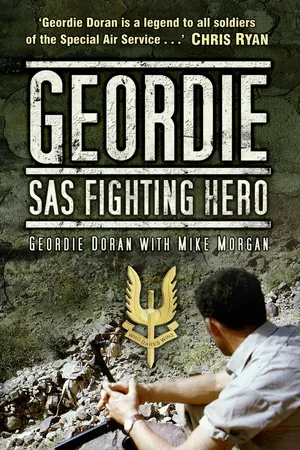

I believe it’s a fact that no one seems to know exactly where the term ‘Geordie’ has come from. But over the centuries it has become widely accepted that it refers to a person born on Tyneside – not just the city of Newcastle, but in any of the towns that lie along the banks of the River Tyne. This Geordie, as I became known in the SAS Regiment and later far and wide, was born in Jarrow, pronounced ‘Jarra’, in 1929, the year of the infamous Wall Street ‘stock market crash’. I was later confirmed in the Catholic faith in the full name of Francis William Joseph Doran, but have always been known to my family as Franky. However, the instant I joined the Army my comrades dubbed me Geordie – and the name has stuck to this day and is the one by which I will be referred to throughout this book.

The north-east of England, where I was born on 23 February of that fateful year of 1929, was to be devastated by worldwide economic depression. It bred poverty, crushing unemployment, desperation – and some of the toughest breed of survivors and fighters known to man.

I first saw the light of day, or rather the dim light of my parents’ bedroom, in their upstairs flat in Hope Street, Jarrow-upon-Tyne. Catherine Cookson, the late famous novelist, lived about 2 miles away at the time, and I have to admit that I later became an untypical, but avid, fan of her dramatic, romantic works.

The fifth of eight children, I had two brothers and five sisters, of whom only two sisters now survive.

Hope Street, like most other streets in Jarrow, was terraced. There were no front gardens – just a backyard, usually shared with another family, in which the toilet and water tap were situated. Pa, who was also called Francis, used to hang our tin bath on the wall out there as well. We didn’t have a bathroom; the accommodation was so small and cramped – two rooms – there was just no space for such luxuries. It was so crowded at times that whenever someone wanted to leave to visit the outside toilet, or ‘netty’ as we called it, everyone else had to stand up to let them out!

I was born a second-generation Englishman. In the 1880s my paternal grandfather travelled over from Ireland to find work in the Tyneside shipyards. Both he and his wife, whose maiden name was Quinn, came from Mayo Bridge, a small village in County Down on the slopes of the Mourne Mountains.

My mother, Dorothy, whose maiden name was Blythe, had Scottish ancestors. Her dad died before I was born, as did both my dad’s parents, so I knew only my maternal grandmother, also called Dorothy. I was 8 years old when my grandma died, and I missed her very badly. She was a lovely woman and had a large family, so I had lots of uncles, aunts and cousins.

Sunday afternoon was visiting time when Mother would take us little ones to see an aunt or two, but we would always end up at Grandma’s at tea-time. Grandma would always have a big, roaring fire going, with a huge, black cast-iron kettle on it to boil water for the tea. She would give us all a king-sized mug of char with some of her beautiful home-made scones to go with it.

My earliest memories are of dimly lit rooms in the house where we lived and of figures huddled around the fire. My parents often had to use candles for light when they couldn’t afford a penny for the gas.

The Wall Street stock market crash in New York caused an unprecedented worldwide depression of cataclysmic proportions. In Britain it generated a vicious slump which hit the north-east particularly badly, especially Jarrow, where there was only one main industry: building and repairing ships. Few ships could be built or repaired any more, because there wasn’t the cash or credit available to pay for them. What work there was went to the bigger yards further up the river, or to other parts of the country. Most of the men in Jarrow were consequently thrown out of work. My dad was a shipyard riveter, so he was also forced onto the dole queue and had to find casual work doing anything whenever and wherever he could. It was an increasingly hard existence, but my family was very close-knit and stuck together and made the best of it.

When I was about 3 years old the family moved to Stanley Street, a carbon copy of the salubrious surroundings of Hope Street.

One of my more dangerous games involved a fresh fish shop across the road. I used to love to run over, touch one of the fish, which were laid out in an open window, and then run back again as a dare. Crossing the street then wasn’t the hazard it is now: there was just the odd horse and cart or coal lorry. But I nearly copped it one day, though, when I ran out in front of the coal lorry and the driver managed to stop just inches from me!

Just before I was 5 years old we moved to Caledonian Road, which was near the centre of town. We occupied no. 33 at first, next door to Dad’s sister Annie in no. 31. Later on we moved into no. 31 after Aunt Annie and her family went south to Luton. Caledonian Road was exactly the same as the other streets, except the houses were mainly single-storey. There was a pub at one end of the street – The Cottage Inn – and Meggie Colwell’s little sweet shop at the other end.

We were desperately poor at this time, but even though we were dressed mainly in hand-me-downs and old shoes we never went seriously hungry. I remember having porridge nearly every morning. On Wednesdays we would have shepherd’s pie. Mother was a dab hand at making broth with just spare ribs. She used to make it in a massive black pot. You could smell it cooking half a mile away – everybody around knew when the Dorans were having broth for dinner! We used to get fat dripping from the butcher’s in a jam jar to spread on bread like butter, and it was delicious. Saturday was ‘pease pudding’ day. Mother used to send me to the pork butcher’s for a jug of pease pudding, which was always hot and liquid. The jug used to be so heavy that I had to carry it with both hands. I would quite often stop and have a sip – it was lovely. Our family always had a decent Sunday dinner of roast beef and Yorkshire pudding, with spuds and cabbage, followed by semolina or sago pudding. A big bag of broken biscuits (cost, one old penny) was a special treat. I don’t think I had a whole biscuit until 1953, when sweets were de-rationed eight years after the Second World War ended.

Every day at school all the children whose dads were on the dole or on very low income were entitled to free milk and a dinner. We had milk at school but had to go to the public baths for our dinner. They put boards over the pool, and the place became a dining hall. It was only used for swimming in the holidays.

Once a week the Salvation Army, which had a hall in the next street, would give out free loaves of bread to the needy. To qualify for that handout locals had to go into the hall, listen to some preaching and join in the hymn-singing. The hall didn’t have a lot of room inside, and so it paid to get in the queue early. There was always a crowd of ragged kids attending these sessions, usually including myself and one or two of my sisters. The Salvation Army staff, to their great credit, never asked any questions about which religion anyone belonged to. They simply handed out the bread regardless. As soon as the Dorans got their loaves we would run home and give them to our mother, who didn’t ask any questions either!

This tough regime of hardship and daily survival on the streets, living by our wits and luck, continued more or less unabated until the outbreak of the Second World War. I grew leaner, fitter, stronger and ever more streetwise, but never lost sight of the strong family values which became my permanent anchor throughout my adventurous life.

Money may have been extremely short at this time, but there were some things in Jarrow that the locals had more than enough of – and that included vermin of all kinds. Rats, mice, beetles and cockroaches were liberally distributed throughout the town – and some families specialised in extras, such as fleas and bed bugs! Most of the houses suffered from damp, as there were no damp-proof courses or cavity walls then. I recall that beetles and cockroaches thrived in such conditions, and the first one out of bed in the morning would hear their tiny feet scurrying away to hide. Mousetraps were essential pieces of equipment in every household. What made matters worse sometimes was that a lot of people used to stick wallpaper on with a mixture of flour and water. That was fine until the damp caused the wallpaper to peel and, usually through the night, drop off. Mice would then home in on it for a snack. The rats were not quite so numerous, but they were exceedingly bold. One day I was walking down our street when I spied a big rat squatting on its hind legs in the gutter. It was chewing on a lump of something which it held with its front paws. As I drew level it stopped chewing and looked right up at me. It seemed to be saying, ‘Who the hell are you, and what do you think you’re doing walking down my street?’ Even the rats were tougher than anyone else’s.

When I was 5 years old my mother asked me if I would like to stay at home or go to school. As I had a lively, enquiring mind, I readily chose school and started at St Bede’s Roman Catholic Infants’ School in Monkton Road, Jarrow. I can’t recall much about my time at that school. The priest would take confession and then give absolution and a penance – usually a few prayers which had to be said later. I can’t remember on that initial occasion having any sins to confess. I was only a nipper, when all was said and done. If I went back today it would be a very different story: the priest would need a secretary to write it all down and I would be excommunicated on the spot!

Our family was strict Roman Catholic. Besides going to Mass on Sundays and so on we had to say our prayers every night before going to bed. All of us children would kneel down and say our prayers together. Pa would usually be listening to make sure we said them correctly and didn’t miss anything out.

Religious fervour and young boys don’t mix very well, however; I was much more interested in going out to play with the other lads in our street. We were too busy climbing, fighting and playing games to worry about saving our little souls. No one could afford a football, so we played with old tin cans, each boy guarding his own back door and at the same time trying to score in another. Tin cans are dangerous missiles, and I’ve got a scar on my chin to this day to prove it.

Paper aeroplanes were another popular pastime. The type of paper used in the manufacture of an aeroplane is crucial to the quality and performance of the finished product. Pages from mail-order catalogues were the best: they were glossy, strong and stiff enough to hold their shape for long periods of active flying.

Another popular use to which catalogue pages were put in those days was as toilet paper. Hard and glossy they may have been, but they were free. Newspapers and proper toilet paper cost money. A good, big catalogue could last a family for a month or so, especially when economy was practised, whereby each page was torn into at least four pieces to make it go further.

I still remember the names of some of my back-lane playmates. There was Ginger Ambrose; Freddy McLellan; Reggie Jarvis, whose dad was killed in the Merchant Navy during the war; Philip McGee, whose cousin, with the same name as myself, Francis Doran, was killed at Dunkirk; ‘Tich’ Clinton; Tommy and Billy Henderson; and Franky Dixon and his brother Donald, who, until May 1997, was the Labour MP for Jarrow. All good lads and good friends. We all knew much poverty, hardship and grief in those days: poverty and hardship, because of the economic plight of Jarrow in the 1930s; grief, because so many of our pals, relations and family members suffered and died in the war or from illnesses and diseases, most of which are easily prevented or cured now.

Donald Dixon would probably be surprised to discover that, considering my background, I now vote Tory. I have gradually become disillusioned with the Labour Party, which most of my compatriots supported ardently.

As we grew older our back-lane gang ventured further afield. We would often play down by the Tyne ferry landing and downriver at Jarrow Slake, an old anchorage area mainly silted up by then but still with enough water in it to be attractive to children. Also there was always an area somewhere in town where old houses were being demolished and the occupants housed elsewhere by the local council – in the 1930s that was the start of council house estates. Those places, plus the old pit workings where there was a deep pond, were very dangerous to play around in and were often patrolled by the police. If the cops, or ‘slops’ as we used to call them, managed to catch us, we would get a kick up the arse or a good clip around the ear. Some of the cops used to put pebbles in the fingers of their gloves to make them heavier, and when you had a clout you really knew about it. It was no good going home to complain, because the chances were you would get another clout from Pa for getting into trouble. That made sense, because several children were drowned or injured in those workings. But kids will be kids, and we went and played there anyway.

Another area was the slag heap just outside town: a very large, flat-topped mound of leftover moulding material from the local metal foundry. It had been built up over the years until it covered an area of about 3 acres and was 60 or 70 feet high, perfect for playing cowboys and indians on! But our gang had to take great care if we trespassed on the territory of a local rival gang. Our street and the next one, Charles Street, had a long-standing feud with Ferry Street and Queen’s Road, and we had many pitched battles with sticks, stones and fists. In one memorable clash we used clothes props as lances. But even though the street gangs were all rough and ready and fought hard, they had a certain code of honour. We didn’t pick on girls or smaller children, and if there was a stone-throwing battle going on between gangs and some girls or little kids wanted to pass by, then both sides would hold their fire. If anyone failed to observe the temporary ceasefire, there would be a yell from one of the gang leaders: ‘Hey, stop hoying them bluddy bricks, there’s lasses and bairns trying ti get past, man!’ Also, if the police arrived on the scene and participants had to make a run for it, any member of any gang was always given fugitive status while hiding in an ‘enemy’ street from the common foe. I didn’t realise it at the time, but it was perfect preparation for the real war situations I was to be involved in many times during later years when my life, and that of many other comrades, was regularly to be placed on the line in hair-raising, real-life action. Meanwhile, as a growing, energetic youngster, this was fun and part of the early glimmerings of manhood. Gang warfare tactics and armament varied. I remember just before the war when Robin Hood, the film starring Errol Flynn, came to a cinema in Jarrow. All the kids went to see it, and within days we were all armed with home-made wooden swords and bows and arrows. Caledonian Road met Queen’s Road in mortal combat on an old building site. We fired arrows in the air and clashed swords. No one thought about throwing stones: it was all Robin Hood and the Sheriff of Nottingham doing battle. There were some casualties on both sides and a quantity of blood flowed, but nothing serious. I can’t remember which side won, but it was very exciting while it lasted! The Law arrived eventually and chased us all away.

I left the infants’ school aged 7 and attended St Bede’s Junior. By now I hated school and often played truant. On those days I would go for long walks, sometimes with a companion or two, but mostly on my own. My fellow truants and I would think nothing of walking 10 to 20 miles in a day. A favourite route would be to cross over on the Tyne ferry and walk on to the coast at Whitley Bay. We then had to pass through Cullercoats Bay en route where, if we had any money, we would buy a bag of winkles to eat. Whitley Bay was a popular seaside resort, with pebble and sand beaches and a funfair, but it has now seen better days. Of course as truants we never had any money for the funfair, but we always enjoyed ourselves on the beach. Another favourite walk would be south to Usworth aerodrome, 7 miles each way. We went there to watch the aircraft taking off and landing. It was pretty awesome. When the war started Usworth became an RAF training base. Also, after a couple of years the Americans came in on our side and established an anti-aircraft position there. It was great talking to the Yanks and cadging chewing gum from them. We sneaked into their kitchen one day and pinched some slices of ham. I had never tasted anything so delicious in my life before! We were always ravenously hungry on truant days, because we couldn’t go home until tea-time. I would be so hungry, I remember eating orange peel and bits of mouldy bread that I’d picked up from the ground – kissing it all up to God first, of course. I sometimes ate caramel toffee wrappers from the gutter, as I could taste the caramel on the paper. I even ate worms and slugs when there wasn’t anything else! To quench our thirst we would drink straight from streams or horse troughs.

I don’t know about now, but in the 1930s and up to the mid-50s, a lot of Tyneside housewives used to bake large, disc-shaped loaves of bread which were about 12 inches across by 2 inches thick and known locally as ‘stottie cakes’. (The name ‘stottie’ came about because if the bread went hard and was dropped on the ground it ‘stotted’ or bounced.) If it was a fine day when the stotties were first brought out of the oven, they would be put on an outside windowsill to cool. A backyard sill was favoured, away from roving dogs and hungry children; but now and then a few stotties could be seen on a front window. Several times I or my truant pals would snatch a stottie to satisfy our hunger. It was lovely bread, the like of which you don’t often get these days.

We learned a lot about hunger, thirst and fatigue on our truant trips. Years later, when I was in the Army, I suffered those three things many times. I think my days as a youngster doing our walks toughened me up and helped me to withstand it all. Also, playing in the muck and eating things off the ground probably gave us a certain amount of natural immunisation against some diseases. I’m sure it did.

Quite a lot of my school and back-lane friends did die from various illnesses, though. Tuberculosis, pneumonia, diphtheria and meningitis, to name but a few, were usually killers if contracted. Many children and young adults were crippled with poliomyelitis too. Rickets was mostly wiped out among the poor by the free issue from health clinics of malt and cod liver oil mixed in a bottle. Mother used to give us a big spoonful every day. Dried-milk food was also provided for children under 5 years. What with those health supplements, plus free dinners and milk at school, we were kept quite fit and well, although most of us were still fairly stunted in growth when compared with the children of today.

Family outings were a treat to look forward to. We had lots of trips to the seaside. The nearest sandy beach was at South Shields, a town at the mouth of the Tyne. From where we lived it was 4 miles to the beach, and the whole family, usually without Dad, because he’d be either busy in his allotment or working part-time somewhere, would set off walking early in the day to get a good spot on the beach. We had to walk, as the bus cost too much. Mother would be pushing a pram with my two younger sisters in it, plus a load of sandwiches, a teapot, brew kit and old jam jars to be used as cups. Just before reaching Tyne Dock, a town halfway to Shields, our party would trudge past the bottom end of Catherine Cookson’s street. (That street is long gone now; an industrial estate now occupies the site.) Once established on the beach Mother would organise the tea and sandwiches. Boiling water for tea could be had at several stalls at a penny a pot. After that it was ice cream cornets and maybe a ride on the fair as a special treat. The outbreak of the Second World War put an end to our family’s seaside jaunts, however. All beaches that the Germans could have used for an invasion were closed off and guarded, and most were mined as well. They were not open for public use again for almost six years.

Our family lived at 31 Caledonian Road until 1955. At first we had four rooms: two bedrooms, a living-room and a kitchen. The kitchen and the room above it had been built onto the original dwelling, and when my two eldest sisters went away to work in Luton the house seemed almost spacious. I used to sleep in the bedroom above the kitchen with my older brother, Matty. It wasn’t long, though, before that part of the house had to be demolished, a...