![]()

CHAPTER 1

Famine and Government Response, 1845–6

The great accident of nature that struck Ireland in 1845 was a raging epidemic of the fungal disease phytophthora infestans, commonly known as potato blight or potato murrain. Prior to the sudden advent of blight early in September of that year, there had of course been potato shortages, some of which were serious enough to be classed by contemporaries as failures. These shortages or failures were attributable either to bad weather or to plant diseases much less destructive than phytophthora infestans. In exceptionally wet years potatoes became waterlogged and rotted in the ground; in seasons of drought the lack of moisture stunted their growth. Before blight appeared in Ireland (or elsewhere in Europe), there were only two major plant diseases that attacked the potato periodically: one was a virus popularly known as ‘curl’, while the other was a fungus that non-scientists called ‘dry rot’ or ‘taint’.

Exactly when and how the new disease – a minute fungus of the genus botrytis – entered Europe are matters not surprisingly shrouded in some obscurity. Into these dark corners P.M.A. Bourke shed some valuable light.1 Almost certainly, potato blight was not present anywhere in Europe prior to 1842, and it probably did not gain entry until 1844. The source (or at least one source) of the infection may have been the northern Andes region of South America, particularly Peru, from which potatoes were carried to Europe on ships laden with guano, the seafowl excrement so much in demand as a fertiliser on British and continental European farms during the 1840s. An even likelier source of the deadly infection was the eastern United States, where blight largely destroyed the potato crops of 1843 and 1844. Vessels from Baltimore, Philadelphia, or New York could easily have brought diseased potatoes to European ports.

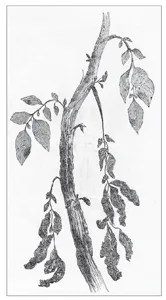

Once blight had been introduced from the new world into the old, its diffusion among the potatoes was extremely rapid, indeed even faster than the spread of the dreaded cholera among humans. This was essentially a function of the nature of the disease. The mould fungus that grew on the undersurface of blighted potato leaves consisted of multitudes of extremely fine, branching filaments, at the tips of which were spores. When mature, these spores broke away and, wafted by the air, settled on other plants, restarting the process of destruction. Rain was, like the wind, a vector of the disease, since water-borne spores from the leaves and haulms penetrated to the tubers below ground. The blight’s conquest of European potato fields was apparently the work of a single season or perhaps a little more. By the late summer and early autumn of 1845 it had spread throughout the greater part of northern and central Europe. The area of infection stretched from Switzerland to Scandinavia and southern Scotland, and from Poland to the west coast of Ireland. The ravages of the disease, however, were not the same everywhere. In regions stricken by blight early in the summer of 1845, crop losses were severe, whereas in areas not affected before mid-September, the damage was generally much less extensive, unless the harvest season was unusually wet. Thus Belgium, Holland, northern France, and southern England, all stricken by mid-August, were heavy sufferers, while Bavaria and Prussia among the German states, touched later and enjoying a dry harvest season, escaped with only slight damage. Ireland occupied an intermediate position in this spectrum of loss. On the one hand, blight did not make its first reported appearance until early in September, more than two months after the disease had originally been spotted near Courtrai in Belgium. On the other hand, much of the harvest season in Ireland was exceptionally wet, and the rains materially aided the progress of the disease.

Never before 1845 had Ireland, Britain, or continental Europe been visited by an epidemic of the fungal disease phytophthora infestans. Diseased potatoes from the northern Andes region of South America or from the eastern United States, carried by ship to Europe, were probably the source of the destructive fungus, which was endemic in the Andes and had very recently found its way to the east coast of America. This sketch of July 1847 shows the stem, or haulm, of a potato plant ravaged by blight. The fungus grew on the underside of blighted potato leaves and generated spores which, carried by wind and rain, promptly attacked the leaves, haulms, and tubers of other potato plants. (Illustrated London News)

For several reasons the early public reaction in Ireland to reports of blight was restrained. Everyone agreed that the oat crop had been unusually abundant – ‘the best crop, in quality and quantity, we have had for ten years past’, declared one northern observer at the end of September.2 It was also apparent that a larger acreage had been sown with potatoes in 1845 than in the previous year, and this increase was initially rated as considerable. Lastly, no reliable calculations of the deficiency could even begin to be made until after general digging of the ‘late’ crop commenced in the second and third weeks of October.

But the absence of alarm at the outset rapidly gave way to deepening gloom and even panic in the last ten weeks of the year. Day after day, letters testifying to the ravages of the blight poured in from anxious, frightened gentlemen and clergymen in the countryside, and general estimates of the destruction naturally swelled. The Mansion House Committee in Dublin, to which hundreds of such letters were directed from all over Ireland, claimed on 19 November to ‘have ascertained beyond the shadow of doubt that considerably more than one-third of the entire of the potato crop . . . has been already destroyed’.3 At the beginning of December the Freeman’s Journal asserted in an editorial that as much as ‘one-half of the potato crop has been already lost as human food’.4 What was so discouraging, and lent credibility to even the most despondent reports, was that potatoes which appeared sound and free of disease when dug became blighted soon after they had been pitted or housed. To many, it seemed that there was no stopping the rot. Typical of this despair was a Dublin market report at the end of October: ‘The general impression now is that with the greatest care the crop will be all out by the end of January, be prices what they may, as the tendency to decay, even in the best, is evident.’5

SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION

There was no shortage of putative remedies for staying the progress of the disease. As E.C. Large has remarked sardonically, ‘The potatoes were to be dried in lime or spread with salt; they were to be cut up in slices and desiccated in ovens; and cottagers were even to provide themselves with oil of vitriol, manganese oxide, and salt, and treat their potatoes with chlorine gas, which could be obtained by mixing these materials together.’6 The most prominent and widely publicised remedies were those offered by a scientific commission that Peel’s government appointed in October.7 Among its three members were Dr Lyon Playfair, an undistinguished chemist with good political connections, and Dr John Lindley, an accomplished botanist with both commercial experience and high academic standing (as professor of botany in University College, London), as well as the editor of the Gardener’s Chronicle and Agricultural Gazette. These two Englishmen were joined by Professor Robert Kane of Queen’s College, Cork, whose recent book on Irish industrial resources had attracted wide attention, and who already headed a subcommittee of the Royal Agricultural Improvement Society of Ireland that was investigating the blight.

The three commissioners had the triple task of recommending what should be done (a) to preserve seemingly healthy potatoes from infection; (b) to convert diseased potatoes to at least some useful purposes; and (c) to procure seed for the 1846 crop. In addressing the seed question, the commissioners could not ignore the fundamental issue of what had caused the blight in the first place. Here they went badly astray. Without pretending to certainty in the matter, they strongly inclined to the view that since the minute botrytis fungus must have existed as long as the potato itself, the root cause of the epidemic of blight was not the fungus but rather the cold, cloudy, and above all wet weather that had so visibly accompanied its progress. Without endorsing it, the commissioners did acknowledge the conflicting opinion of the Revd M.J. Berkeley, ‘a gentleman eminent above all other naturalists of the United Kingdom in his knowledge of the habits of fungi’, who believed that this particular fungus was itself the basic cause of the epidemic.8 Berkeley’s ‘fungal hypothesis’, though generally rejected when he elaborated it in 1846, was eventually proved correct. Yet even Berkeley admitted that wet weather greatly promoted the growth of fungi.

The commissioners therefore felt it safe to recommend that healthy potatoes from the blight-affected 1845 crop could be used for seed, since even if the germs of the disease were still present, they would be activated and spread only if the country had the great misfortune to be visited in 1846 by the same combination of bad weather that had prevailed in the current year. Any deficiency in home-grown sets of sound potato seed could be met, said the commissioners, by importing supplies from southern Europe (generally disease-free) on private commercial account. No active role as a direct purchaser was contemplated for the government.9 In this aspect of their work the commissioners greatly underestimated both the shortage of seed that would exist in 1846 and the difficulty of ensuring that no slightly diseased potatoes from the 1845 crop would be planted through accident or ignorance in the following year.

In an earlier report the commissioners had grappled with the other two main parts of their charge. What could usefully be done with blighted potatoes depended on the extent of the decay. Potatoes only slightly diseased – with up to a quarter-inch of discoloration – could be eaten by humans without risk, said the commissioners, provided that the diseased parts were cut away before the potatoes were boiled. No time should be lost in consuming such potatoes, they urged, because the advance of the rot would soon render them useless for food. But if the discoloration went deeper and the potatoes gave off a telltale stench, there was nothing to be done but to break them up into starch. Though not food by itself, the starch could be used to make a wholesome bread after being mixed with meal or flour.10 (Since the commissioners were concerned to maximise the amount of food that would be available for humans, they abstained from pointing out that diseased potatoes could also be fed to livestock, and farmers did this on a considerable scale.)11

What everyone wanted to know, however, was not so much what to do with potatoes going or gone bad, but how to keep good potatoes sound. Besides insisting that the bad potatoes should be segregated from the good, the commissioners’ basic message was that the crop must above all be kept dry. In place of the...